For 50 years, painter William T. Williams (NA 2017) has sought to expand the vocabulary of abstraction. In his fourth solo exhibition, simply titled William T. Williams: Recent Paintings, on view at Michael Rosenfeld Gallery in New York City through November 9, the 77-year-old sought to hold his audience’s attention through the refined use of color and texture. The 35 paintings from his 465 Series showcase the range of his palette, from muted hues to the highly saturated. Completed over the last three and half years, the mix of canvas and plywood pieces are also more diminutive than the expansive, geometric works he’s been known for in the past. “I wanted to make something smaller that was like a gem, and that the viewer could take more time looking at,” he explained.

Hung mostly in chronological order, Williams’s paintings reveal an aesthetic journey, as well as a personal one. His relocation from the city to Connecticut hailed a return to a rural lifestyle for the North Carolina-born artist. The move precipitated an increased attention to the use of color, particularly impacted by the ever-shifting natural light in his new studio. Six works completed in 2016 feature canvases organized into grids awash in earth tones, faded blues, and gentle greens. Instead of a single color being assigned to each block, as many as eight or nine coats of different colors sit atop one another, creating a dialogue between not only the blocks placed side by side, but also the layers themselves. From afar, it’s not immediately discernible if the fiery orange seeps out from beneath the narrow terrain of pale ochre, or if it’s applied onto the fissures in the otherwise subdued Water-Time, 2016. The result evokes the worn surfaces and cracked varnishes of old paintings seen in museums. Here, Williams replicates his own experience—a lifetime of gazing at works of art. His paintings reflect the passage of time and, in a larger sense, the “impermanent stuff” of life.

The one constant of his daily ritual, Williams listens devoutly to jazz music whenever he works. He begins every morning with Coleman Hawkins. He cites the “smoothness” of the saxophonist’s tone as inspiration. Certainly, there’s a deliberateness and delicacy in his playing that correlates nicely with Williams’s own technique. Throughout the day, he changes up the musicians depending on whether he’s starting or finishing a painting. Visitors to the gallery were treated to selections from Williams’s playlist, including songs by Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Jason Moran, and Wynton Marsalis. Further extending the genre comparison, Williams does not sketch before he paints. The process of dividing and subdividing the canvas, deciding on the colors and their edges, takes on an improvisational quality in that regard. One can almost read the rectangles and squares in a piece such as Blue Luck, 2017, like notes on a page. On the left side, shades of blue cut through a panel of mostly black; on the right side, a mosaic of red, yellow, orange, and green pops next to darker segments.

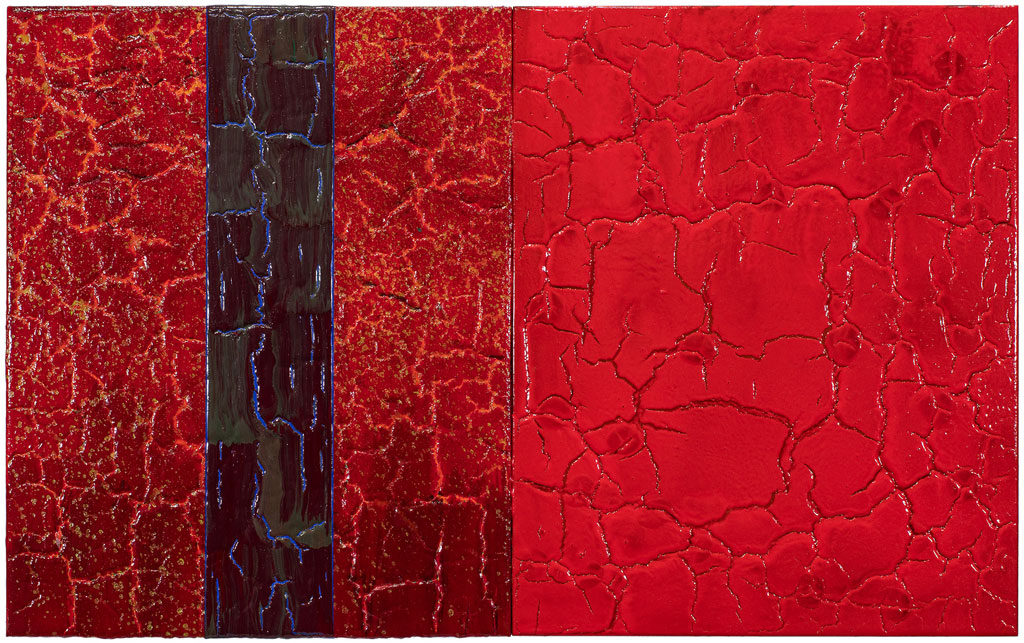

The work gradually falls into a noticeable rhythm, concerned with the repeated juxtaposition of contrasting colors. In July Doors, 2018, a stripe of black and blue vertically bisects the canvas like a warm summer’s night peeking out from behind two wheat-colored slats. Yet, Williams is quick to dispel any inclinations to decipher his paintings: “They’re not metaphors for anything. They’re not illustrations. I like things stripped down.” The simplicity allows the focus to remain on the saturation of color and the intricacy of surfaces. Williams realizes this vision with the intensity of red pigment that appears in Red’s Law, 2019, a piece named after his father who was known for his aphorisms. “He would say something like, ‘You have to take the hair with the hide,’” Williams reminisced. This penchant for philosophizing may be something the artist has inherited.

Above all, Williams said his work is about reaffirming life. As he’s gotten older, he sees the importance of slowing down to appreciate its fragile nature. Abstraction, then, becomes the method by which he’s able to produce a moment of immediacy, of being present, that forces viewers to confront what’s in front of them. He declared, “My job is complete when the viewer can stand in front of one of these paintings and there’s no separation between the painting and the viewer.”

William T. Williams: Recent Paintings is presented at Michael Rosenfeld Gallery in New York City September 6 – November 9, 2019.

Mimi Wong is the Editor-in-Chief of the literary magazine The Offing and New York desk editor for ArtAsiaPacific, the leading English-language periodical covering contemporary art from Asia, the Pacific, and the Middle East. Her work has also appeared in Catapult, Electric Literature, Hyperallergic, Literary Hub, and Refinery29. Born and raised in California’s Silicon Valley, she received her BA in English and American Literature from New York University. She is now based in Brooklyn.