I am a part of all that I have met;

— Alfred, Lord Tennyson, “Ulysses” (1842)

Yet all experience is an arch wherethro’

Gleams that untravell’d world whose margin fades

Forever and forever when I move.

Since most of the published responses to The Fulbright Triptych have been in the form of essays, rather personal ones at that, let me begin with a confession, as personal as the triptych itself by Simon Dinnerstein (ANA 1992; NA 1994). I am an art historian, chiefly involved with old masters, though I also have devoted time to modern Jewish artists. When I approach a work such as this imposing ensemble, my particular take must involve an art-historical reaction, tying its forms and content to precedents, starting with the triptych form itself and immediately racing on to the numerous inserted references. Then I must think about what kinds of paintings look like this, assuming that someone as historically informed as Dinnerstein draws upon an earlier class of pictures. But I also want to situate his work in the time when it was made: the early 1970s, in New York City, where he was born, raised, and trained.

Triptychs have a history, though they have been revived by modern artists. The three-part form, whose side panels (often hinged, like doors, for closing), took off during the 15th century, particularly for religious altarpieces in the Netherlands, and continued into the 17th century with the work of Peter Paul Rubens.1 Later, some tradition-conscious, early 20th-century German artists, led by Max Beckmann and Otto Dix, revived the form to produce complex counterpoints of secular social commentary.2

Completed in 1974, Simon Dinnerstein’s The Fulbright Triptych remains acutely conscious of its formal debt to the triptych heritage. Its crisp naturalism, particularly emphasized in its wing portraits, descends genealogically from the verisimilitude of oil paint technique developed by Jan van Eyck and his fellow Flemish artists. Indeed, the painting is full of homage to old masters of various lineages, avidly studied by Dinnerstein during his European travels, first on his 1970-71 Fulbright year in Germany—which reappears in the very title of the triptych—and amplified later from his base in Italy on an extended Rome Prize Fellowship (1976-79). Visual references abound across the three panels (another traditional Flemish painting method from before the rise of popularity of canvas during the heyday of 17th-century Dutch easel painting). They take the form of reproductions, whether cutouts or postcards, affixed to the background walls. For art historians, identifying Dinnerstein’s sources of visual inspiration is a form of nostalgia, recalling intense undergraduate study from photo archives on the eve of survey identification examinations.

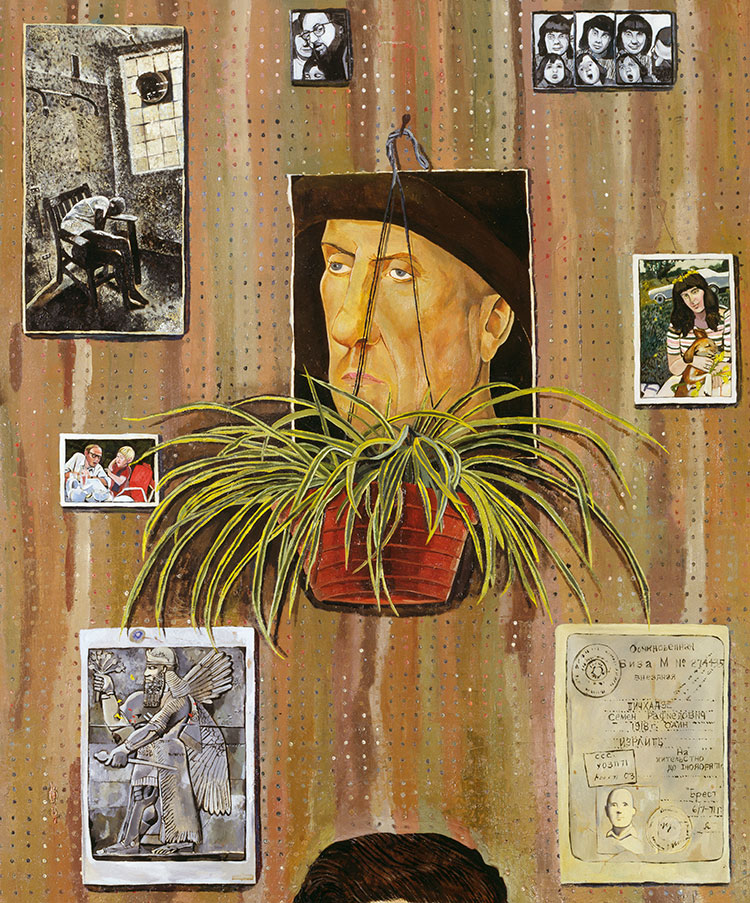

Van Eyck himself appears here. A detail from the 1432 Ghent Altarpiece, or Adoration of the Mystic Lamb, showing a half-length Eve with the “apple” (more like an etrog, which Dinnerstein will appreciate)3 appears just above the literal center of the triptych. In the right panel, directly above Simon’s own self-portrait (and hanging behind a planter), a super-close-up, colored detail of van Eyck’s c. 1435 Portrait of Baudouin de Lannoy focuses exclusively on the sitter’s features at three-quarter pose, cutting off his high hat (the same hat which provided Sir John Tenniel with the inspiration for his illustration of the Mad Hatter in Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, 1865).

Beside Simon’s right shoulder is a detail of the van Eyck mourners from his Crucifixion panel, a work that Dinnerstein did not have to go to Europe to experience in person in New York. And on the opposite panel, with the portraits of his wife, Renée Dinnerstein, and their baby, Simone, the color reproduction (at actual size) of van Eyck’s tiny Madonna in the Church echoes the mother and child of the present (and balances the photo of Donatello’s bronze Madonna and Child on the altar of Saint Anthony of Padua, c. 1448, above his left shoulder).

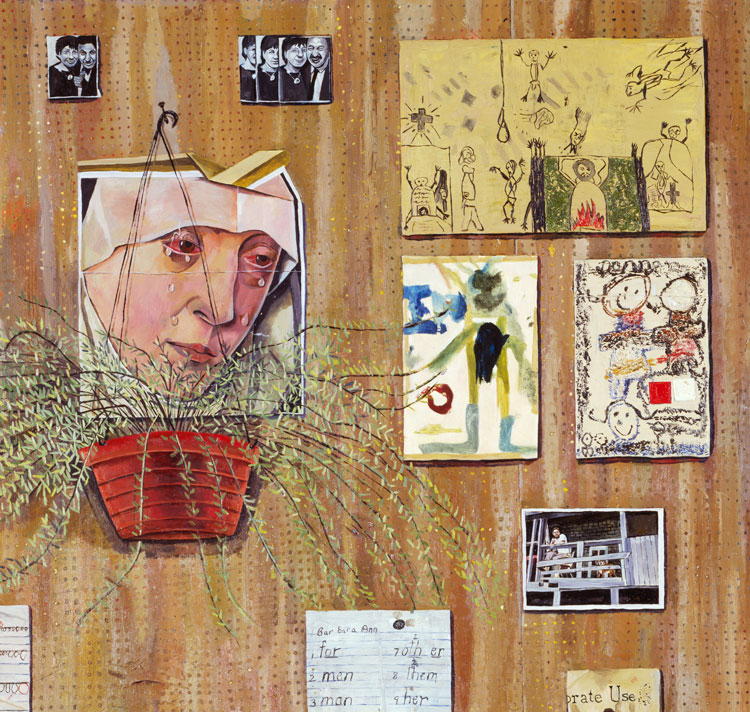

Directly over the head of Renée (and also behind a hanging potted plant) appears another extreme close-up of another work from Flanders in the later 15th century, this time a color detail of a weeping Madonna by Dieric Bouts from his diptych of the Mater Dolorosa, paired with Christ as Man of Sorrows.4 Other works by 15th-century old masters appear, such as the color reproduction of Jean Fouquet’s portrait of King Charles VII of France.5

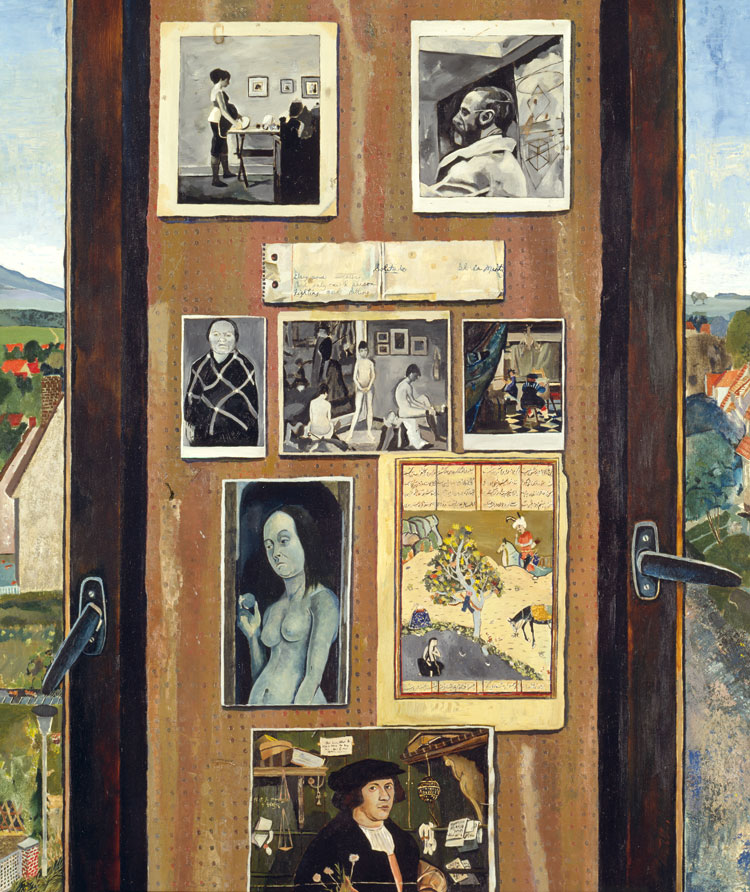

It might be tedious to itemize all of the references in The Fulbright Triptych, and of course there are many other images besides famous museum pieces on that painted back wall. But it is worth noting some remaining works that stand out. In the larger center panel in particular, one sees, reading from top left and then down: Giovanni Bellini’s St. Francis in the Desert, c. 1476–78; Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s Comtesse d’Haussonville, 1845; Hans Holbein’s chalk drawing of Jacob Meyer, c. 1525–26; and at bottom, a Georges Seurat drawing, Woman Reading.

Reading from the top center: another expansive Giovanni Bellini landscape, Holy Allegory, c. 1490 – 1500; Georges Seurat’s Models, 1886-88 in black and white; Johannes Vermeer’s The Art of Painting, 1666/68; a 16th-century Persian miniature (another miniature appears below Jacob Meyer); and at bottom center Holbein’s glorious portrait The Merchant Georg Gisze, 1532.

Reading down from the top right of the central panel, we find an unusual Holbein portrait drawing of a syphilitic man, 1523. Below it, a lamentation, La Pietà de Villeneuve-lès-Avignon, c. 1455, now attributed to Enguerrand Quarton; then Rogier van der Weyden’s Portrait of a Young Woman with a Winged Bonnet, c. 1440; and an Edgar Degas pastel, After the Bath, Woman Drying her Left Foot, 1886 (another Degas painting, A Woman Seated beside a Vase of Flowers, 1865—again familiar to Simon from New York—in a small color reproduction occupies the space above the Donatello Madonna and Child bronze in Dinnerstein’s own portrait panel).

Finally, in the right column are a Seurat graphic in Conté crayon of his mother doing needlework; and a close-up of the face and bald head of Donatello’s marble Florence Cathedral prophet, Habbakuk, popularly known as Zuccone (Pumpkin) 1423-25.

These references certainly form a challenging test of art history, but they also suggest Dinnerstein’s wide-ranging visual curiosity and search for models. When we look over these pin-ups for what they might tell us about his aspirations or inspirations in the early 1970s, we discern some patterns. Many of these images are portraits to begin with, made by some of the greatest painters of that genre: van Eyck and Holbein in particular, but also Ingres. Moving religious art, particularly imagery of Madonna and Child or mourners over Christ, also seem to have stimulated the artist. Since much of the art, whether portraiture or religious painting, is really early oil paint technique, it provides the inspiration for the verisimilitude and powerful presence of Dinnerstein’s own work. Landscapes also figure here, whether the Persian miniatures, the two inhabited works by Bellini, or even the two large, unidentified town studies. These latter seem to be based on actual German locations, perhaps experienced personally and studied by Dinnerstein during his Fulbright year, and they turn out (artist’s feedback) to be the actual view out the windows of the couple’s apartment in Germany.6

Can we surmise that these are his own landscape paintings-within-the-painting? And we certainly see the importance of the direct experience of all these works of art, particularly those that were long accessible to him in his native New York at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Frick Collection, or else within reasonable travel excursions from a German base during his precious year abroad (Vienna, Basel, Paris, London, even Florence).

Additionally, surrounding Dinnerstein are selected works of ancient Near Eastern art in prominent black and white insertions, including a frontal Sumerian priest (probably the one from New York’s Metropolitan Museum, surely familiar to Dinnerstein) as well as the Neo-Assyrian profile relief of a winged guardian figure (from palace decorations of Ashurnasirpal at Kalhu, modern Nimrud, 883-859 BCE; also preserved in New York’s Metropolitan Museum). Renée’s panel also shows an unidentifiable ancient or “primitive” artwork, perhaps to be understood as some kind of fertility figure, certainly one redolent of female sexuality.

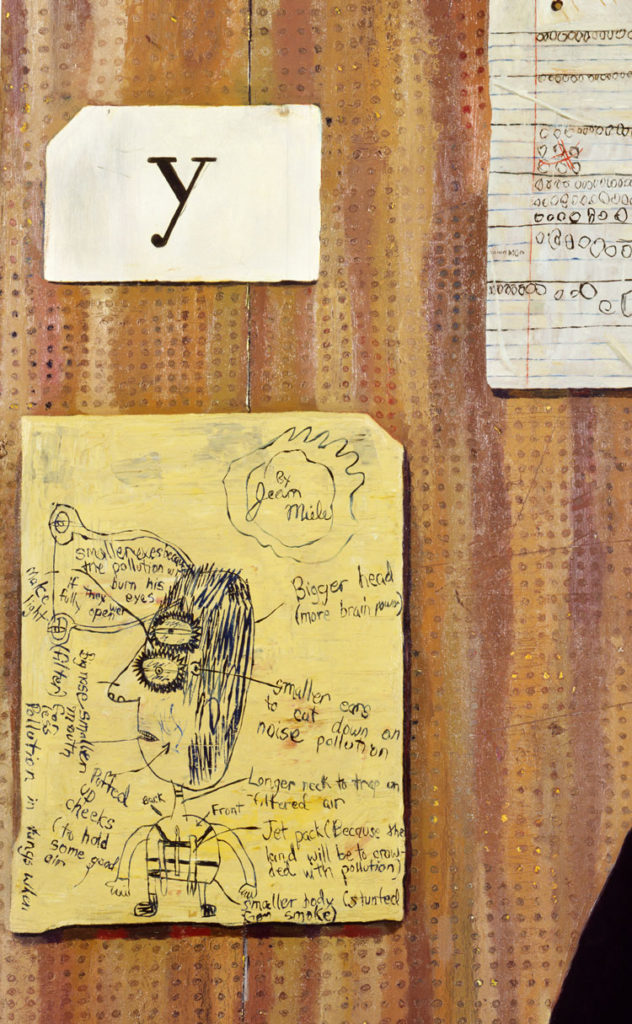

Of course, the triptych is loaded with personal items, known only to insiders, not to museum nerds like me. These include children’s drawings (by the artist as a young man? à la James Joyce?), which according to the painter, relate to Renée’s work as a teacher of young children. But of course, such works are the wellspring of all art, and have proved to be inspiring to numerous 20th-century artists.7

Also in the triptych numerous photographs appear, surely most of them referring to a younger (beardless but mustachioed) Dinnerstein, to Renée, and to family members of the previous generation for each of them—made all the more significant due to the presence of baby Simone in the left wing panel. As the Hebrew has it, l’dor va’dor (from generation to generation). Of course, all these images evoke the passage of time by freezing earlier moments, including subway photo booth images of the younger couple in the Renée wing, and even the two of them with young Simone (whose very name merges those of her two parents). Additionally, more recent publications that involve The Fulbright Triptych include images of an older Dinnerstein (now with a white beard) before his work, even with his larger current family, including Simone’s husband and son.8 The moment of his German work is inscribed, almost literally, in the printmaker’s tools, principally for engraving, which occupy the prominent, central table; however, among them, at the crucial intersection of the tabletop with the back wall, with its accumulated images from the past, is a stopwatch which not only records fleeting microseconds but is itself stopped in the painting.

Those reactions come from the picture itself and some awareness of its nod to past imagery and forms. It is worth noting, in passing, that Dinnerstein has violated one frequent (if not invariable) convention of pendant portraits of couples. He has placed himself in the right panel and Renée and Simone in the left panel. Yet according to heraldic precedence, as well as to the dominance of righthandedness in the vast majority of humans, the artistic convention is to place the husband on the viewer left (i.e. the right side from inside the painting) and the wife on the viewer right. The same phenomenon dominates Last Judgment pictures, where the blessing right hand of Christ from inside the work will appear at the viewer left.9 This is just as obvious in the donor panels of traditional triptychs, such as the Portinari Altarpiece by Hugo van der Goes, which was surely known to Simon from his visit to the Uffizi Gallery in Florence during his European year.10 So in this triptych, Simon has ceded precedence—against the grain of tradition—to his wife and daughter.

Another observation that one can make in relation to art-historical tradition is to invoke other paintings, largely from 17th-century Netherlands, that use collections of items, like Dinnerstein’s pin-ups, to convey the character of an individual. At the most mundane level, like the letter above the tabletop, they can consist of what are called letter racks, usually shown, as here, against a painted flat background. Dutch painters after the middle of the 17th century often used such letter racks to produce a version of trompe l’oeil pictures, deceptive illusions of reality in paint.11 Of course, Dinnerstein’s picture has many other things beyond a letter rack, but his own meticulous work and suggestion of illusion against a flat background surely grow out of that Dutch tradition.

From the same century, but on the Flemish side of the border that then separated the Netherlands was another tradition: the gallery painting.12 For that kind of image, a collector had his pictures painted as if on display in a single room; often the individual himself, such as a Habsburg prince or an urban patrician, would have himself and selected guests portrayed within the space, identifying him as both a distinguished and tasteful collector.13 While Simon Dinnerstein does not portray himself as owning the originals of those reproductions behind him, he does certainly claim to have absorbed them into his own visual thinking, and he suggests that his own art derives in dialogue with such inspirations.

Finally, where does Dinnerstein’s own art impulse come from, particularly the urge to paint with such compelling verisimilitude, as well as to invoke the influence of past masters and great artistic models? For me, the most obvious touchstone at the crucial moment of the creation of The Fulbright Triptych is the illusionistic work, dubbed at the time “photorealism,” of his New York contemporaries. In particular, I see a close parallel in the work of Audrey Flack.14Already in the 1960s, Flack used photographs as the inspiration for her own large-scale paintings, and her Vanitas series, 1976-78, while painted shortly after The Fulbright Triptych, provides striking analogies to it, including individual art references as well as associations with ephemerality or frozen time. For example, Leonardo’s Lady, 1975, shows a reproduction from an Italian monograph about Leonardo da Vinci’s portraits along with a pocket watch, as well as other time-bound items: female cosmetics, flowers, and fruit. In Queen, 1975, her mixed items include personal portraits of the artist herself and her mother in a locket, as well as more cosmetics, fruit, flowers, a watch, and the eponymous playing card and chess piece. Self-awareness and identity, personally inflected with Flack’s distinctive feminist consciousness. Another comparison, but much more focused on just an individual face in extreme close-up, is the large, early portrait paintings by Chuck Close (ANA 1990; NA 1992), including self-portraits as well as those of fellow artists and friends.

Thus, The Fulbright Triptych is a product of its moment (despite the prevailing attention to abstraction in contemporary criticism) as well as an outgrowth of much art historical tradition. Its self-consciousness and self-representation are indeed personal and unique, but at the same time deeply immersed in tradition, even while so richly and variously marking its own place in time.

Simon Dinnerstein: The Fulbright Triptych is presented at the McMullen Museum of Art in Boston September 9 – December 8.

Larry Silver is the Farquhar Professor of Art History, emeritus, at the University of Pennsylvania. A former President of the College Art Association, he has previously taught at the University of California, Berkeley and Northwestern University.

A specialist in early modern Northern European paintings and prints, he has organized print and map exhibitions and published monographs on Albrecht Dürer, Quentin Massys, Hieronymus Bosch, Pieter Bruegel, Peter Paul Rubens, and Rembrandt van Rijn, most recently Rembrandt’s Holland (2018).

He also has published about modern Jewish art, including (with Samantha Baskind) Jewish Art: A Modern History (2011).

- Here the scholarship by Lynn Jacobs is fundamental. See her Opening Doors: The Early Netherlandish Triptych Reinterpreted (University Park, PA; 2012). See also her brilliant insight that certain triptychs mirror the actual shape of a Gothic church interior, whose side aisles together equal the width of the central nave. Jacobs, “The Inverted ‘T’-Shape in Early Netherlandish Altarpieces: Studies in the Relationship between Painting and Sculpture, “Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 57 (1991), pp. 33-65. See also the interview dialogue between Dinnerstein and Jacobs in Alex Barker, ed., The Lasting World: Simon Dinnerstein and the Fulbright Triptych (Columbia, MO; 2017), pp. 29-46.

- See especially, Charles Kessler, Max Beckmann’s Triptychs (Cambridge, MA; 1970); Reinhard Spieler, Max Beckmann. Bildwelt und Weltbild in den Triptychen Max Beckmanns (Cologne, 1998); also more generally, Hans Belting, Max Beckmann: Tradition as a Problem in Modern Art (New York, 1989). For Dix’s great anti-war Dresden War triptych, 1929-32, Birgit Dalbajewa, Otto Dix: Der Krieg—das Dresdner Triptych (Dresden, 2014).

- James Snyder, “Jan van Eyck and Adam’s Apple,” Art Bulletin 58 (1976), pp. 511-515.

- See two versions in the opposite direction by Dieric’s son Albrecht Bouts in John Hand et al., eds., Prayers and Portraits: Unfolding the Netherlandish Dipytch, exh. cat. (Washington, 2006), pp.40-55, nos. 3-4; for two copies of the van Eyck Berlin Madonna in the Church, ibid., pp. 100-03, no. 13; pp. 140-49, no. 21.

- Erik Inglis, Jean Fouquet and the Invention of France (New Haven, 2011), pp. 108-122.

- Because I wanted to come to The Fulbright Triptych without a decoder ring, I tracked these pictorial references on my own, but Simon has provided a key himself in an earlier publication: Daniel Slager, ed., The Suspension of Time (Minneapolis, 2011), pp. 288-91.

- Jonathan Fineberg, Discovering Child Art: Essays on Childhood, Primitivism, and Modernism (Princeton, 1998); also Fineberg, The Innocent Eye: Children’s Art and the Modern Artist (Princeton, 1997).

- Slager, Suspension of Time, p. 214.

- James Hall, The Sinister Side. A Lost Key to Western Art (Oxford, 2008).

- Jacobs, Opening Doors, 143-47.

- Sibylle Ebert-Schifferer et al., eds., Deceptions and Illusions. Five Centuries of Trompe l’Oeil Painting, exh. cat. (Washington, 2002), pp. 188-95, nos. 35-38. The leading artists of this kind of pictorial deception were Cornelis Gijsbrechts, Samuel van Hoogstraten, and, especially, Edward Collier, about whom see also Dror Wahrman, Mr. Collier’s Letter Racks (Oxford, 2012).

- Victor Stoichita, The Self-Aware Image (Cambridge, 1997), esp. pp, 83-88, 103-47; Zirka Zaremba Filipczak, Picturing Art in Antwerp 1550-1700 (Princeton, 1987), 58-73; S. Speth-Holterhoff, Les peintres flamands de Cabinets d’Amateurs au XVIIe siècle (Brussels, 1957).

- Julius Held, “Artis Pictoriae Amator: An Antwerp Art Patron and His Collection,” in Anne Lowenthal et al., eds., Rubens and his Circle. Studies by Julius Held (Princeton, 1982), pp. 35-64.

- Thalia Gouma Peterson, ed., Breaking the Rules. Audrey Flack, A Retrospective 1950-1990, exh. cat. (Louisville, 1992); Audrey Flack on Painting (New York, 1985).