Peter Williams: Black Universe, a three-part exhibition curated by Larry Ossei-Mensah and Rebecca Mazzei featuring abstract and figurative works by painter Peter Williams (NA 2018), is on display at the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit and Trinosophes through January 10. A concurrent exhibition was presented earlier this year at Luis De Jesus Los Angeles. Understanding the impact of both the presence and absence of the body, Williams pushes the boundaries of this dichotomy to shed light on the interconnectivity of personal and historical experience. Williams’s 2019-20 Black Exodus series, prominently featured in Black Universe, draws on art history, popular culture, and Afrofuturism to tell the story of a group of African Americans who leave Earth due to environmental disaster. Narration and Transition, 2012-19, a survey of abstract painting on view at Trinosophes, reveals what Williams calls his “underpainting”—the visual and ideological foundations of his work. This oscillation between fixed and fluid signifiers reveals Williams’s search for a porous kind of truth, susceptible to the mirroring of past and present events.

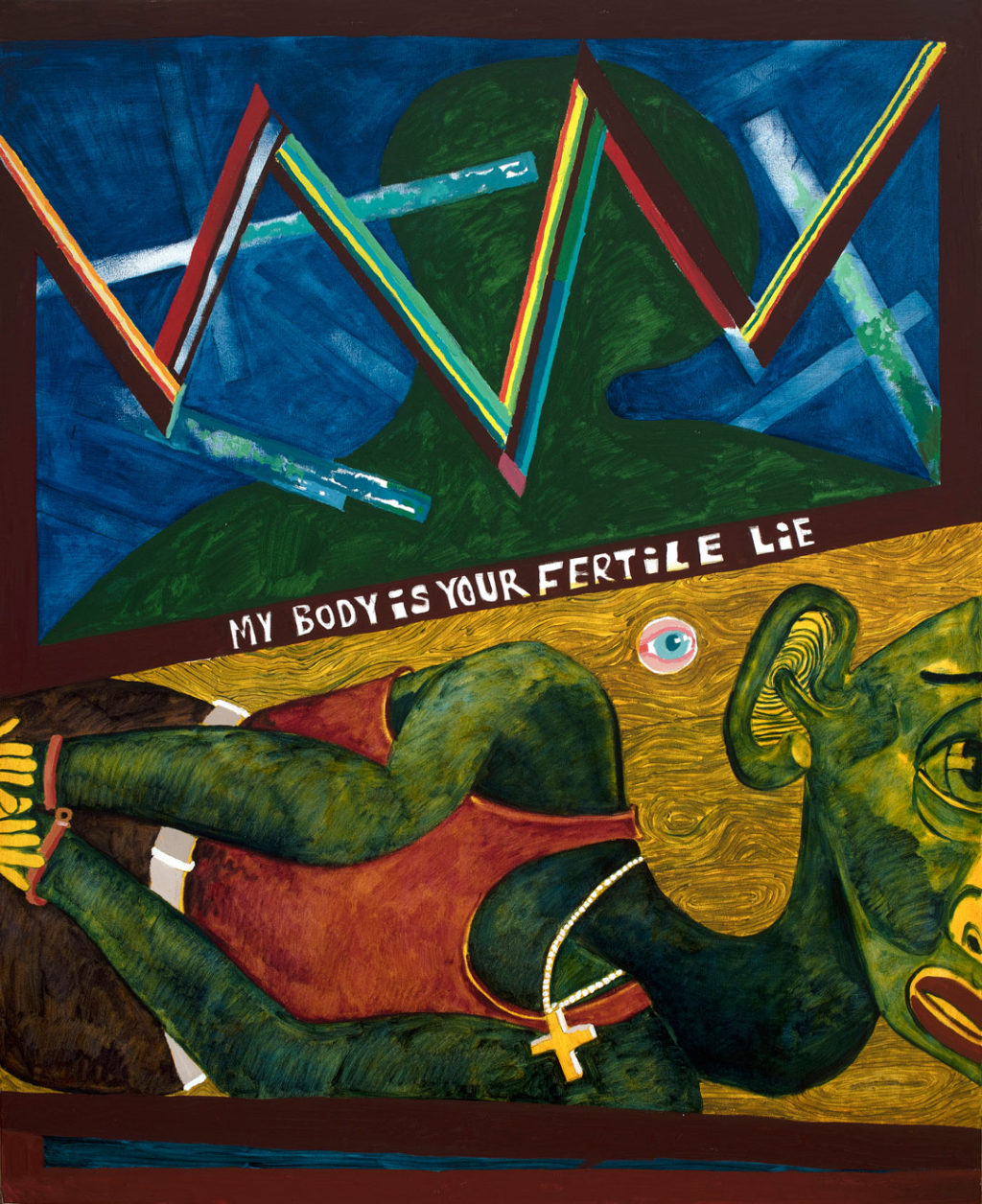

For Williams, the transition from abstract to figurative art is part of an equation towards meaning. In an interview with John Yau hosted by UNTITLED, ART,1 Williams described his abstract works as a “pre-vocabulary,” learning from the pieces’ obscurity to scope out his figurative and literal codes. Yet what may be ideologically opaque is vibrant on the canvas. Williams’s lack of allegiance to figurative form allows his talent for innuendo and allusion to shine through. Pieces like Pussy Galore, 2013, are formally attractive and funny—slopes of tangerine, chartreuse, and rose coalesce to form what may or may not be a vagina. Raking in other pop culture citations, such as the Roots song of the same name, Williams volleys reference points not only with his audience but with other culture makers as well. This willingness to let the audience in on his creative process exemplifies Williams’s commitment to accessibility—to artworks that are, as he puts it, “wholly graspable.”

“I can only learn about myself through dialogue,” Williams maintained in his UNTITLED, ART interview. He extracts color and meaning from the everyday to facilitate these dialogues with the viewer about “the history of our cultures and how we deal with each other.” Williams draws from color palettes that speak to their cultural contexts, pulling from the innovative use of hue and light found in Afro-Caribbean and other Black diasporic communities. In a 2017 interview with the Delaware Art Museum,2 Williams articulated his inspiration from roadside memorials—mini-altars comprised of objects such as handmade cards, lime-green teddy bears, yellow daisies, and red roses. The eye-popping color purposefully draws both the attention and empathy of the viewer, as much a plea to recognize the context of the death as its memorialization. It is this same guiding principal, the interplay between context and content, that drives paintings such as George Floyd Triptych, 2020, a three-part rendering of the life, death, and burial of George Floyd reminiscent of a stained glass window. Floyd’s death at the hands of four Minneapolis police officers sparked the ongoing Black Lives Matter demonstrations.

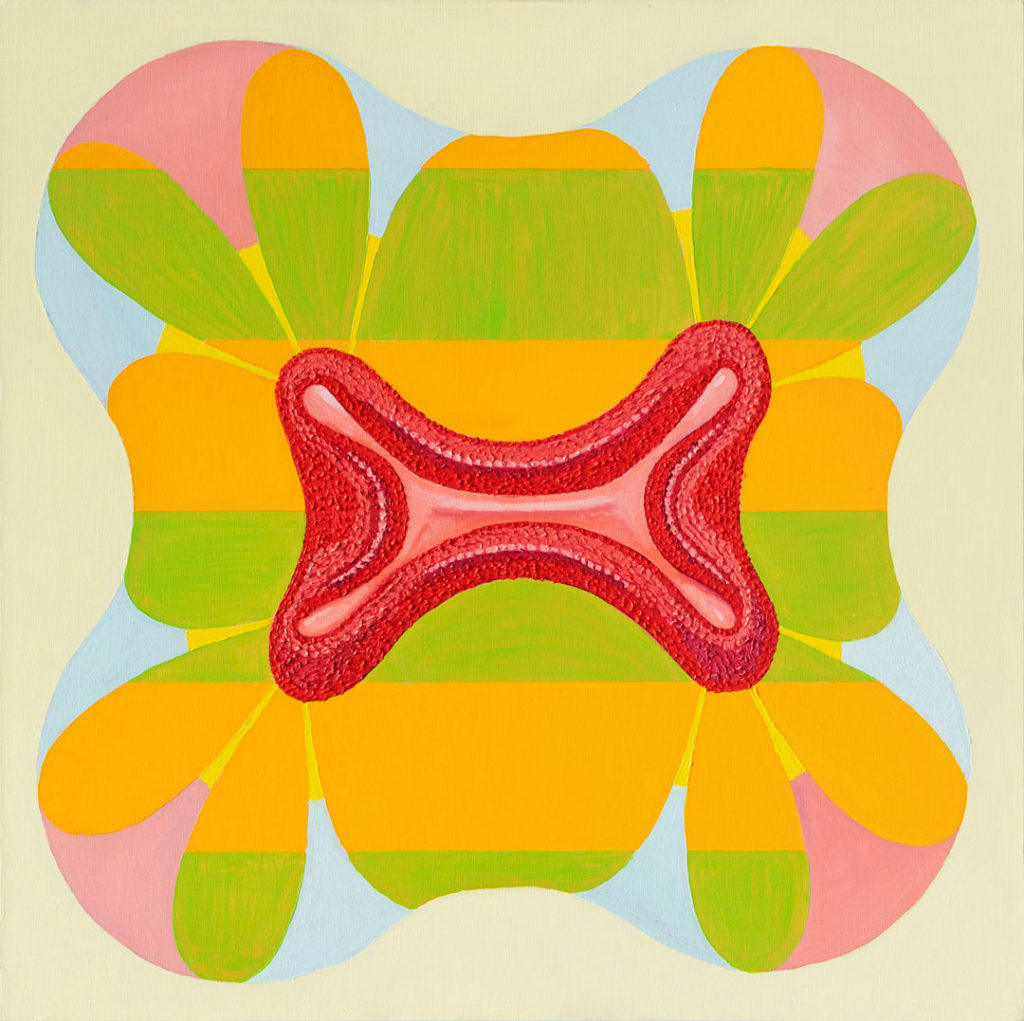

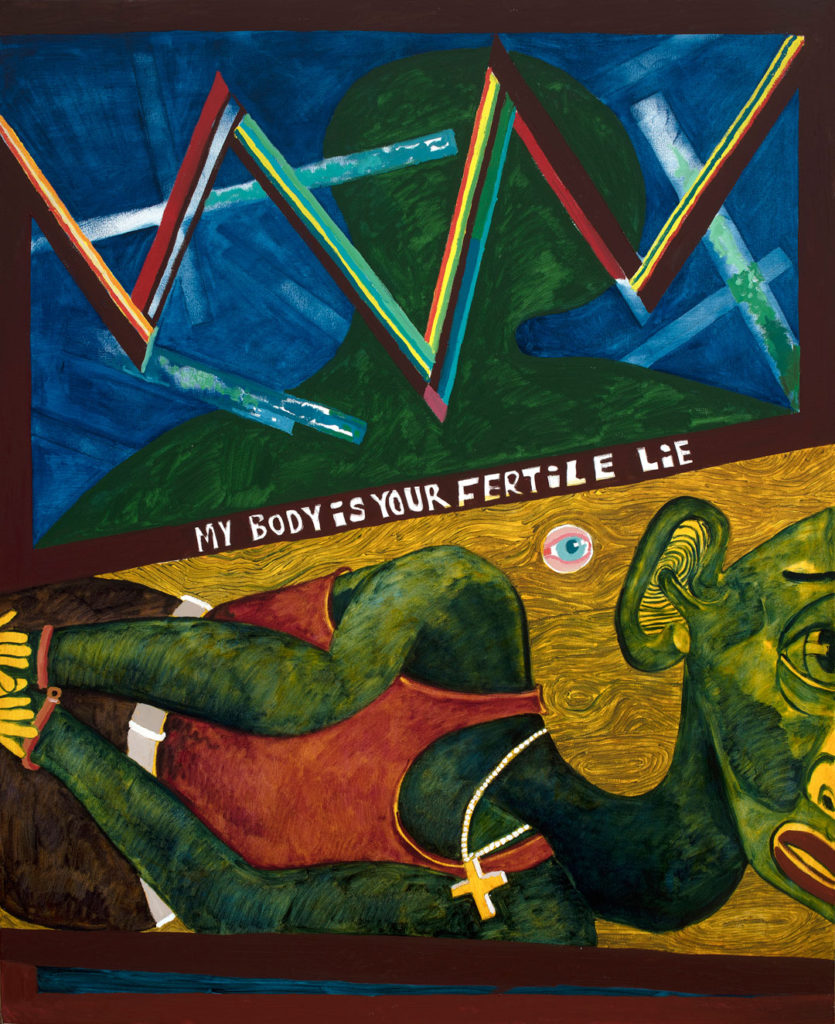

Williams employs the high symbolism of Pop Art, but with very specific touchstones. Gone is the nebulous 1960s commentary on the advertising man, and in its place, Williams presents a compelling, granular look at police brutality through the life and death of George Floyd. In his UNTITLED, ART interview, Williams recalled his shock over George Floyd’s murder: “I couldn’t quite bring myself to believe that something like this was so prevalent… That people just stood there and watched him die. Even I just stood there and watched him die. The police officer had his hand in his pocket and gazed about as if it were an everyday occurrence. And of course, it is.”

Williams created The Death of George Floyd, the center panel of the triptych, in response to this shock. The piece brings to the surface questions around witness and social passivity. Through striking, often discordant use of form, color, and symbolism, Williams both activates and reappropriates looking, turning the accountability onto the viewer.

The Arrest of George Floyd, the left panel of the triptych, features Floyd covered in a pattern of pale fingertips. To the left of Floyd is a jailed Black man framed by the words, “Millions of Blacks in Jail, Prison.” To his left, a white man behind bars is surrounded by a scroll of text: “Millions of Guilty Whites,” pointing to the direct correlation between mass incarceration and the exploitation of Black people on behalf of white America. In the background is a De Stijl-like grid. Here, Williams reappropriates Piet Mondrian’s spiritual vision for geometric form and reverence for the grid to point to social subjugation: “We are all preprocessed by that grid,” Williams stated. Behind Floyd, a church, and to the far left, a single steely blue eye, calling to mind literary icon Toni Morrison and revealing Williams’s enduring interest in cultural exchange—how culture is absorbed and regurgitated. A mix of religious iconography and social realism, the piece speaks to Floyd’s Christ-like immortalization through death and the enduring legacy of police violence and systematic oppression.

In many ways, Williams is wrestling with the same question that writer Zadie Smith posed in a New York Review of Books piece about the work of Kara Walker (NA 2007)—“What do we want history to do to us?”3 Like Smith, Williams is well aware of the elusiveness of this question, and how it changes over time. As Williams told John Yau, the context of a work of art “is constantly being re-evaluated, re-situated in the time in which it’s being talking about,” thus showing his sensitivity to the ever-changing perceptions of the past and present. Many of Williams’s works hold specific meanings while also building signification across time and space. In his interview with the Delaware Art Museum, Williams clarified his goal to “speak up, document, [and] leave a record” in response to the 2014 series of videos documenting the killings of Black men and women such as Eric Garner. Drawing on current events, Williams’s works simultaneously subvert and extend meaning in an era in which meaning and intention, specifically racial discrimination and its subsequent violence, have become intensely clarified due to modern technology. In doing so, Williams both exposes the sanitation of history while critiquing the absurdity of calling it the past. It is no coincidence that Williams’s Black Exodus series brings to mind The Migration Series, 1940-41, a collection of paintings and text by Jacob Lawrence (ANA 1971; NA 1979) that depicts the post-WWI migrations of African Americans from the rural South to industrial North, signaling prescient repetitions within history.

Though extremely appealing to the contemporary viewer, Williams’s works are also like a walk through art history. As a young artist, Williams was told to reappropriate the assumed arts canon. “To take that authority,” Williams told Yau, “break the glass and take the points home.” In Black Universe, Williams uses the tactic of reappropriation to both evoke and elide meaning. As the Birds Fly, Another Planet, 2019, is a visual feast of exchange between animal and alien lifeforms reminiscent of narrative medieval paintings such as Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights, 1500/1505. Each node of relation is rife with potential allegory, referencing anything from basketball to the animal kingdom to eroticism. This beehive approach to world building implies a constant regeneration of life’s intertwining plots. Williams employs storytelling as sense-making, but also points to the impossibility of ever really locating the beginning and end of one story. The longer one looks at a piece, the more the stories grow.

In both his figurative and abstract works, Williams’s symbols constantly subvert the rigidity of semiotics to re-analyze and re-address historical reality. However, it is the willful ignorance of this reality, or truth, that Williams is interested in, rather than pinpointing its exact location. Instead of finding out what truth is, Williams is determined to prod why society constantly struggles against its interrogation. “Where is there a kind of truth if everything repeats itself over and over again without any conclusion?” Williams asked in conversation with Yau. In Black Universe, a semblance of “truth” reveals itself somewhere between the historical and personal.

Black Universe is presented at the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit and Trinosophes in Detroit July 2, 2020 – January 10, 2021. A concurrent exhibition was presented at Luis De Jesus Los Angeles July 2 – October 10.

Rosa Boshier is a writer whose short fiction, essays, art criticism, and creative nonfiction have appeared in or are forthcoming in Joyland Magazine, The Offing, The Acentos Review, Guernica, The Rumpus, Hyperallergic, Literary Hub, Vice, Los Angeles Review of Books, The Guardian, and The Washington Post, among others. She has taught writing, Latinx cultural studies, and art history at the California Institute of the Arts, Otis College of Art and Design, and Pacific Northwest College of Art.