An important friendship and collaboration with the writer Albert Murray underlie the two-part Profile series, 1978-81, by Romare Bearden (ANA 1978). The two men first met in Paris in 1950, where both were studying under the GI Bill. A decade later, in New York, they reacquainted and developed an intellectual and artistic exchange based on mutual interests in art, literature, jazz, and African American history. In 1964, not long after he adopted collage as his primary medium, Bearden enlisted Murray’s assistance with titling his works, a practice he continued with the Profile series. When the artist initially exhibited the collages at Cordier & Ekstrom Gallery in New York—Part I in 1978 and Part II in 1981—Murray also penned the narrative texts presented directly on the wall next to each work. Although based on Bearden’s memories, the texts feature one of the writer’s favorite rhetorical devices, the “second-person singular,” which as scholar Paul Devlin explains, establishes distance and renders memories conditional.1 The men’s partnership was acknowledged at the time; however, as the Profile series was subsequently broken up and dispersed into collections, its details faded away. The High Museum’s “Something Over Something Else”: Romare Bearden’s Profile Series sets out to reanimate the collaborative aspects of this project.

Profile/Part I, The Twenties features Bearden’s childhood memories of living with relatives in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. One of his earliest recollections is attending school: School Bell Time, 1978, is organized with crisp, flat shapes and minimal overlapping, a silhouette of the stern teacher dominating the lower right corner (“Once it was mid-September again, it was back to Miss Pickney and books, blackboards, rulers, and fingernail inspection.”).

Country Band, 1978, demonstrates a more painterly approach to the collage medium, Bearden forgoing clarity for a scene that evokes the conditional quality of memory-work (“You could see them every Saturday afternoon on the street corner, and sometimes they also played at picnics and baseball games.”).

Recurring motifs in Part I include trains, quilts, and conjure women (spiritual healers), which along with scenes of farming, meal preparation, and church revivals paint a vivid picture of African American life in the South. Female sexuality is another frequent theme in Part I, where it functions as the erotic subject of male adolescent fantasies and a testament to the stark circumstances of many poor Black women. Of the scene depicted in the dilapidated room in Railroad Shack Sporting House, 1978, for instance, Bearden recalled to Murray: “When I was old enough, I found out what Liza’s mother did for a living.” These moments figure the artist less as the protagonist of his own story than the ethnographer of others’ lives. Composed through the mind’s eye of a child, the collages poignantly convey moments of adversity and hope, reckoning and joy.

Part I also includes misfortunes more proximate to the artist. Farewell Eugene, 1978, for example, depicts the funeral in Pittsburgh of Eugene Bailey, the young friend who first taught Bearden how to draw. The faces and bodies of the mourners overlap indistinguishably, with shifts in scale that underscore a feeling of emotional disorientation. At the same time, Bearden’s dynamic color sensibility is apparent. It is no coincidence that in all his works, the scraps of papers form an improvisational rhythm akin to jazz, as well as African American quilt-making. Although not always evident at first glance, closer scrutiny also reveals Bearden’s attention to compositional structure. As he shared with Calvin Tomkins for a 1977 New Yorker profile, the artist learned by studying Dutch painting: “I found that, especially with Vermeer and [Jan] Steen, a lot of the work was controlled, like Mondrian’s, by the use of rectangles over rectangles. I really think the art of painting is the art of putting something over something else.”2

Profile/Part II, The Thirties picks up again with memories of Pittsburgh, then shifts to Harlem, where Bearden’s parents lived and where he resettled as a young adult. Scenes of boarding houses, billowing smokestacks, and African American steel mill workers give way to depictions of bustling city streets and jazz clubs. The artist also continued to depict the people intimate to him. Harlem Brownstone Interior, 1980, a bold composition dominated by yellows and blues, depicts three generations of women at a table in an elegant domestic interior. Here and elsewhere, Bearden also indicates his abiding interest in West African art, specifically textiles and masks, which infuse the quotidian scene with ritual significance.

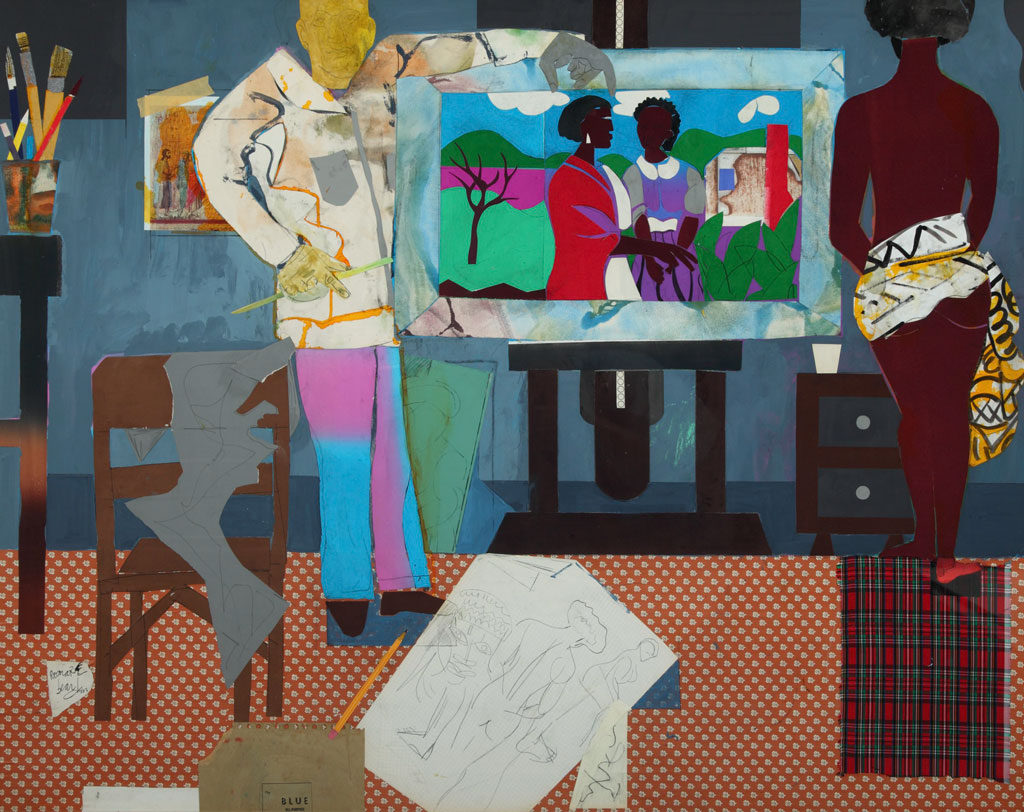

As High curator Stephanie Mayer Heydt indicates, Part II also chronicles Bearden’s coming of age as a visual artist.3 This theme is pointedly registered in Artist with Painting & Model, 1981, the largest collage in the Profile series, and the only to identify explicitly as a self-portrait. As with School Bell Time, Bearden composed it primarily out of flat chromatic shapes and silhouettes. Several art historical references collide in the work, including a reproduction from Duccio di Buoninsegna’s Maestà altarpiece, a drawing of the bronze head of a Benin Oba (king), and on the easel, a reprisal of Bearden’s 1941 painting, The Visitation. In an additional self-referential gesture to his collage work, draped across the chair is the scrap of gray paper from which Bearden cut out his left hand.

Despite its personal subject matter, the Profile series bears little resemblance to a conventional autobiographical narrative. Instead, each collage constitutes an isolated and highly formalized memory, one “fixed on in advance,” as Murray would later write.4 Nonetheless, the serial installation of the works illuminates Bearden’s recurrent motifs and themes, as well as his deft stylistic and technical range with collage. At the High Museum, the inclusion of 24 of the 28 original collages in Part I encourages an immersive viewing experience. Unfortunately, the exhibition includes only 10 of the 19 works in Part II. However, by re-assembling over two-thirds of the Profile series, and re-presenting it as a team undertaking, the show successfully highlights the people and broader contexts that helped shape Bearden’s mature oeuvre. It likewise underscores both Bearden’s and Murray’s artistic legacies, which as Devlin writes, continue “to hurdle into the future, transmitting the past to new generations, if at times in the second person and/or perhaps, as such, in profile.” 5

“Something Over Something Else”: Romare Bearden’s Profile Series is presented at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta September 14, 2019 – February 2, 2020, and the Cincinnati Art Museum February 28 – May 24, 2020.

Susan Richmond is an associate professor of art history at the Welch School of Art & Design, Georgia State University. She is the author of Lynda Benglis: Beyond Process (2013).

- Paul Devlin, “Two American Modernists, Second-Person Singular: Albert Murray’s Words in Romare Bearden’s Profiles,” in “Something Over Something Else”: Romare Bearden’s Profile Series (Atlanta, 2019), 68.

- Bearden quoted in Calvin Tomkins, “Profiles: Putting Something Over Something Else,” New Yorker (November 28, 1977), p. 72.

- Stephanie Mayer Heydt, “Self-Revealing: Autobiography, Narrative, and Bearden’s Profile Series,” in “Something Over Something Else,” p. 31.

- Albert Murray, “The Visual Equivalent of the Blues,” in Romare Bearden: 1970-1980, ed. Jerald L. Melberg and Milton J. Bloch (Charlotte, NC, 1980), p. 17.

- Devlin, p. 71.