An accomplished artist and teacher, Robert Blackburn (ANA 1981; NA 1994) dedicated his life to collaboration and diversity in the arts. This is best exemplified by the Printmaking Workshop, now the Robert Blackburn Printmaking Workshop, which he established in 1947 in his New York City studio. It was a dynamic environment of open exchange and shared resources, and it continues today as one of the most impactful and long-lasting creative communities to emerge in New York this past century. With printmaking at its core, the workshop from its start was an inclusive space where an international and multiracial mix of artists, printers, and creatives could learn from each other and expand their practices. For more than six decades, it has served an extended network of individuals, especially artists of color from the United States and abroad, and provided an instrumental platform for underrepresented voices.

The illuminating exhibition Robert Blackburn & Modern American Printmaking, curated by Deborah Cullen and organized by the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service, celebrates this impressive history along with that of Blackburn’s personal artistic evolution over 70 years as both a collaborator and printmaker. The exhibition opens this Saturday, March 20, at the Detroit Institute of Arts and will be on view through September 5, with future presentations at the Figge Art Museum, the Hyde Collection, and the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center at Colorado College. I visited the show during its first presentation at the Nelson-Atkins Museum.

The exhibition is a timely consideration of Blackburn’s influential reach and recognition of his accomplishments by a major American institution.1 Cullen, who first encountered Blackburn when she was an intern at his workshop during the 1980s, eventually became a devoted participant and advocate, helping Blackburn run the organization for many years. She has published extensively on Blackburn’s work and activities, and this exhibition reflects her research and sensitively captures the nature of the relationships that energized Blackburn’s circle.

The son of Jamaican-born parents, Blackburn moved to Harlem with his family when he was seven years old. The thriving cultural life of the Harlem Renaissance which revived African American art and literature was fully underway, and the young Blackburn immersed himself in the educational opportunities that it had to offer. By the 1930s, he sat in on sessions at Charles Alston’s 306 salon and Augusta Savage’s Uptown Arts Laboratory, as well as attended classes at the Harlem Art Workshop and the Harlem Community Art Center. People he met in these settings formed the beginnings of his network. A Works Progress Administration (WPA) facility, the Harlem Community Art Center offered free printmaking classes where students largely taught themselves and each other. Blackburn first learned to print in this context and, as a result, gained direct understanding of lithography’s technical processes. Unusual for printmaking instruction at the time, this hands-on approach sparked Blackburn’s lifelong admiration of the medium’s material intricacies and a commitment to experimentation in the printshop.

In 1940, Blackburn began courses at the Art Students League. Up to that point, his work aligned in subject matter and style with the art he had discovered in Harlem’s salons and workshops, including that of the great African American Modernists, Mexican muralists, and social realists. The lithograph Refugees (aka People in a Boat), 1938, is a moving example of Blackburn’s figurative compositions during this period. It is a monumental scene of displacement and unknowing heightened by Blackburn’s abilities to achieve dramatic light and volume in lithography. Although many of his colleagues stressed the responsibility of Black artists to depict the experiences of their people,2 Blackburn desired to explore abstraction more fully, especially ideas put forth by the European avant-garde which he enjoyed discussing with friends Will Barnet (ANA 1974; NA 1982) and Ronald Joseph. As a Black man, he had been hesitant to explore beyond Harlem and never felt fully at home in the Downtown circles,3 so his time at the Art Students League expanded his exposure to the people and ideas shaping the larger New York scene. In time, his attention turned to a deeper investigation of what Cubism, and related styles, had to offer.

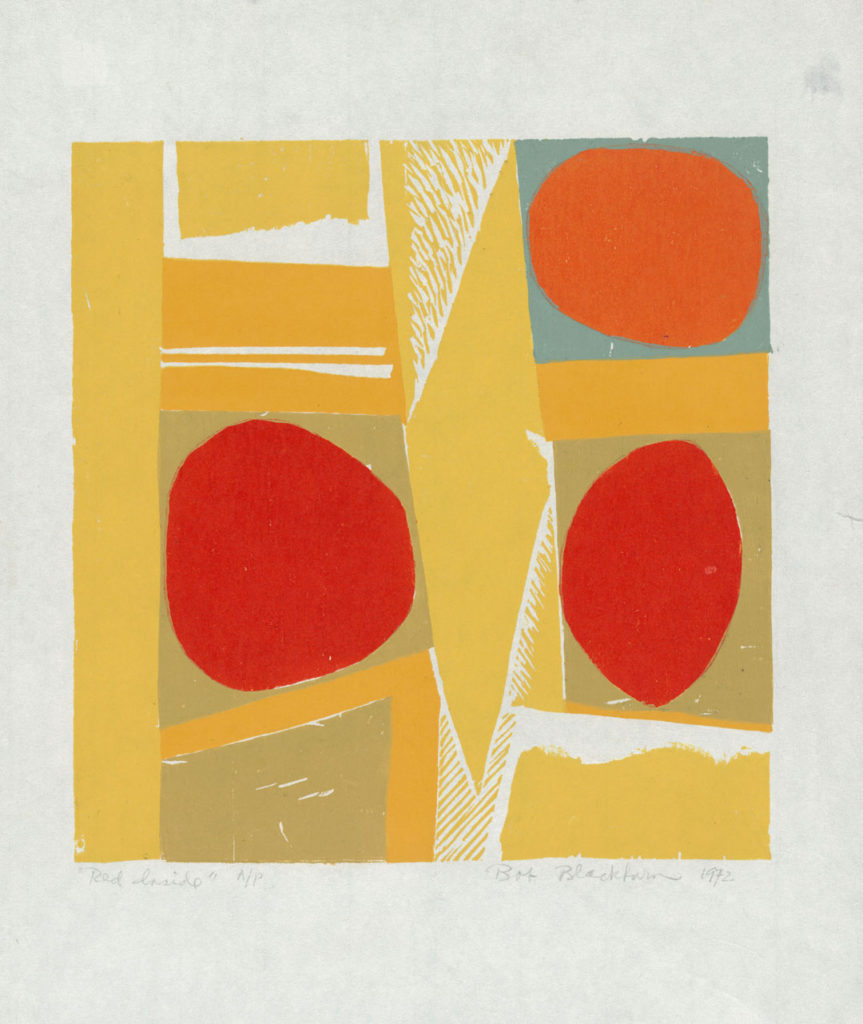

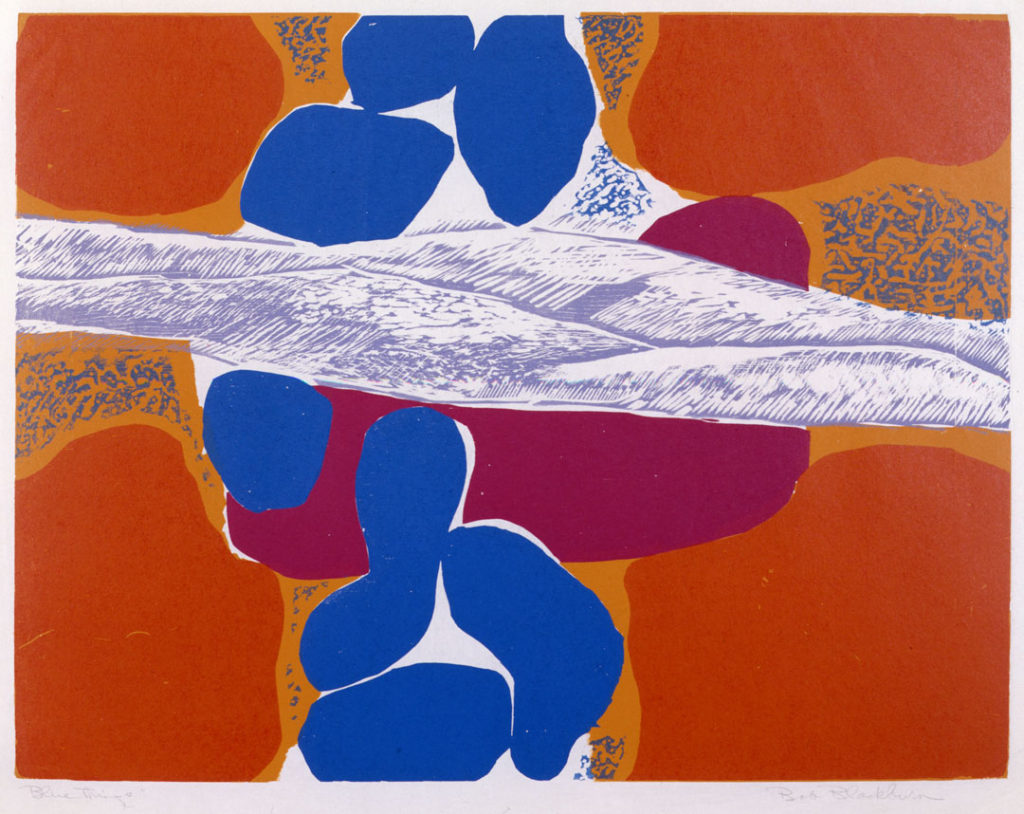

Although painting dominated midcentury discourse surrounding abstraction, Blackburn favored printmaking to achieve his pictorial arrangements of color and shape. Blackburn, who considered lithography an art form as opposed to a reproductive format, once stated, “the medium is not the thing in and of itself… it’s what the artist does with it that matters.”4 In the decades that followed, Blackburn’s prints became increasingly abstract. Works such as Faux Pas (aka Unfinished Note) and Red Inside from the 1960s and 1970s demonstrate these explorations which continued into the 2000s with his last major project realized posthumously in 2005—a series of mosaic murals for Manhattan’s 116th Street subway station that translated his graphic works into permanent public art.

Finishing his coursework at the Art Students League, Blackburn established the Printmaking Workshop in 1947 at his private studio on West 17th Street where he invited fellow artists to print on the press he had installed there. As Blackburn shared his expertise with others, his skills were also noticed by Tatyana Grossman, the founder of Universal Limited Art Editions (ULAE) who sought to turn a new generation of artists on to prints.5 She hired Blackburn as master printer in 1957, and he worked there for seven years with several works produced during his time at ULAE included in the exhibition. Upcoming talents, such as Lee Bontecou (NA 2004), Grace Hartigan, Robert Rauschenberg (ANA 1982; NA 1985), and Larry Rivers (ANA 1982; NA 1994), came to ULAE, and some were hesitant to explore the medium they considered extremely outdated. Supported by Blackburn’s technical knowledge and enthusiasm for experimentation, they proceeded, despite their reluctance, to produce ground-breaking—as well as critically and commercially successful—projects that launched the great printmaking renaissance of 20th-century American art.

While he built connections in the mainstream art world, Blackburn remained driven to increase access for voices typically excluded from those spaces. Despite limited resources, he and his colleagues continued to develop the workshop and maintain an environment where all were welcome. They invited artists from diverse cultural backgrounds, including African American and Native American practitioners, and cultivated an international network that looked to East Asia, India, Africa, and Latin America. They also initiated printmaking programs for underserved youth around New York, and as a result, made printmaking and the creative process accessible to many.

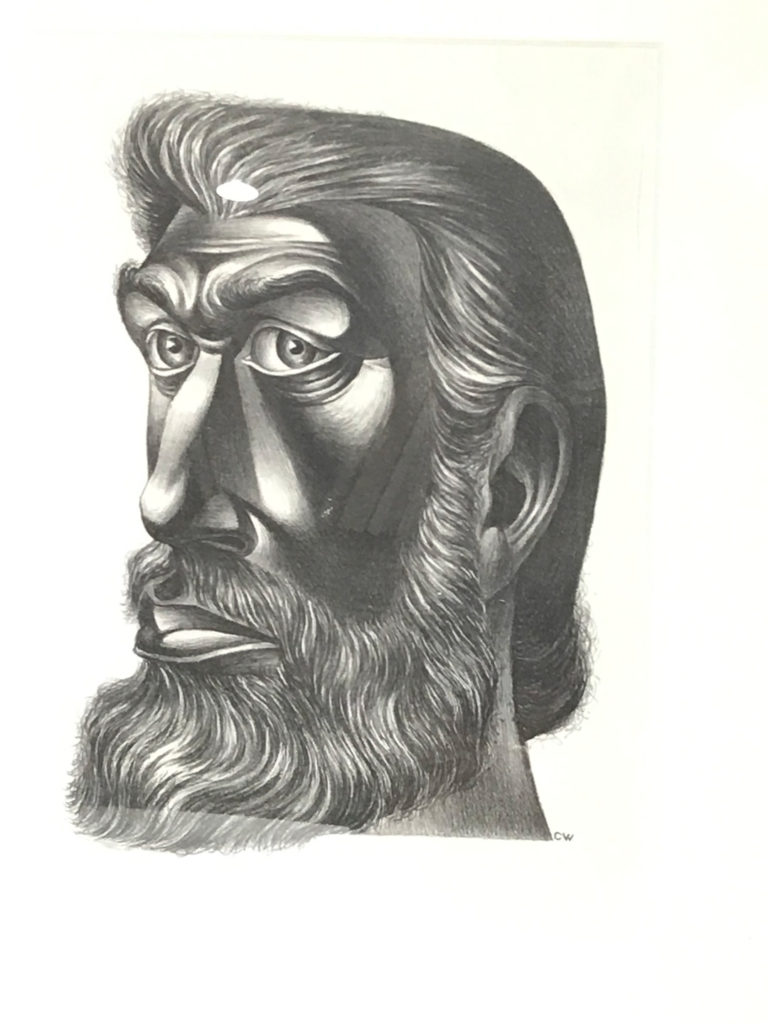

Over the years, artists who printed with Blackburn or pursued their own explorations at the facility include Emma Amos (NA 2006), Will Barnet, Elizabeth Catlett (NA 2002), Ed Clark, Melvin Edwards (ANA 1992; NA 1994), Antonio Frasconi (ANA 1962; NA 1969), Krishna Reddy, Faith Ringgold (NA 2006), Juan Sanchez, and Charles White (ANA 1971; NA 1974), among dozens of others.6 The current exhibition intersperses works by many of these artists with Blackburn’s own pieces, providing a full sense of the creative dialogue the workshop fostered. Evolving from its informal beginnings, the workshop became a public nonprofit in 1971 and today is part of the Elizabeth Foundation for the Arts. The organization continues to promote Blackburn’s mission through an active program of classes, exhibitions, and publications involving emerging and established artists who bring new perspectives from the communities they represent.

Robert Blackburn & Modern American Printmaking reminds us that collaboration is a vital aspect of the creative process and an approach that has been passed down through generations. Blackburn is among those who have shared the mindset with others, having first embraced it as a young man exposed to Harlem’s supportive intellectuals and the group work ethic promoted through the WPA. During the 1960s and 1970s, Blackburn’s workshop participated in the push toward collective action and organized advocacy in the arts. Today, his legacy influences the growing group of artists inspired to support their peers by establishing residencies and workshops of their own. Stony Island Arts Bank founded by Theaster Gates (NA 2017) on Chicago’s South Side, Kehinde Wiley’s Black Rock in Dakar, Senegal, and Ryan Trecartin and Lizzie Fitch’s rural project near Athens, Ohio, are some examples where artists are carving out production spaces for each other. Touching upon this impulse that he helped to foster, Blackburn once observed, “No one person owns art; it is something you pass on.”7

Robert Blackburn & Modern American Printmaking is presented at the Detroit Institute of Arts from March 20 – September 5 and is scheduled to travel to the Figge Art Museum (October 9, 2021 – January 9, 2022), the Hyde Collection (January 29 – April 24, 2022), and the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center at Colorado College (May 14 – August 7, 2022). It was first presented at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (September 12, 2020 – February 28, 2021).

Gretchen L. Wagner is a curator and art historian based in St. Louis. She has completed projects featuring modern and contemporary art at institutions internationally, including the International Print Center New York, the Museum of Modern Art, Pulitzer Arts Foundation, Saint Louis Art Museum, Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College, WIELS Centre d’Art Contemporain, and Williams College Museum of Art, among others. Wagner holds degrees in Art History from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and Williams College.

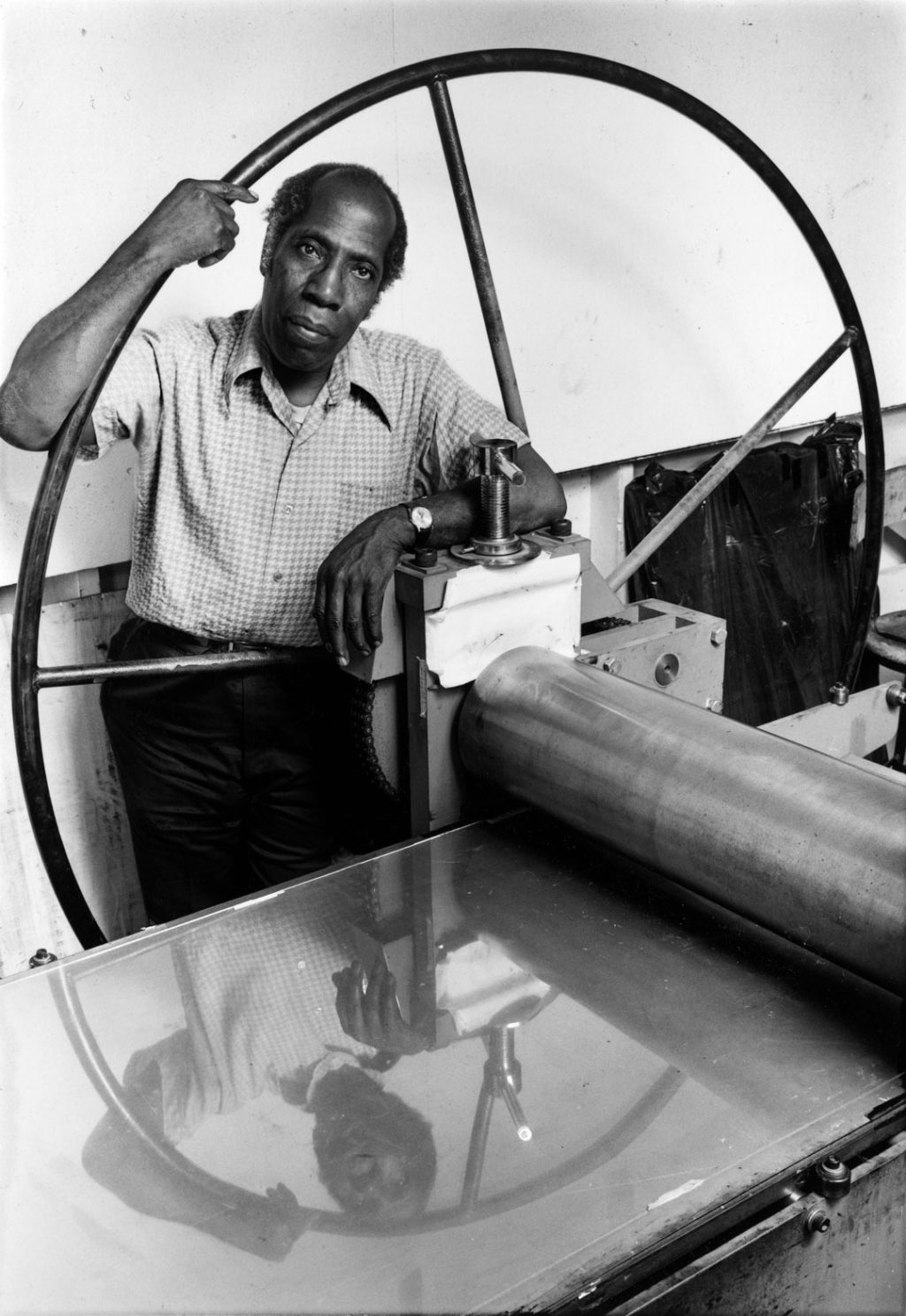

Header image: Robert Blackburn, 1987. Photograph by Peter Sumner Walton Bellamy

- The current exhibition follows previous exhibitions dedicated to Blackburn’s life and work including Robert Blackburn Passages at the David C. Driskell Center in 2014, Creative Space: Fifty Years of Robert Blackburn’s Printmaking Workshop at the Library of Congress in 2003, Bob Blackburn’s Printmaking Workshop: Artists of Color at the Hillwood Art Museum and the Bronx River Art Center and Gallery in 1992, and Through A Master Printer: Robert Blackburn and the Printmaking Workshop presented at the Columbia Museum of Art, the Arkansas Art Center, and the Mississippi Museum of Art in 1985-86.

- For more information regarding this discourse, see recent projects that have addressed abstraction by African American artists, including: Mark Godfrey and Zoe Whitley, et al., Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power (London: Tate Publishing, 2017); Courtney J. Martin, ed., Four Generations: The Joyner/Giuffrida Collection of Abstract Art (New York: Gregory R. Miller & Co., 2016); and Kellie Jones, Energy/Experimentation: Black Artists and Abstraction 1964-1980 (New York: The Studio Museum in Harlem, 2006).

- Deborah Cullen, Robert Blackburn Passages (College Park, MD: David C. Driskell Center for the Study of the Visual Arts and Culture of African Americans and the African Diaspora at the University of Maryland, College Park, 2014), 41-2. The exhibition catalog presents an extensive examination of Blackburn’s life and work and is the source for much of the biographical information provided in this article.

- Noah Jemison, Bob Blackburn’s Printmaking Workshop: Artists of Color (New York: Printmaking Workshop, 1991), 17.

- For a history of ULAE and its place in the American printmaking boom, see Jack Cowart, Proof Positive: Forty Years of Contemporary American Printmaking at ULAE, 1957-1997 (Washington, D.C.: Corcoran Gallery of Art, 1997), and Elizabeth Wyckoff and Gretchen L. Wagner, Graphic Revolution: American Prints 1960 to Now (Saint Louis: Saint Louis Art Museum, 2018).

- A collection of over 2,000 prints produced at the workshop by participating artists was acquired by the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division in 2006.

- Cullen, Robert Blackburn Passages, 15.