When the 85-year-old artist Peter Saul (NA 2012) began showing his shockingly aggressive and sadistically political paintings in the 1960s, his audience wasn’t quite primed for the affront. But in 2020, a time when political controversy has become almost banal in its normalcy, Saul’s paintings aren’t just palpable, they’re pretty damn on point.

Taking up two floors at the New Museum in New York is Saul’s very first survey in the city, and it’s not going unnoticed. Established critics like Peter Schjeldahl of The New Yorker and Holland Cotter of the New York Times, along with trendsetting outlets for youth culture like Hypebeast and Vice’s Garage agree: Peter Saul: Crime and Punishment is definitely worth a gander—or, as Schjeldahl puts it, is “the timeliest as well as the rudest painting show of this winter.”

Saul’s paintings resonate with today’s climate in terms of subject (more on that in a minute), and style. His later works in particular, those from 1967 to 2018, which are hung salon-style on the museum’s fifth floor, predate the cartoonish, neo-surrealist figuration that’s become so popular amongst younger painters as of late. Artists like Nicole Eisenman, Jamian Juliano Villani, Jordan Kasey, or Nicolas Party could have easily picked up a thing or two from Saul, whose greatest influences may not have been artists at all—but magazines and comics, like MAD, for instance. (It’s no surprise that a number of the paintings in the exhibition come from the collection of KAWS, an artist whose accessible, cartoonish characters have made him one of the most sought-after contemporary artists/designers of today.) Saul’s style, with fluorescent Day-Glo hues, exaggerated caricature-like figures, and large-scale canvases, is enough to make you feel you’re being affronted by a burst of energy strong enough to make your cheeks flush or your stomach turn—depending on your political leanings.

Politics, are, of course, unavoidably addressed in Crime and Punishment, yet Saul’s ideological position may be more ambiguous than the sum of his rendered antagonists suggests. Saul and his paintbrush have waged their own wars, wherein no public figure is safe from Saul’s humiliating, hate-driven characterizations. Perhaps most known are his Vietnam War paintings, a series which began in 1965 in response to (and in protest of) the war, and ended in 1970 with the painting Pinkville. In the picture, a man in a U.S. soldier’s uniform uses his four arms to violate and execute four naked Vietnamese women. Each arm is inscribed with words describing his transgressions, such as “ARSON AND TORTURE” and “SADISTIC RAPE.” Below him is a pathway made of dynamite, which awaits detonation by the soldier, who holds a lit match. The painting speaks to the horrific violence of the war, most notably the events of March 16, 1968, when 100 U.S. soldiers entered Son My (referred to by Americans as My Lai) searching for a group of Viet Cong soldiers. Unable to find them, the soldiers, without any provocation, proceeded to brutally massacre more than 500 people, and rape and torture many more. Saul’s interpretation of the event condemns the violent brutality while manifesting the soldiers’ sadistic desires—a nuanced take rendered matter-of-factly.

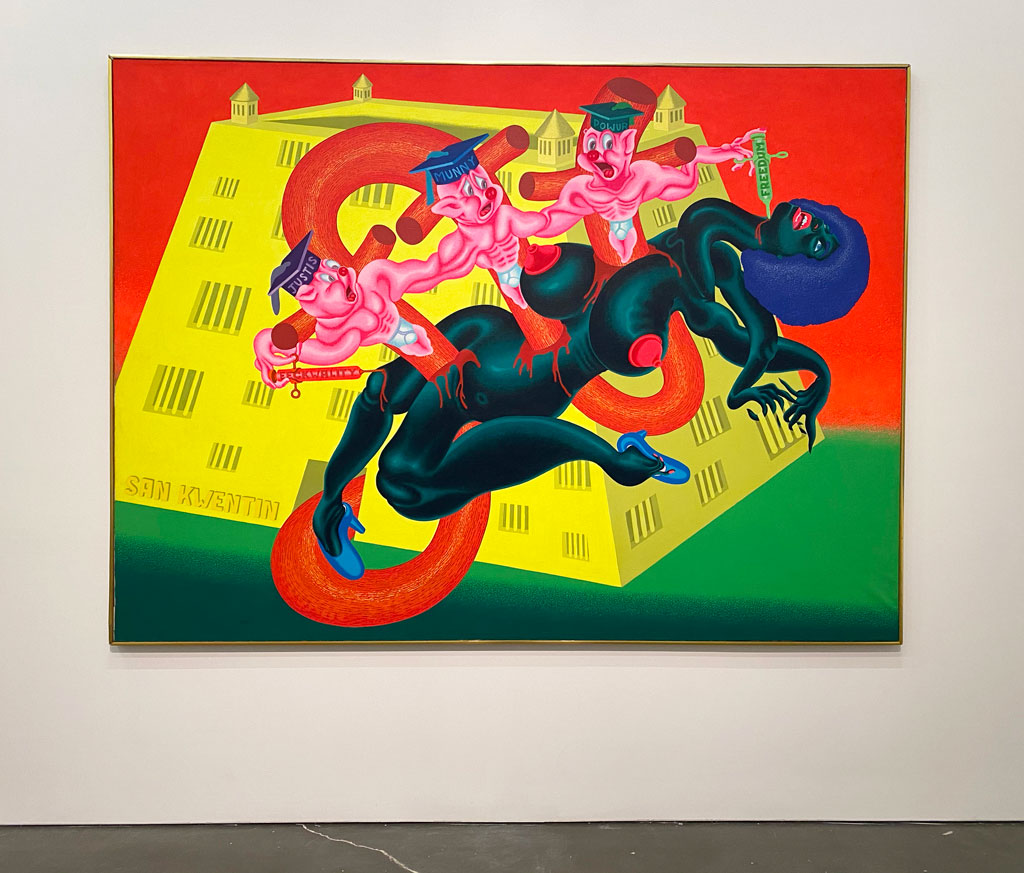

Female subjects in Saul’s paintings are almost always depicted with exaggerated racial stereotypes and overly sexualized bodies. Presented as victims, in contrast to the villains Saul critically annihilates, these women subjects demand empathy, pity, and solidarity, while also satisfying the perversion Saul treats as inherent to the American political agenda. Following the Vietnam War, Saul became particularly critical of police brutality and systematic racism, especially in his then-home state of California. Self Defense, 1969, for instance, depicts the academic and activist Angela Davis, who was persecuted by the U.S. government for her involvement with the Black Panthers. (UCLA attempted to fire Davis from her teaching position because she was a member of the Communist Party. A year later, she was tried and imprisoned for her alleged complicity in a courtroom hostage crisis, leading to protests across the nation that called for her release.) In Saul’s painting, Davis is torn apart while white police officers leer at her naked body. And in San Quentin #1 (Angela Davis at San Quentin), 1971, the activist’s body is impaled in front of the prison while three cartoon pigs, representing “JUSTIS,” “MUNNY,” and “POWUR” look on with amusement. In consuming these works, we become shocked and outraged by the brutality of the nation’s ruling government, while recognizing our own complicity in indulging in the salacious spectacle.

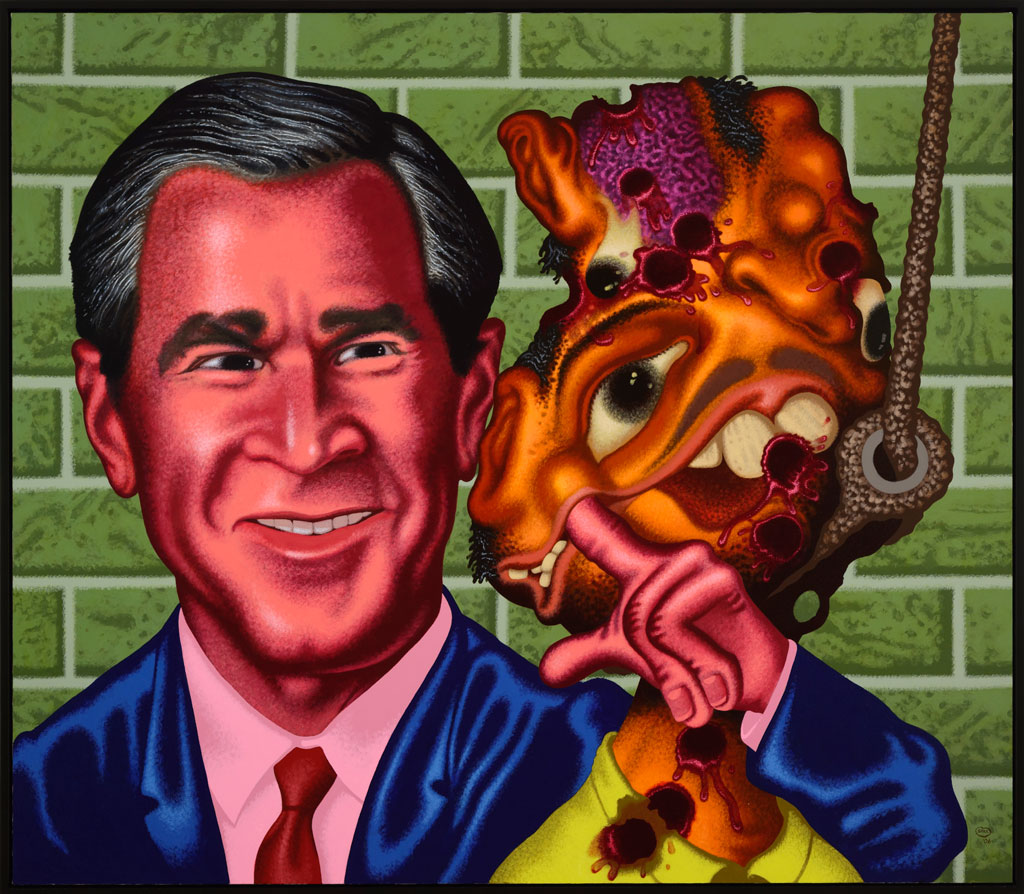

Saul was certainly not alone in painting public figures and cartoon imagery in the 60s and 70s; Pop artists like Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein became famous for their use of this iconography. Unlike Saul, however, they maintained a cool distance between the form and content of their works, instead using recognizable imagery to comment on the nature of images and advertising itself—rather than on the subjects those images or advertisements represented. For Saul, presidential portraits present opportunities for humiliation and criticism. In 2006, for example, Saul painted Bush at Abu Ghraib in response to the torture of Iraqi prisoners by U.S. troops at Abu Ghraib prison. Fast forward to 2020, and there is no shortage of contemporary artists liberally applying the likeness of the current president to Saul’s familiar tactics (as seen in Saul’s Newt Gingrich vs Orphan Annie, 1995; Ronald Reagan in Grenada, 1984; or Bush and Hitler in Gulf War II, 2003), which is perhaps why Saul decided to go a different, neutral (yet more controversial) route with his recent presidential portraits.

In Donald Trump in Florida, 2017, the former reality television star interacts with a crocodile in myriad capacities—some honorable, some violent; some gentle, some comical. Saul explains the impetus for another 2017 painting, President Trump Becomes a Wonder Woman, Unifies the Country and Fights Rocket Man: “It occurred to me that the only fresh painting of Donald Trump that could be painted would be positive. He’s been trashed by every single artist in the world.” While we may no longer be looking to Saul for impassioned critical dissidence in the current moment, we can appreciate his oeuvre as a record of American political dissatisfaction of the past—one that stylistically resonates with young generations of today who are tasked with forging their own strategies of resistance in art-making.

Peter Saul: Crime and Punishment is presented at the New Museum in New York City February 11 – May 31, 2020.

Loney Abrams is an artist and writer based in Brooklyn, New York. She co-runs Wretched Flowers with Johnny Stanish, which may be found online here, and on Instagram here.