In 1937, pioneering choreographer Martha Graham noted the power of dance to express “the depths of man’s inner nature, the unconscious, where memory dwells.” Graham’s work embraced abstraction alongside the Abstract Expressionists of the 1940s. Those parallel philosophies are front and center in The Space Between Us, the exhibition of paintings and ceramic vessels by Lorraine Shemesh (NA 2004).

The Space Between Us—which shows at Peters Projects in Santa Fe until August 17, and is exhibited again from September 12 through October 16 at Gerald Peters Gallery in New York—furthers Shemesh’s philosophical exploration of the relationship between movement and psychology.

Since the early 1990s, Shemesh’s investigations of the human form have toed the line between formality and abstraction. The paintings in The Space Between Us grew out of her 2009 Intersections series, which featured large-scale canvases of two interlocking dancers. Both the canvases and the 10 ceramic vessels exhibited alongside them display a preoccupation with shadow and sunlight, along with intricate, swirling patterning, and the essential circular figuration created by two interlocked dancers.

“Ballet denies the existence of gravity, so all the movement is vertical, toward heaven,” Shemesh explains in an accompanying video at Peters Projects. She cites her dance background as inspiration for the paintings; the featured vessels were inspired by sedimentary rock formations Shemesh observed on a trip to Abiquiú, New Mexico, where Georgia O’Keeffe lived and painted. In an email interview, she elaborates: “The warmer color palette in the new work, in both the paintings and work in clay, was inspired by the landscape surrounding Santa Fe, and the proportion of sky to land made me want to open and simplify the work that came afterwards. Certainly, the clarity of the light in this part of the country is extremely affecting, as well.”

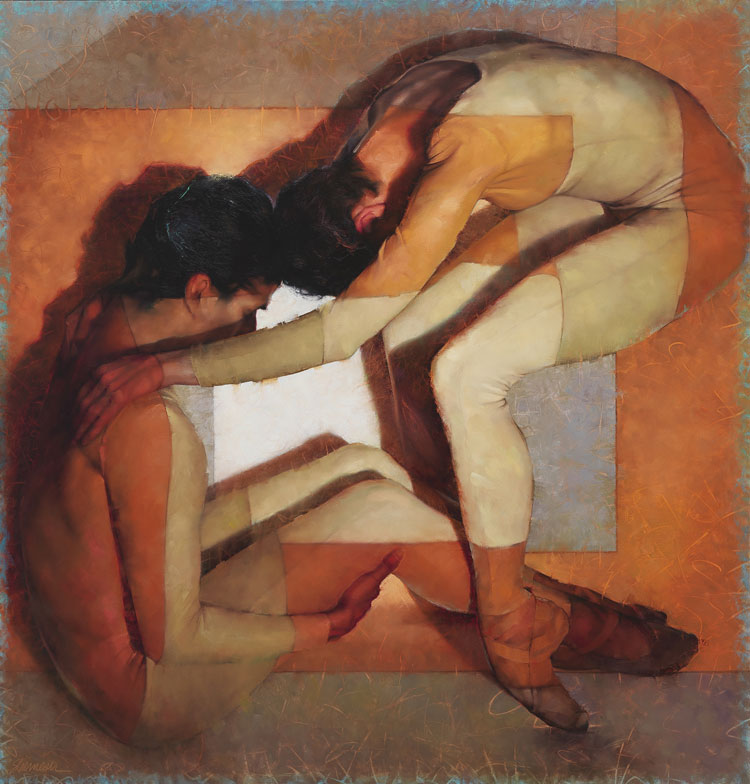

The tans and beiges in Attached, a 2018 oil on canvas, also recall the adobe architecture of New Mexico. The motion Shemesh depicts between the intertwined figures is set off by a burnt orange square surrounding the circle of bodies. The blinding white center of the painting underscores the blank space between the dancers, suggesting the viewer’s ability to project an individual interpretation of this relationship onto the canvas. Shemesh’s signature attention to realist musculature and compelling shadows offsets the abstract geometry surrounding the two figures—the result suggests a dance between inner contemplation, reflected in the bowed heads of the dancers, and physical harmony.

The design relationship between the paintings and the vessels is most clearly seen in Puzzle, a 2014 oil on canvas, and the porcelain Large Black & White Woven Neriage Cylinder, 2017. The pale yellow and black patterns of Puzzle suggest fragmented, jigsaw shadows. These forms are projected upon the dancers and the wall behind them, as the painting follows a swirling spiral gesture initiated by the juxtaposition of the central figures. The contrasting palette also recalls the diamond patterns of a harlequin costume, lending a playful, free-associative quality to Puzzle. As in Attached, the attention to detail in the human forms contrasts with the abstraction of the shadow patterning. At the show’s opening in Santa Fe, local painter Jerry West pointed to the intricate folds of applied paint that adorn the arched neck of one dancer. The other side of the neck is rendered intriguingly amorphous, suggesting blurred motion and emphasizing Shemesh’s consistent toeing of the line between abstraction and realism.

In Large Black & White Woven Neriage Cylinder, Shemesh uses the Japanese clay process called neriage in order to mirror and subvert the same organic patterns of movement and colors present in Puzzle. Of that process, she writes, “The shifting of the initially rigid structure is quite compelling as the piece evolves.” Shemesh also cites the graphic patterning of African Kuba textiles, which employ a similar color palette, as inspiration for her ceramic works. The rhythmic patterns adorning the porcelain vessel are lighter and more whimsical than those of the painting, suggesting sheets of paper floating on a swirling wind.

Other ceramic explorations are more minimalist. White & Toast Hive, a stoneware and porcelain work from 2016, translates the paintings’ preoccupation with circularity into an egg-shaped opening at the top of the vessel. Its elegant motion is highlighted by a white swirl that crests a wave above and around the aperture.

While light, shadow, space, and rhythm provide an ongoing dialogue between the paintings and ceramics, the locked bodies in the canvases also intensely interrogate ideas of intimacy and connection. They spark an exploration of the psychology of one human form in relation to another, and the relative distances and intimacies between the selves housed in each body. As Shemesh explains, “The poetry in painting has to do with not how well you paint the object, or the figure, or the mountain. It has to do with the space between things. The space in between, the air—that’s where the potential for poetry happens.”

The Space Between Us is presented at Peters Projects in Santa Fe (June 21 – August 17, 2019) and Gerald Peters Gallery in New York City (September 12 – October 16, 2019).

Molly Boyle is a writer and editor living in northern New Mexico. She is a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and Brown University, and a former editor at Penguin Random House.