“The water lilies are on the pond in Maine and I’ve been looking at them for 50 years but I never touched them because of Monet… But I said you’re going to do it, and I just did it,” Alex Katz (ANA 1990; NA 1994) remarked in an interview for Phaidon upon beginning his series of paintings of Maine’s water lilies, on view at Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris through September 2. It is not a reinterpretation of Monet’s—unlike many American artists who wanted to learn from Monet’s environment, Katz never went to Giverny—but a genuine tribute to these French masterpieces. According to his autobiography, Invented Symbols, when Katz first came to Paris in 1965, and after Franz Kline said to him, “If you think our paintings are big, wait until you see some of them in Europe,” he visited Musée de l’Orangerie where he saw Les Nymphéas (The Water Lilies) for the first time. With his homage to Monet, Katz reuses codes from impressionist painters, such as large formats and reflections of lights, to deliver a modern American version of those iconic paintings.

Although Katz is one of the most important proponents of figurative art of his generation, this is his first solo show in a Parisian museum, which comes after his first major retrospective in France curated by Éric de Chassey at Musée de Grenoble in 2009, Alex Katz, An American Way of Seeing. Now Katz’s water lilies are exhibited as part of the Musée de l’Orangerie’s Contrepoint contemporain (Contemporary Counterpoint) series centered around the chefs d’oeuvre of the house. Because good news never arrives on its own, Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac just showed Red Dancers, an exhibition of new paintings and works on paper by the artist, all relating to the medium of dance, which he has been working on these last few years.

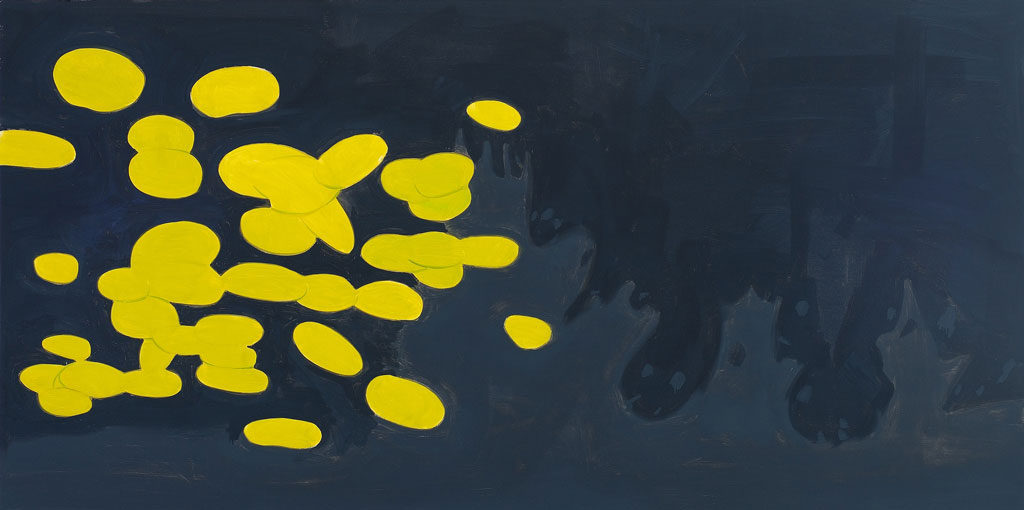

An entire space in the lowest part of the museum is dedicated to Homage to Monet 5, an enormous and immersive painting. Facing it can be quite bewildering: the water lilies are slightly offset from the center of the painting, which challenges our perception of the centrality of the work of art and enables us to feel that the side of the painting came almost by accident. When I was there, several visitors walked around, searching to find the appropriate perspective, but here’s the thing: there is no right or wrong approach in looking at this painting. Katz’s intention behind it is so impactful and straightforward that we are mesmerized wherever we are.

The color palette also questions our conceptions of space and light. By playing with contrasts between yellow forms and a ghostly-shaded, deep blue background, Katz distances himself from the initial subject. Are they the water lilies themselves? Or are they reflections? The choice of the colors here forms a precise and calculated discourse, but also a series of enigmas. Katz describes color as a means of expressing life and of capturing the present moment in order to achieve a particular effect, and that is what this painting is all about. In Homage to Monet 5, Katz not only translates the light of a special moment, but shows his ability to create a new world with complex colors and unexpected forms.

Katz was born in 1927 in Brooklyn to a recently emigrated Russian family. He went to the Woodrow Wilson Vocational High School to study classical drawing techniques and industrial design: he wanted to become a commercial artist. Following these initial years, he enrolled in the Commercial Art department at Cooper Union to better achieve his objectives. The instruction was strongly oriented in the Modernism and Avant-Garde movements. Although Katz said he was fascinated by the Abstract Expressionist painters of his childhood, such as Jackson Pollock, he was never tempted by abstraction.

We find influences of this early environment in the way Katz opposes the backgrounds in his paintings to his portraits and creates kinds of collages. In May, during a conversation hosted by the Louis Vuitton Foundation, which is currently exhibiting some of his works, he explained: “Pollock, Monet were spreading elements on the canvas without any explanation. I wanted to represent things, new things. The grammar of my painting comes from abstraction, but the idea is to give a new vision of it.”

In 1949, Katz received a summer scholarship to attend the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture. There, he was introduced to outdoor painting in Maine landscapes, far away from the modern techniques and urban landscapes he had previously worked with. The direct confrontation with the wilderness freed him from the action of conception: there were no preliminary sketches, but a direct capture of the landscape on the canvas, which brought him to no longer focus on the conception itself, but rather on the image and sensibility of the moment.

Katz quickly began to focus on Maine’s colors, and while he used the impressionists’ techniques to capture the fleeting moment, his palette was much darker and more vibrant. Color has always been a central element in Katz’s art and he affirms himself as a true colorist. A guide at the museum told me that since purchasing a little house in Lincolnville in 1954, Katz spends every summer there, continuing to transcribe Maine’s bright summer lights in his landscapes. Even though he creates landscapes proportionally less than portraits, he has been working on them since that first summer in 1949.

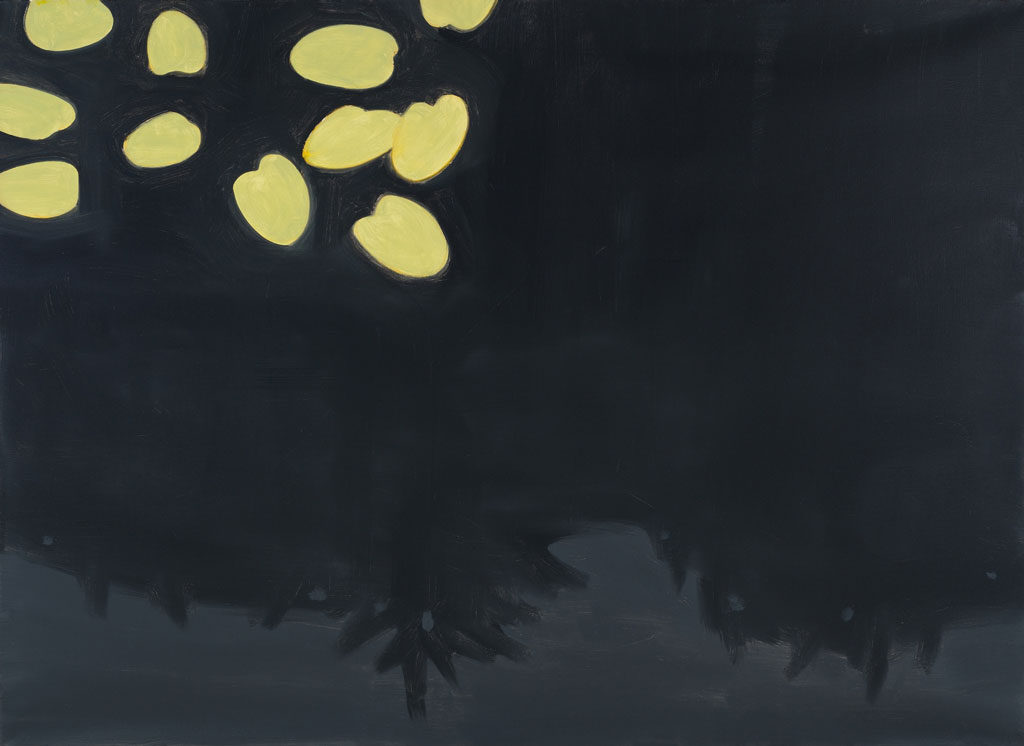

Katz’s interest in seriality is presented in the second part of the exhibition where variations of water lilies are shown in a circular room preceding Monet’s Nymphéas. Pickerelweeds and water lilies take turns in a successive way. Here, the paintings are much smaller than the other ones, revealing other aspects of Katz’s treatment of landscapes. Some of them are actually the first draft of bigger paintings, such as Homage to Monet 2. We can see the rapid brushstrokes that capture the lynchpin moment he observed.

Impressionist paintings are a source of inspiration for Katz in their use of colors to transcribe the depiction of the light in their elaborated landscapes, but there is a major difference in the conception of the paintings. The 19th century painters took a fairly long time in realizing their works of art. On the contrary, Katz wants his paintings to be forceful and instantaneous. In this purpose, he makes a sketch or an oil painting to faithfully capture the essence of a landscape at an exact moment. Then, he willingly forgets about it: Katz distances himself from the landscape he just painted in order to reflect on how it made him feel. The last step is where Katz’s artistic intention is at its best: even though his paintings are massive, he often realizes them in one day. By using this method of estrangement between the first draft and the final version, he delivers a pure and visually powerful interpretation of his subjects. From the first drawing to the last painting in the Homage series, the landscape remains the same, but the narration behind each is profoundly divergent. After a time of decantation, the paintings are more mechanical, and paradoxically reveal the instantaneousness of the moment.

In Invented Symbols, Katz states, “Art from any period can be relevant. I feel closer in time to some earlier artists than to some of the most recent contemporary artists, and the opposite is also true. Nothing is permanent: reality, old art, and new art are all in constant motion.” Almost 100 years divide Monet’s Nymphéas from Katz’s water lilies. The most impressive aspect in this series is Katz’s renewal and modernization of all the interrogations that Monet’s chefs d’oeuvre ask us, bringing to light Katz’s conception of art over time.

Contrepoint contemporain 3: Alex Katz. Nymphéas – Homage to Monet is presented at Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris, France, May 15 – September 2, 2019.

Léa Miranda is a graduate student in law and the history of art at La Sorbonne (Université Paris 1 – Panthéon-Sorbonne). Focusing on the intersections between the two disciplines, her research offers a new approach to the study of cultural heritage and contemporary art trends.

Miranda has professional experience in museum administration (Musée d’art contemporain du Val-de-Marne and Maison Européenne de la Photographie in Paris), as well as a three-month placement in curatorial affairs at the National Academy of Design. She is currently an intern in the Contemporary Art and Photographs department at Christie’s Paris.