Last month, before cities and states around the country issued stay-at-home orders, Zürcher Gallery in New York City presented an exhibition of new and recent paintings, aquatint etchings, drawings, and relief sculptures by Kyle Staver (NA 2015). I was fortunate to view the eponymous exhibition immediately after it opened and before the gallery moved the exhibition online. The day I visited, I noted the transition from an unusually quiet street outside Zürcher Gallery into a world of similar dreamlike eeriness. Within this uncanny and theatrical space, Staver’s work greeted visitors with a beguiling mix of tension and familiarity.

Throughout her practice, Staver, who is based in Brooklyn, has been examining human nature through tableaux, scenes from life, and narratives by means of painting, drawing, printmaking, and sculpture to peculiar effect. Staver’s practice is traditional on the one hand—she incorporates Renaissance motifs, meticulous etching methods, and relief techniques that date back to ancient times—and, on the other hand, avant-garde for that very reason. In the case of this exhibition, her choice of subject matter—a range of biblical, mythical, folkloric, and literary sources—and traditional materials feels historical but still of-the-moment. The exhibition brings the artist’s studio into the gallery space and revolves around her process creating the show’s centerpieces: large oil paintings. Interspersed throughout are studies by way of sculptural relief scenes, drawings, watercolors, and aquatint prints. Her clever use of space within each medium connects the techniques. Showing the smaller preliminary explorations of each theme alongside the final paintings is powerful.

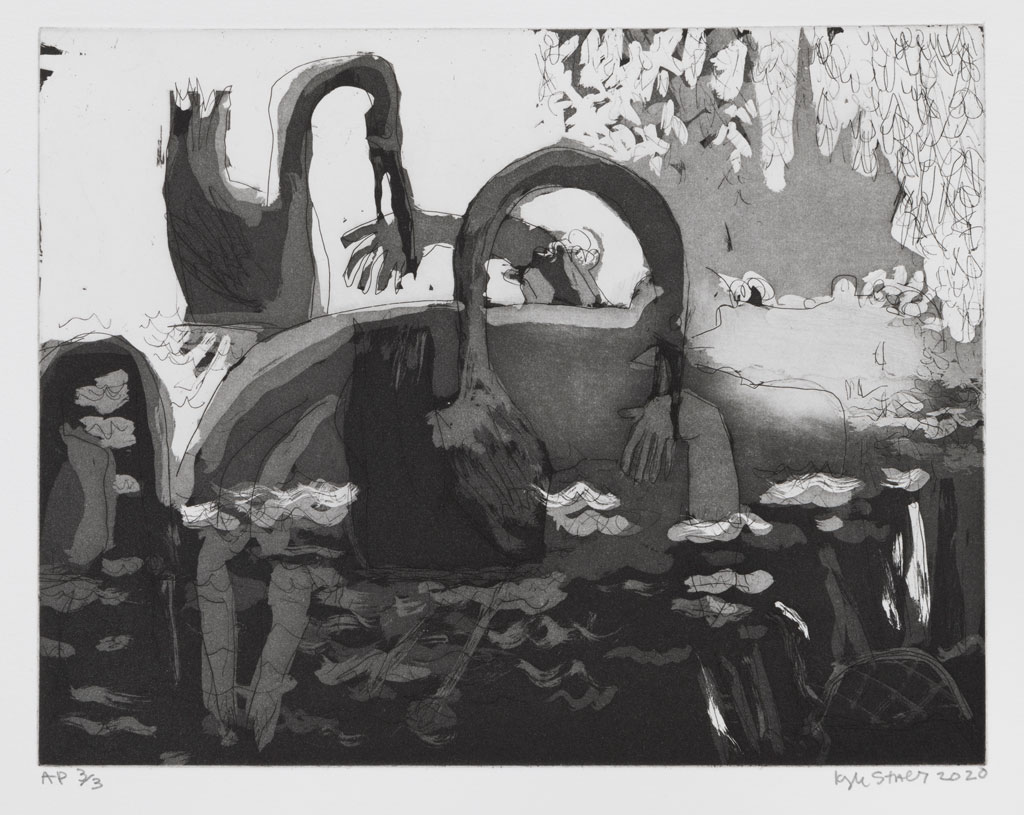

The drawings and etchings exemplify the urgency and fullness of the stories at hand. In Study for Medusa 1, 2020, for example, Staver presents a childlike ink and pencil drawing, full of squiggly lines and shapeless snakes squirming like sun rays around Medusa’s decapitated head. The aquatint etching print of the same subject, Study for Medusa, 2020, is almost identical in layout but the complex technique is less a sketch than a methodical creation. In their expressive and hasty qualities, both works provide a window into the artist’s modes of communication.

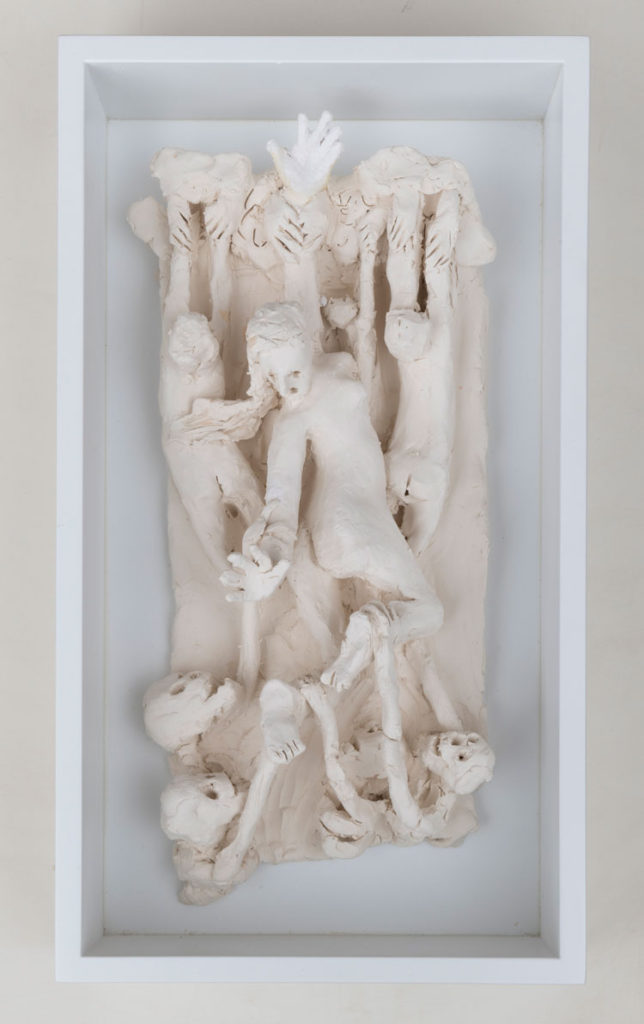

Alongside these studies are unpainted fired clay panels reminiscent of Renaissance church doors or classical temples, which replace sculptural precision with crude incisions and lumpy shapes. In Study for Death and the Maiden, 2020, a skeleton’s bony hands claw into a maiden’s flesh; their coarse faces and sunken eyes contribute a sense of immediacy, as though the artist was compelled to create the scene wholly without losing the story in the details. “The undulation of the relief can unite form and background,” sculptor Etienne Hajdu stated about the medium in 1953, “It also gives a spatial sensation without perspective; light makes its way across the surface little by little.” Staver’s reliefs have formidable depth and Hajdu’s sentiment resonates here. Staver layers the figures on top of each other; they are crowded, jumbled forms that meld together. Therefore, shadows play an essential role in establishing physical depth and definition.

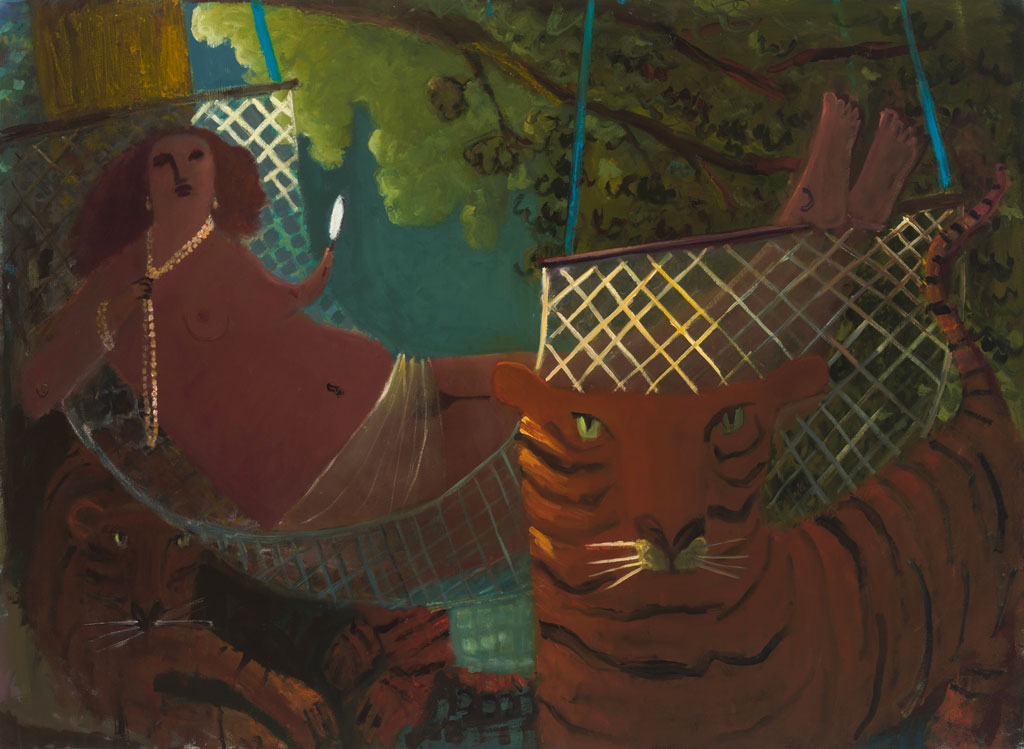

The large oil paintings are theatrical, vibrant, and primitive. They showcase the ease with which Staver plays with space. “When I make paintings,” the artist said in a 2016 interview, “I make them like a sculptor. I feel like I build them.”1 In Ophelia, 2020, for example, the familiar protagonist lies lifeless, her limp hand mirroring the elegant curves of the necks of three black swans swimming around her body. Ophelia’s blonde curls, the green glow of the canopy, and the birds’ bright orange beaks pop out of a dark palette, and in doing so contribute a subtle sense of three-dimensionality to the painting. The swans’ elongated forms and perky tails contradict Ophelia’s lifeless body in the center and frame her shape. A glowing soft backlight illuminates the shapes of the figures, while Ophelia’s head remains in the shadows before a background of cascading leaves that act as a green curtain behind the unfolding scene at center stage.

Similarly dramatic, a sense of upward momentum in paintings like Miss America, 2019, and Death and the Maiden, 2019, have an exuberant dimensionality that echoes the dynamism of the reliefs. In the past, Staver has explained her choice of size of canvas as a one-to-one ratio, and in that sense she composes the scenes as though we could enter the story ourselves. Legends and myths take on their own lives in her work, but they often share themes that work together to make sense of complex human behavior—love, despair, jealousy. They do this through entertainment and humor as well as revulsion and horror. Staver synthesizes various modes to investigate the possibilities of shape, line, shadow, and color to bring these stories into a contemporary and fresh perspective. Like Miss America, wearing a sparkly Americana costume as she triumphantly rides a bucking bull, the exhibition is enticing and alluring.

Kyle Staver is presented online by Zürcher Gallery.

Kathleen Hefty is a writer based in New York City. She covers art and culture for The Brooklyn Rail, Muse Magazine, and others.