During my childhood in Canton, Illinois, we had a gallery of eccentric gentlemen, but the prince of the group was Roger Heller. Clasping his raggedy overcoat with a rat trap, sleeping in the grass, surrounded by his pack of half-wild, canine attendants, and fascinating us urchins, his collecting expeditions were things apart. The man was obsessed with hoarding trash, especially paper, and scoured the town for it, accumulating it in great, noisy sweeps with a wheeled pushcart or a plywood plank roped round his waist, and storing it around one of the hovels he occupied.

These escapades, though, were only foils to his novelty, because much of the town—to this day, 45 years after his demise—think the man a genius: he could make crystal radios, speak Esperanto, explain atomic energy, and solve the high school mathematics problems students brought him. On occasion, he might saunter into a classroom to draw anatomical sagittal sections on the board, correctly labelled with medical terms, or audit the sermon from the last pew at the First Baptist Church. His habits found him now and then in court, where he always represented himself, and, while never legally acquitted, always acquitting himself admirably. Rumors of Heller’s intellectual achievements, generally self-planted, to be sure, circulated widely: he had invented radar; he had been to medical school; he spoke eight languages; he was married to a New York artist.

Following retirement from two years of government consultancy, itself succeeding a career of university professorships, I set myself the goal of discovering the truth about Roger Heller, and one of the first of a spectrum of revelations was that the rumor of his marriage had been correct. This was my introduction to Helen West Heller (ANA 1948), one of the finest woodcut artists America ever produced, who, by the time of my adolescence, anyway, was forgotten by her hometown; my hometown, Canton, Illinois, where her family moved in 1876 from nearby Rushville. I have since written extensively about her, including two books, and in 2016 co-curated Helen West Heller: The Art of a Prairie Child at the Birger Sandzén Memorial Gallery in Lindsborg, Kansas.

Born in October, possibly on the 9th—but that, only an allusion in a friend’s diary —in 1872, Hellen S. Barnhart grew up fiercely desiring a career in the arts: painting, literature, or sculpture—she was not particular at the time. For the eldest of four children with parents scrabbling to sustain them on a 10-acre orchard, this was a fond fantasy, but before she had finished high school, a family friend had staked her to two sessions at the St. Louis Academy of Fine Arts. She won a medal there in 1889 but claimed draftsmanship was all she had learned. That teacher deserved a medal, for she drew splendidly.

At the time of the Columbian Exposition in 1893, she tried her luck in Chicago but discovered a lack of it. “Starving” was an adjective she used with disconcerting frequency throughout her life, and this period was the first. Her nearest approach to her ambition was failing as an artist’s model, and the few known photos help understand why. Hers were neither a pre-possessing physiognomy nor physique. The Little Engine that Could did not fall back to the orchard, however; characteristically, she set her sights higher and moved on to New York City.

There she met two husbands and caused her first ripples in the wide ocean of the arts: a poem and accompanying drawing by Helena Barnhart appeared in Criterion in 1899. She married interior decorator (paperhanger) Herbert West in 1901, and as Helena Barnhart-West showed in bookbinding and illumination at the 1902 exhibition of the Architectural League of New York. She never lost the talent for rendering heartwarming depictions of children.

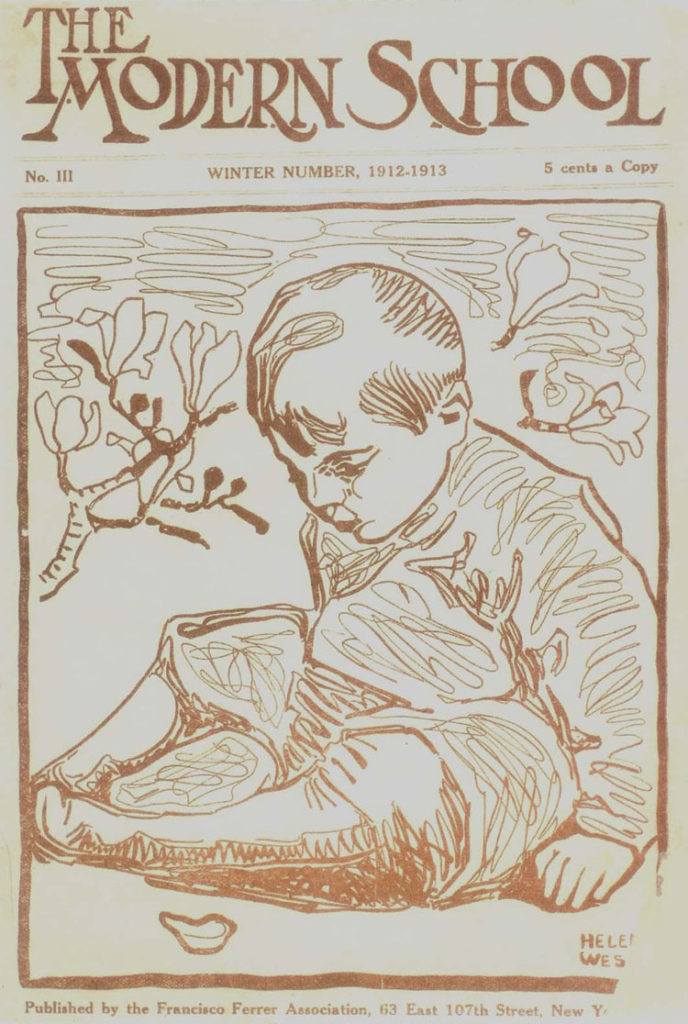

In 1905, she separated from West. Not later than the winter of 1911 – 1912, she appeared at the anarchist Ferrer Center and Modern School. The attraction probably was not ideological, but cheap instruction by the likes of George Wesley Bellows (NA 1909; NA 1913) and Robert Henri (NA 1905; NA 1906), the latter of whom she disparaged in a May 18, 1946, letter to Helen Voss Brinck: “Robert Henri, whom I contacted many years later, was openly jealous of my work and blatantly discriminated against it, and once I heard him declare that he had no reason to wish that we would be successful. He was a not-so-rugged individualist.” Leon Trotsky, Man Ray, the Zorachs, Ben Benn (ANA 1980), and Rockwell Kent (ANA 1948; NA 1966) were among her fellow students, and the school magazine used her drawing for its winter 1912 – 1913 cover.

At Ferrer she also met Roger Heller, 16 years her junior, scion of an affluent family, electrical engineering honor graduate of Lehigh University, and yet discharged in rapid succession from his first three professional positions. If one radicalized the other, the young Esperanto aficionado was likely the one, but the artist surpassed him in left-wing activism for the remainder of her days.

After a pause in Allentown, Pennsylvania, for a stretch of socialist propagandizing, a nationally publicized arrest for boarding house theft1, and self-marriage under Pennsylvania law, she took her new prize back to the family farm. There she slaved, she wrote, to help her father, while her husband engaged in what he described as linguistic research.

Between and after chores, the new Mrs. Heller found time to publish several poems in reputable literary magazines and, by means of fine-line watercolors, illustrated three volumes of poetry by Edwin O. Grover, Madison Cawein, and W. Nesbit, respectively. When her husband demurred at turning his time to remunerative effort, she abandoned him and set out for Chicago, where she hoped to secure an exhibition at the Art Institute. They promptly rejected all the paintings she submitted, which propelled her into her next phase as a well-publicized fixture among Chicago’s independent—meaning rusticated—artists.

One of art history’s benign events came in 1923, the year she was 51, when Helen West Heller carved her first, bona fide woodblock—it became a magazine cover, she wrote, but of that there is no trace—and her skill and innovation escalated rapidly for nearly three decades.

During 1925 – 1927 she had a near-weekly, unpaid poetry column called “Tanka,” after the Japanese form, in the Chicago Evening Post. The paper also printed her own articles on art topics and provided her many candent reviews of her exhibitions, style, and individual pictures. Her May 26, 1925, contribution is entitled “Artist’s Life,” and reads:

When she was a child

Her mother refused for her

Invitations to

Parties because she did not

Have shoes. A woman, she

must

Send declinations

To weekends, for the lack

Of car fare

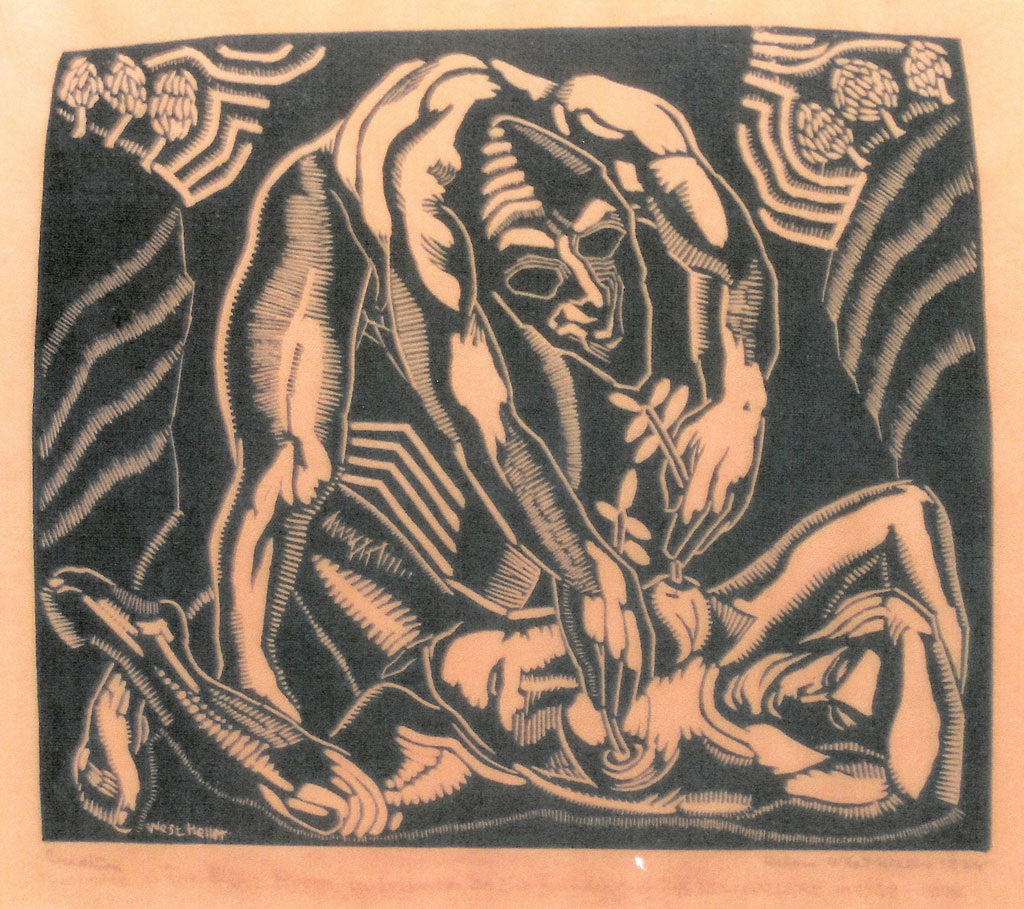

She had exhibitions; was shown in Paris, Vienna, and London; and sold paintings and woodcuts; but, alas! not in numbers to provide any semblance of comfort. In 12 years in Chicago, she inhabited nine different addresses. At the time, her sex and her Modernism were marks against her, and frightened critics failed to enhance her popularity. About her 1930 linocut, Creation, Eleanor Jewett wrote in the Chicago Daily Tribune, that it “smacks enough of the vampire, ghoul, and mad nightmares to make chills run up and down the spine.”2

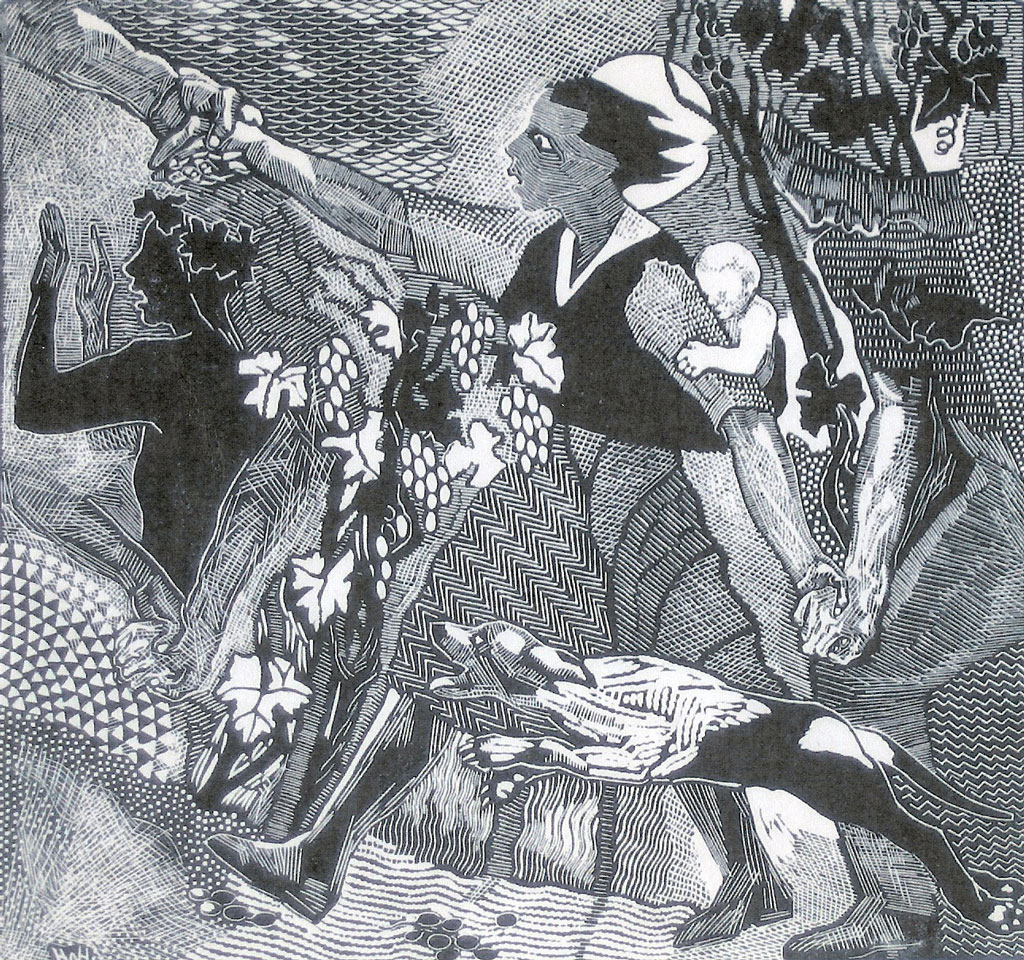

For all its terror, Creation carries the germ of her trademark: the rather modest but brilliant usage of disparate patterns mostly as a means of embellishment. Its offspring would be plentiful.

In 1928, she published her first all-woodcut book, Migratory Urge, fragments of which are now housed in the permanent collections of organizations such as the Brooklyn Museum, the New York Public Library, and The Metropolitan Museum of Art. The book showcased a selection of her poems—all incised into woodblocks—with each accompanied by a simple illustration in what was already her best medium. As long as she lived, though, she thought and wrote of herself as primarily a painter. All 109 copies sold, and garnered but a single, unemotional, local review; along with much of what she did, the book passed into obscurity.

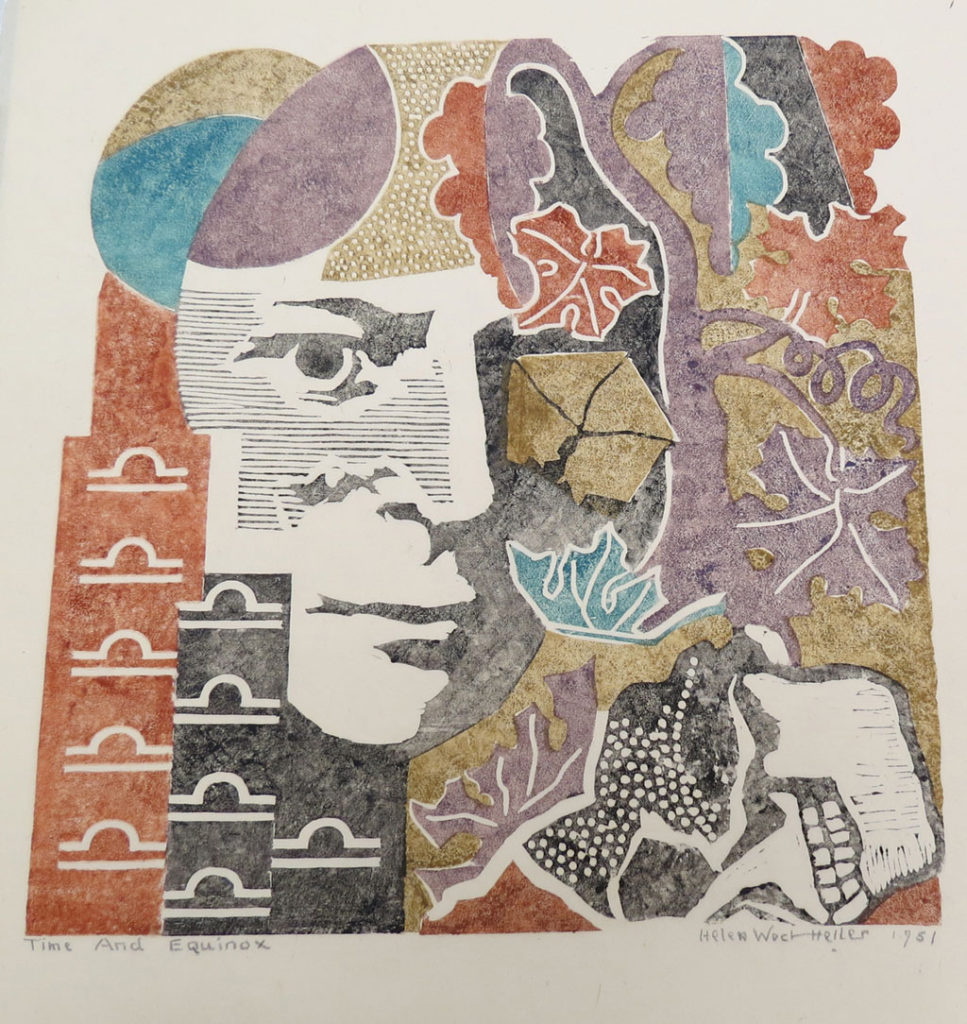

Critics described her color sense, and on that subject she wrote essays, articulate and profound for so little formal learning, from both historical and modern theoretical points of view. Few paintings survive for consideration, likely an implication of past opinions of their value. Black and white newspaper reproductions of them are repellant, and whereas she often used the same general scene for both a painting and a woodcut, the latter are always superior. In fact, she used oils as preliminary studies for the more precise prints.

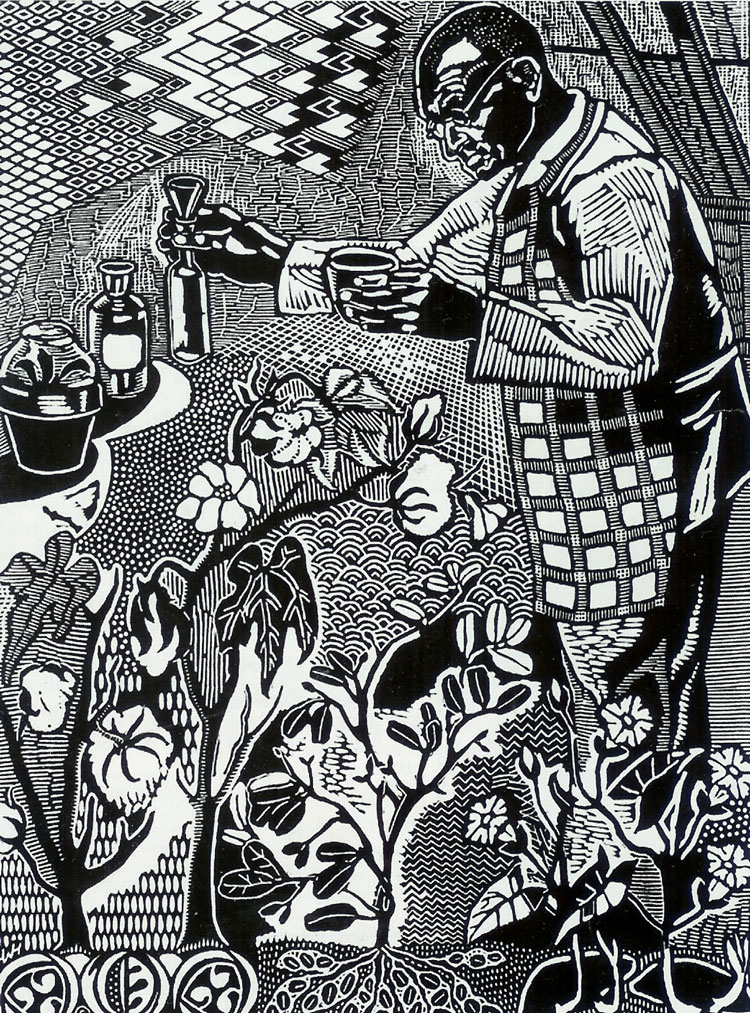

Every picture asks at least one question, poses some problem that often defies resolution, and interrogates viewers. If the action itself fails to cast a mystery, mere facial expressions and details may. “Why should a fellow planting trees look so cunning?” “Who is the architect with triune heads, and what is he designing?” “What exactly is the playful cat interrupting?”

Into a small rectangle of paper, she could fit entire industrial processes, set the foundations for a science, encapsulate civil defense systems, and highlight the career of a person, such as George Washington Carver in Alabama Biochemist, 1947.

She could invest immotile settings with motion, and her design approach helps account for that. Whereas a detailed drawing traced onto a block was the starting point for the typical artist, Heller considered those de facto copies; she sketched only the major constituents of a design, and accomplished much of the composition in the wood, where the margin for error was slim. This spontaneity imparted a natural dynamic to her pictures. She agonized over the declining quality of paper obtainable and never resorted to a press; each print was carefully hand-rubbed with a stick.

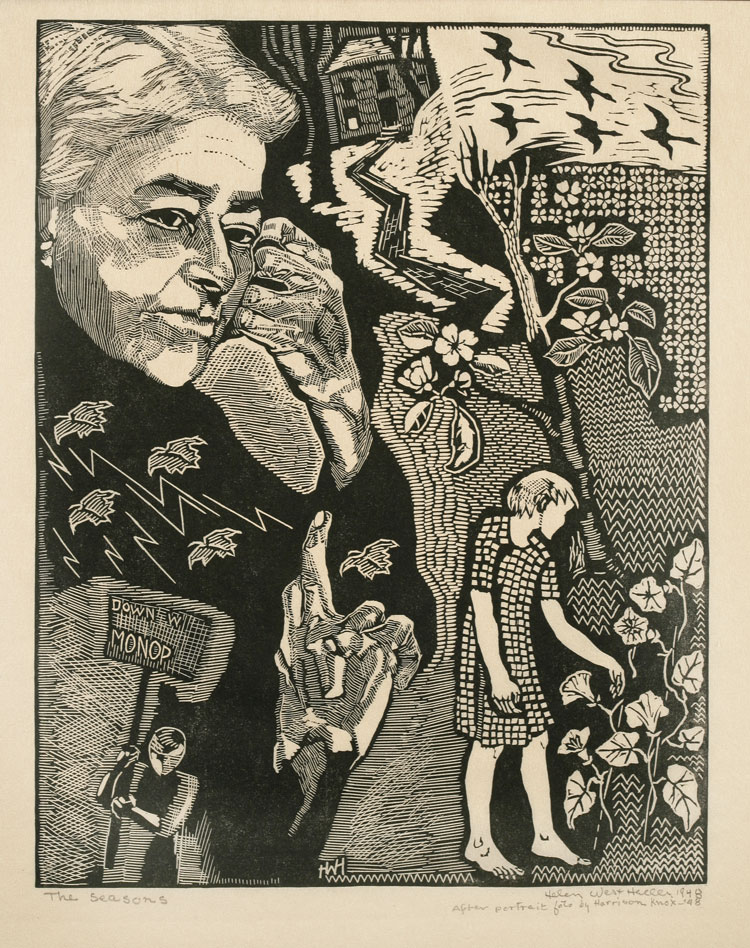

For centuries, her predecessors had approached the problems of color and texture representation with tactics like cross-hatching and cuts of varying widths, but Heller brought her ingenious use of repetitive patterns. Like the structure of matter itself, she was able to synthesize objects from aggregates of design molecules, sometimes chosen for relevance to the particular theme, as were the little flower blossoms in the self-portrait she created for the National Academy of Design when she was elected as Associate National Academician. For this submission, she gave a good portion of her life and not a little of her spirit.

She learned even to materialize her objects and concepts, like a subject in a painting by Thomas Wilmer Dewing (ANA 1887; NA 1888), emerging from a background of tiny atomies. And what a spectrum of questions those atomies ask in Flight, 1951.

In favor of New York again, she broke from Chicago without brass in February, 1932, and only one newspaper item, anonymous and published in her wake, lamented the loss.

In terms of revenue, the new pasture was not significantly greener—she wrote to a Chicago paper that New York’s advantage lay in a greater number of galleries to reject one’s work, therefore decreasing the probability of death in the streets. As she grazed there, however, her woodcutting prowess burgeoned.

In 1934, she met a flamboyant character named Onya la Tour, a Catholic-in-waiting Communist, gallery and museum owner, rather an artist groupie, and known for her extra-marital affairs, who promoted Heller’s work. A scrupulous diarist and scrap paper collector—grocery lists, for example; her observation penetrates the poor orthography to give insights into the artist’s life and habits. La Tour commented that incense over Daily Worker articles was washing out Heller’s paintings and that she had a knack for making herself appear always worse off than oneself.

Though Heller groused that her admission had been intentionally delayed, the Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration provided some pecuniary relief. She received generally about $90/month in wages for six years, from 1935 – 1941. For its investment, the government received a hospital mural; designs for a subway mural, of which the program was scrapped before execution; several masterful woodcuts; and detailed sketches to accompany a Johnny Appleseed mural proposal that was rejected.

In January, 1935, Heller was blessed with the start of a 20-year friendship with Helen Voss Brinck, 38 years her junior; a person who remained a staunch and tangibly helpful friend, even through her own marriage and maternity, and despite the sometimes-rancorous ways of the aging artist. The two produced a rich correspondence, in the letters and essays of which are found accounts of Heller’s everyday existence, along with her artistic ideals, personal suffering, and political philosophies.

The reception for the largest of her Federal Art Project pieces, what might be termed a modular mural, was held at the now-abandoned Neponsit Beach Hospital in Queens, New York, at the place of installation.

The 1940s saw Heller winning firsts in Library of Congress competitions and the appearance in 1947 of her second book, Woodcuts, U.S.A. Even in her successes, though, were seeds of disappointment. After the Smithsonian’s 1948 retrospective of her pictures, she wrote Director A. Remington Kellogg and implored him to purchase a suite of her designs; the institution bought one. When the National Academy of Design included her as an Associate that same year, she expected eventual full membership; the fact that she never was elevated stung and embittered her the remainder of her life.

This present article, in fact, is a fortuitous consequence of that disappointment and of her lack of advancement through succeeding years. I broached the subject with the Academy, advocating for her posthumous full membership, but learned this was not possible because such honors can only be bestowed during the life of an artist or architect, as decided by contemporary peers. However, these discussions served to bring her to the attention of the National Academician Membership Committee and staff and invited the present contribution.

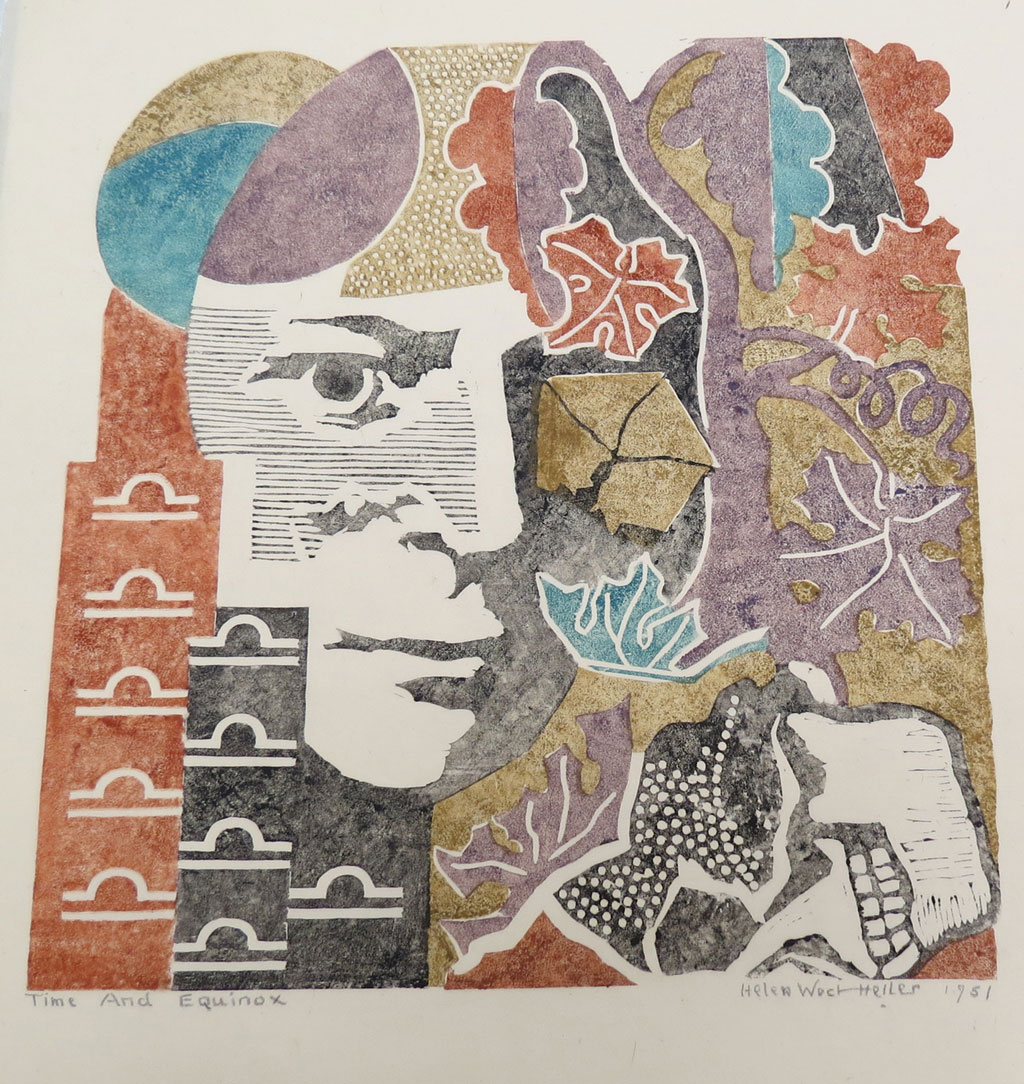

Eleven Symbolist and mystical color scenes—at 17 in. x 17 in., very large for her—executed between 1951 and 1952, mark her final love affair with woodblock printing. Never slow to complain, she acknowledged that these sold well, but according to a pattern that must make her smile from somewhere, surviving copies are scarce.

Unjustly, there was not a great deal to her in life; less, of course, in death, which collected her at Bellevue Hospital on November 19, 1955, after she had lain stricken and alone for a day. Her artifacts, confined in her two rooms at 732 East Sixth Street, were likewise meager.

For two years she had informed correspondents of the tiring work of assembling six full, indexed sets of her prints, and even assigned them to individuals. A May 22, 1955, letter to Helen Garlinghouse (née Voss Brinck) stipulated that number 1 was to remain with the artist forever; that 2 and 3 were earmarked for (unidentified) individuals; that 4 was for her friend, Fanny Ress; and that 5 might be entrusted to the addressee—if she paid the artist a visit. Number 6 was unattributed. Further, all the woodblocks were there, she remarked; yet all these treasures have vanished. The only vaporous trace is found in a May 17, 1956, letter from her friend Dr. Ernst Harms to a member of her Memorial Committee, Fanny Ress’s husband, attorney S. Michael Ress, implicating him and his wife in the immolation of Heller’s papers in the building’s furnace.

Her hometown noticed her passing 12 days after with 11 lines of obituary mostly devoted to the temporary disappearance of her estranged husband, Robert Heller, in transit to claim her body, which had been interred in a charity grave in New Jersey before his arrival. He had remarked that death obviated haste and that he first would visit Chicago museums.

Neither had her decline played in softer lights: an end to publicity and exhibitions, meager subsistence from the Artists Equity and New York City government relief, and neglect by acquaintances. In her mind, conspiracies, gang-ups, thefts of ideas, and clandestine attacks had crippled and stunted her career. She had harsh words for nearly everyone she had known, including some that had championed her; she even managed to alienate Helen Garlinghouse, that self-sacrificing friend of two decades.

What a dismal conclusion to the woman called by C. J. Bulliet, Arts Editor of the Chicago Evening Post, in 1931, “the foremost master of the woodcut in America and a fifty-fifty bet the superior of anyone in England, where woodcutting was supreme.”3 At that date, Heller was an ingenue in her art; one wonders if his vocabulary would have sufficed two decades later.

With a Ph.D. from Northwestern University, Larry Stanfel was a member of several university faculties, including the University of Florida, Colorado State University, and the University of Texas, and a consultant to government agencies and private organizations. The author or editor of six books and numerous articles in periodicals, and twice the recipient of post-doctoral research fellowships, Stanfel’s books on Helen West Heller constitute her most definitive and comprehensive biographies. They are Uncompromising Souls: The Lives and Work of Artist Helen West Heller and Husband Roger and The Complete Poetry of Helen West Heller: With Illustrations Selected from Her Art. He lives with his artist wife, Jane, on a small ranch northeast of Roundup, Montana, from which they presently collaborate on weekly articles on historic aspects of Montana for the Roundup Record Tribune.