The National Academy of Design recently welcomed its newest class of National Academicians, 15 extraordinary artists and architects who join a community dating back to the founding of the NAD in 1825. Learn about the election process and watch the induction ceremony here.

As part of the celebrations, the NAD’s newly appointed executive director Gregory Wessner interviewed each of the incoming members to talk about their work and ideas, and how the upheavals of the past year have affected their practices. Conversations will be released throughout the coming months. This interview took place on November 11, 2020.

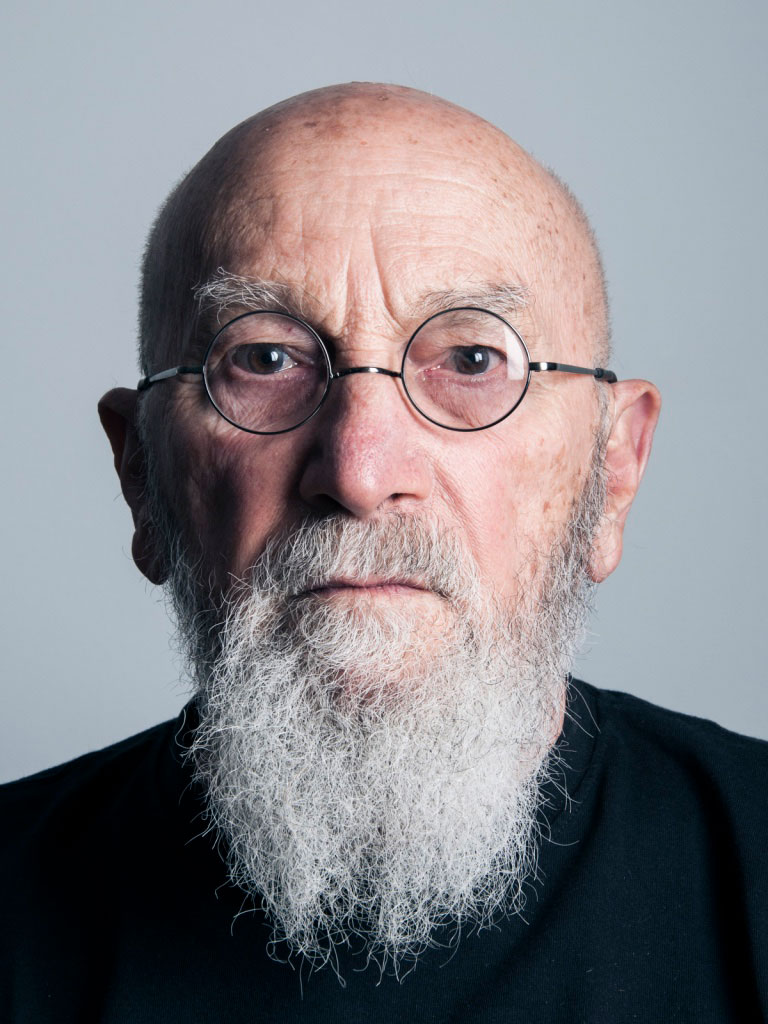

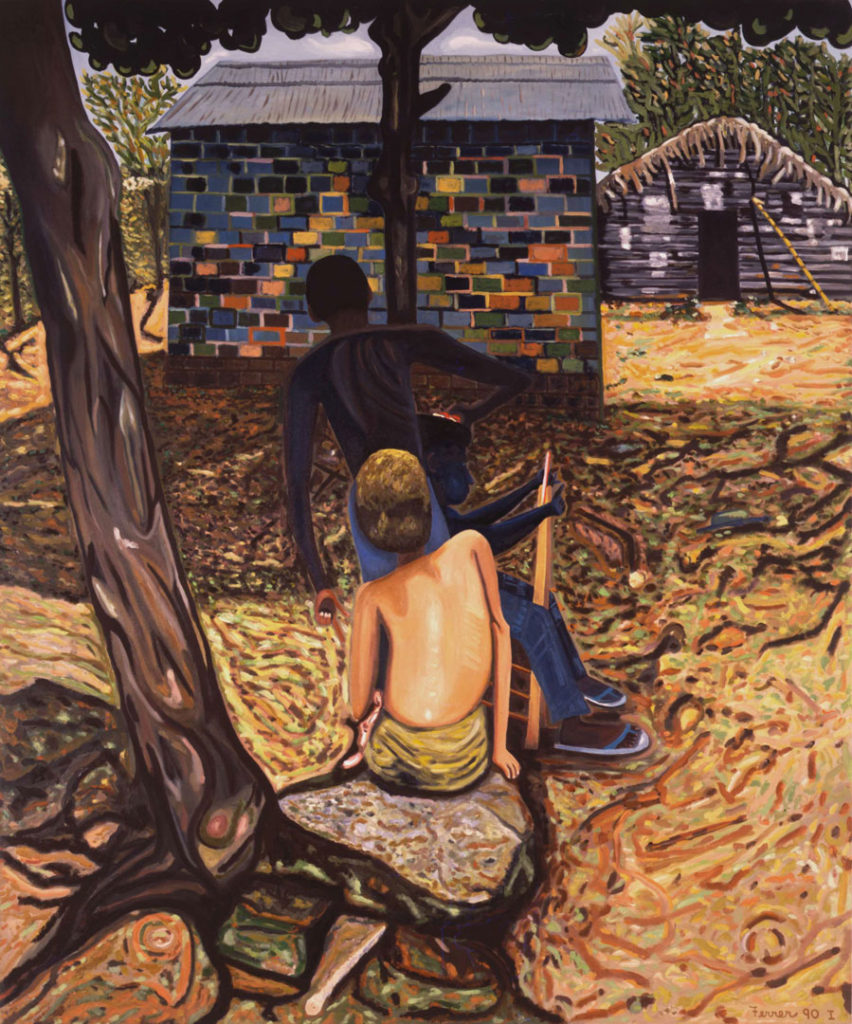

Rafael Ferrer (NA 2020) is a Puerto Rican artist who lives and works in Long Island, New York, and Vieques, Puerto Rico. He began his career as a musician, developing an improvisational style that carried through into his visual art. As an artist, Ferrer is predominantly self-taught, and his works include paintings, drawings, sculptures, and installations. In this interview marking his induction, Ferrer discusses transitioning from music into visual art; his relationship with his half-brother, actor José Ferrer; and how he learned to paint outside of a traditional classroom setting.

Gregory Wessner: When I was preparing for this conversation, I saw that you lived for quite a while in Philadelphia. I was born in Philly.

Rafael Ferrer: I lived in Philadelphia for 26 years. It’s a fascinating place. Right off the bat, I’ll tell you, after being there less than a year, I realized that Philadelphia was exactly like San Juan, Puerto Rico, where I was born. They both saw the future through a rear-view mirror, as if everything important had already happened. Ironically, it had many outstanding, passionate 20th-century collectors, including Albert Barnes, Lally Lloyd, Paul and Hope Makler, and Henry McIlhenny. I probably spent more time on the New Jersey Turnpike than anywhere.

Ah, the Jersey Turnpike. Yes, I know it well. So let’s talk about growing up in Puerto Rico.

My grandmother was from Asturias in Spain, from Gijón. She had had four daughters, three of them had been born in Spain. Her husband was in the import/export business with headquarters in Puerto Rico. In his late 40s, while dying of pneumonia, he asked her to bring his daughters back to “America.” So, as a pregnant widow, she moved to the only place she knew in “America”—Puerto Rico. That’s how my mother’s reality developed. The problem with my mother and her four sisters developed from being brought up by a single mother who came from a very old culture. So the only way that she thought she could control these five girls while they were growing up was by instilling fear in them. And it definitely created a brood of five very strange ladies, my mother being the queen of them all.

Alright, so the question then is: Did you inherit any of that strangeness?

[Laughs] No, though I did inherit the power of my grandmother. What can I say? My grandmother, well, I was her first grandson. I think it’ll interest you to know that while I was growing up, my grandmother had two guest houses or Casas de Huesperes, what the French call “Pension de Famille,” where people lived and ate their meals. Living at my grandmother’s were exiles from the Spanish Civil War, seeking refuge in a Spanish-run establishment, many of them luminaries from the Republican defeat. So I grew up as a kid knowing Pedro Salinas, and as a teenager, I had conversations with the poet, Juan Ramón Jiménez, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1956. This environment really was the thing that was feeding me in terms of what I would do and what I would become. In a certain way, that’s probably responsible for the fact that I trust learning on my own, being self-taught, more than I’ve ever trusted any diploma. I don’t have any diplomas, except from high school of course, Staunton Military Academy, in Virginia. Which did teach me discipline, as well as not wanting to ever again be a member of a group, or join anything. I mean, I love that story about how Groucho Marx didn’t want to join a club that would accept him as a member.

Wait, how did you end up in a military academy in Virginia?

There was a lot of difficulty with my mother’s psychological condition, and everybody who cared about me, especially my father, thought that I would be better off living in the States. I had the good fortune of having a half-brother living in New York, José Ferrer, who was 22 years older than me and a great actor in the theater.

I spent my vacations while at Staunton Military with him and his second wife, Phyllis Hill. It was a period that was glorious for me because he generously shared so much with me. I don’t think he ever realized how much he taught me.

You are known for drawing inspiration and references from all over the place. Was there anything from your half-brother, in terms of the craft of acting, that you drew from?

Well, my brother did love jazz and had many professional musicians as friends, so he would take me to clubs in New York where I always paid the most attention to the drummer of the band. That was my first, real passion: playing music. Being a musician is hard to describe because my life has been defined by what I’ve done as an artist, and not as a musician. But I have never had a moment in visual art that rivals the exuberance that one gets when everybody in a room is grooving to music, paying attention to what was going on. It’s so exhilarating that you never forget it, it’s almost like a dream.

In the studio, it’s you and a work, and you can be in a moment and be fully engaged with what you’re doing, but it’s ultimately you alone. Whereas when you’re with a band, playing with other people, there’s a sense of community when you’re all jelling.

Yes, yes, yes. It’s like being on a tightrope and everybody is doing everything right so nobody falls off. I’ve heard people say, “Drummers lack eloquence.” I say, “If you find punctuation an inferior activity, then you don’t know what you’re talking about.” Drummers are not supposed to interfere. That’s why I’ve always hated drummers who are considered stars—they’re essentially showoffs. Whereas the best percussion is the structure that the other musicians play around. My brother always said that he never saw me beaming when I met Lawrence Olivier, David Niven, or other famous actors when they came back to his dressing room after a performance. But I did on the day that Buddy Rich came in. At the end of the day, my career in music was a real disenchantment.

This is funny because recently I interviewed Charles Gaines (NA 2020) for this same series and both of you are artists who worked as musicians, and not only that, but as percussionists. And both of you were searching for ways to combine these two passions. Would you say that being a percussionist had an impact on your work as an artist?

I formed a little group at Syracuse, we played weekends at a local nightclub. I got the other guys to play in the band because Billy Rubinstein, the pianist, was famous. He was amazing and the nicest person. I was the youngest and most ignorant of all the musicians in my group. Through him, I met graduate students in literature, painting, and other fields who became my friends.

One day, I said to a guy who was studying painting, “Listen, I’d like to know what is going on.” He said, “Oh, great. I’ll bring a book.” It’s an old Skira book, which I have now, called From Picasso to Surrealism. We sat at a table and went page by page. I would point to a particular painting and say, “Okay, so this, wow. Why did they do that?” We went through it just like that. Out of just that event, I went and bought painting materials. I used the cardboard you get back from dry cleaners with your shirts. And I began to paint on them.

Then, this friend of mine said, “I want to see what you’re doing.” I showed them to him, and he said, “This is great. I want to show them to my teacher at the college.” So we went to his night class. The instructor took us outside the classroom to the hallway where we talked, and then he looked at my work. I said, “Do you think that I should take some lessons?” He answered, absolutely dead serious, “No, I don’t think so. I think you’re doing something that you may lose if you do.”

“That is something that you might lose if you go study,” is what he said.

That’s it. That is it, Gregory. That is the explanation. And the thing is, I’m a voracious individual, meaning I look everywhere; I read everything. My library has more money invested in it than I have in art supplies. That’s been my learning process.

In music, when you listen to Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk, Charlie Parker, or Bud Powell, you see them doing things that no one has heard before, but they will also throw in a quote from somebody else. When you teach yourself—to paraphrase Louis Kahn (ANA 1965): “I have no hope for my students. I only have hope for myself.” You learn because you need that knowledge, and when you need it is when it becomes relevant to you. The thing I learned was that all the great painters who are remembered, even before Titian, all learned from other artists. That is the natural course. Now it’s a diploma that makes you what you are or defines you. And this is why I know I do not belong, it is something anathema to who I am and what motivates me.

This is also a rough explanation of how I’ve come to recognize myself as a person who is fundamentally Spanish. It is as if, having grown up in a colonial culture, overridden by the Americans, I have had to set myself free, to function again in that tradition. Americans think it’s a misanthropic thing or that you’re a weirdo. No, I’m not a weirdo. Some days I don’t even like myself. That’s something a Spaniard would say.

The ultimate misanthrope, you can’t even stand yourself.

Right, exactly. Yet, within that tradition, there’s a great tradition of wit and improvisation. I always blow people away when I recount this story: There are two eminences in Madrid. Both are famous writers who detest each other. One day, they find each other walking on the sidewalk of a narrow street, in opposite directions, one coming, the other going. When they pass each other, one touches the corner of his hat. The other says, ‘I don’t greet sons of bitches.’ The one who touched his hat says, ‘I do.’”

That’s great! I want to circle back to something you said earlier. You never studied painting? You just started painting one day?

Or rather, let me say, I have never stopped studying painting. What I did not do was sit down in a classroom, listen to people who could not paint themselves out of a paper bag, telling others what art is.

The main message we see in art schools now is, “The future is networking.” But networking, what is that? Is it like the blind leading the blind or misery likes company?

Since you brought up networking, I want to quote something you said back to you, which is that, “Networking is just a flimflam word for suck ass.”

I don’t know if I said flimflam because that’s a very American word.

[Laughs] But the suck ass part?

Yeah, that’s right on.

The way I read that quote in context, it had to do with the art world, and how it pushes artists into a certain way of working. Because it is also a market and an economic system that values consistency. They want you to become a producer.

The unbridled power of capitalism has devoured everything by turning everything into a product. Believe me, Gregory, I am not in any way a person who spends time worrying about these things. But what I can tell you is that when I became an artist, I could go to every gallery in New York City in one day and have time to go to a museum. Leo Castelli was an incredible individual. But before he died, he said, “The future will lie with Gagosian.” I’m not going to put the blame on any one person. I mean, it’s not Gagosian Gallery alone—it’s four or five galleries. They’ve taken over the whole scene. They can create a superstar by going to a village in Venezuela, bringing him and his whole family, putting them up at the Ritz in London, and declaring, “This is it.”

Early on, Robert Morris (NA 2006) said to me, “New York criticism is about guilt and innocence. Either you’re guilty or you’re innocent.” I can’t give you examples right now, but I realized that it was true. The manipulation going on for a long time now is something for economists to analyze. I read one who commented that the art market was the last unregulated industry where you could play games that would be totally illegal in any other industry.

What can I tell you? Listen, I am very happy with my life. One day, I’m not going to wake up and it’s going to be fine, but I am not in the industry of preserving a future. If I’m lucky, someone will look at my work again, but I am not going to spend time worrying about it. Right now, we have a pandemic, and this dictator who is President creating havoc daily. So what do I do? Instead of sitting on a sofa, watching the news, I go to my studio. I have two seven-foot paintings I’m working on right now. I’m doing them because they cannot be taken out of the studio. They don’t fit through the door.

I’m not here crying or complaining. You’re talking to a calm person able to function at 87, in the middle of this horror story. People believe that the art world is going to come back just like it was. It can’t. There are too many parts that are built on questionable premises. They won’t hold up under the pressures of this new reality. Nothing is exempt.

Has your time in the studio changed during the pandemic?

No. I go every day, the same way, my wife can tell you. I have breakfast and then I’ll go to the studio. I’ll sit down and read something first and then I immediately get energy from that and go on. For instance, Cézanne is more alive than anybody that I know right now. The most terrific thing that I have seen in art is something that is not finished. Why is it that every time you look at Les Demoiselles D’Avignon, you feel you’ve never seen it before? The reason why is because it’s unfinished—it has that element. This is what a school will kill because they want a product, and products used to be only things like Ford cars and Kodak cameras. Now everything is a product.

Okay, one last question. I’ve been thinking a lot lately about the National Academy as an artist-run organization, and the role of artists in a moment like this that we’re living in. What do you think? What role do artists have to play right now?

What I really think, honestly, Gregory, is that we’re in such a flux moment. It’s not just the pandemic, it’s the political situation worldwide. This is a historical moment. I grew up affected by the Spanish Civil War. I saw the exiles and I heard their stories. The person that essentially turned me onto art in a more literary sense was a Spanish surrealist named Eugenio Fernández Granell, who escaped to France over the Pyrenees. Through him, I met André Breton, Wilfredo Lam, Benjamin Péret, and many of his friends in Paris in 1954. What Granell gave me was the knowledge that there is a treasonous element within any movement that is capable of eventually destroying itself. This is a guy who belonged to Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista (POUM), the most leftist of all the groups that were fighting the fascists in the Spanish Civil War. Ironically, the POUM was selected by Stalin to infiltrate and destroy the Spanish Communist Party because Stalin did not want another socialist movement to rise.

When I met Granell, I was 20. He was maybe in his late 40s. He had been in the war and seen people die around him. They were going to kill him, not only in Spain, but wherever he fled, which happened to be the same places the French Surrealists fled to when Adolf Hitler invaded France—the Dominican Republic, Mexico, and countries in South America. Eventually, some came to Puerto Rico. By that time, Granell was totally embittered about the whole situation. He said something to me that sounds horrible: “Ferrer,” he never called me Rafael, “If you are in a situation where everything is in play, the first people you’ve got to get rid of are the liberals because they’re going to sink you. They’re the ones that are going to turn on you and make you the victim.” That has replayed over and over in history. Just this morning, speaking with my wife, I said, “If Joe Biden now wants to replay Barack Obama’s acquiescence to the unyielding opposition and play fair, he will fail. Allowing all these horrors, done to undermine and destroy what democracy is left—to let it go completely unpunished and turn the other cheek—would be criminal. How many more cheeks do we have to turn?” It’s grim, Gregory, but I can’t tell you how wonderful it’s been talking to you. It’s been a real pleasure.

The National Academy of Design welcomed Rafael Ferrer, along with Derrick Adams, Cecily Brown, Enrique Chagoya, Mitch Epstein, Beverly Fishman, Charles Gaines, Carmen Herrera, Michael Maltzan, Toshiko Mori, Jennifer Packer, Walid Raad, Betye Saar, Beverly Semmes, and Claire Weisz as National Academicians on October 28, 2020.

Gregory Wessner is the Executive Director of the National Academy of Design. Previously, he served as Executive Director of Open House New York, and has also worked at the Architectural League of New York, the former National Academy of Design School of Fine Arts, the Parrish Art Museum, and White Columns. In recognition of his contributions to art and culture in New York City, Wessner recently received the Award of Merit from the American Institute of Architects New York. Wessner did doctoral research in art and architectural history at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York and completed undergraduate studies in Art History at Rutgers University.

Rafael Ferrer (NA 2020), born 1933, San Juan, Puerto Rico, lives in Greenport, New York.

Ferrer began as a professional Afro-Cuban drummer in New York. His important early influences were artists and writers exiled in Puerto Rico from the Spanish Civil War and artists he met in 1950s Paris.

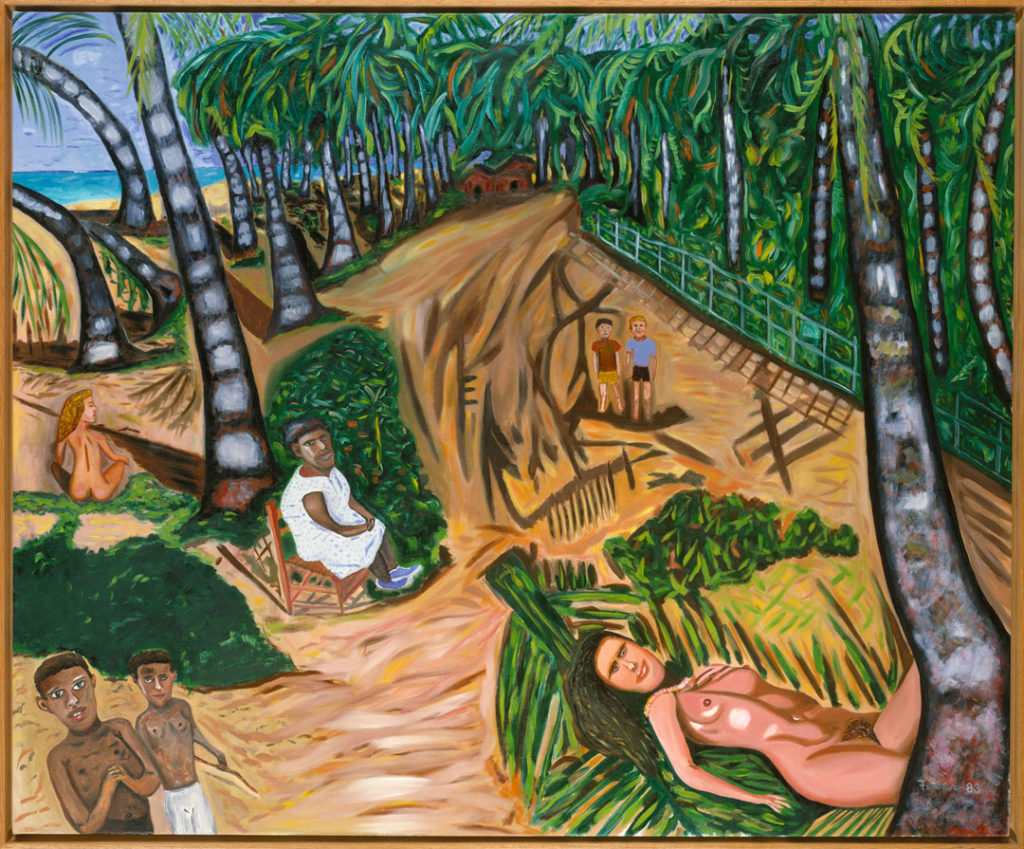

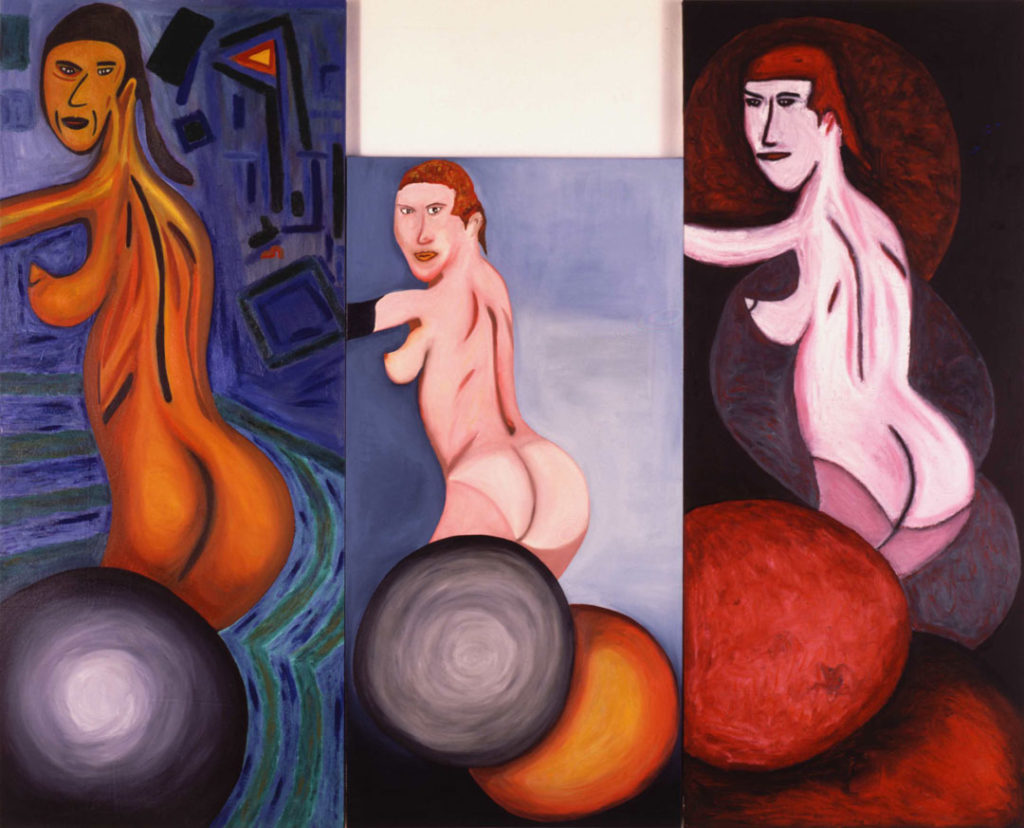

First known for his 1960s engagement with the first wave of Conceptual and Post-Minimal artists in New York, his work progressed by the 1970s to a more personal practice. His installations transformed into emotionally packed environments, referencing actual places, introducing identifiable objects, and giving meaning to his materials. Eventually leading back to painting and Constructivist sculpture, both ways to continue improvising his subject matter.

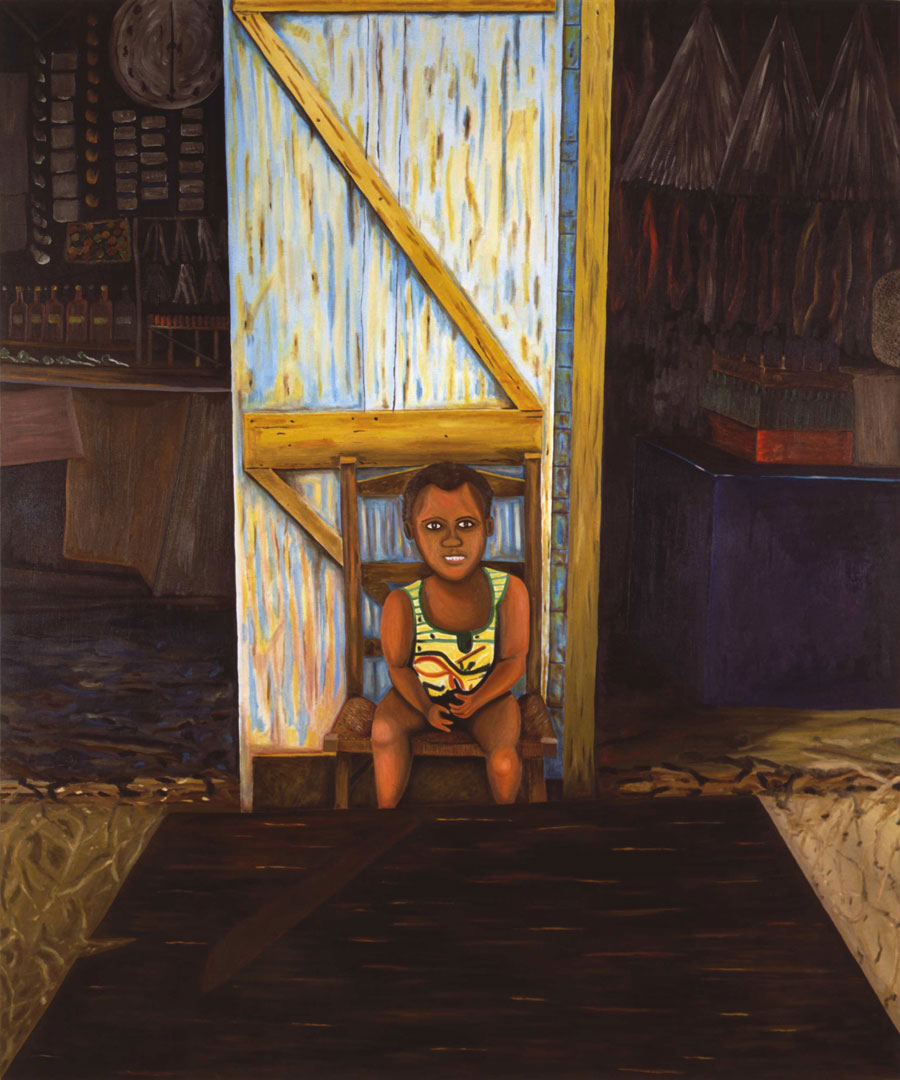

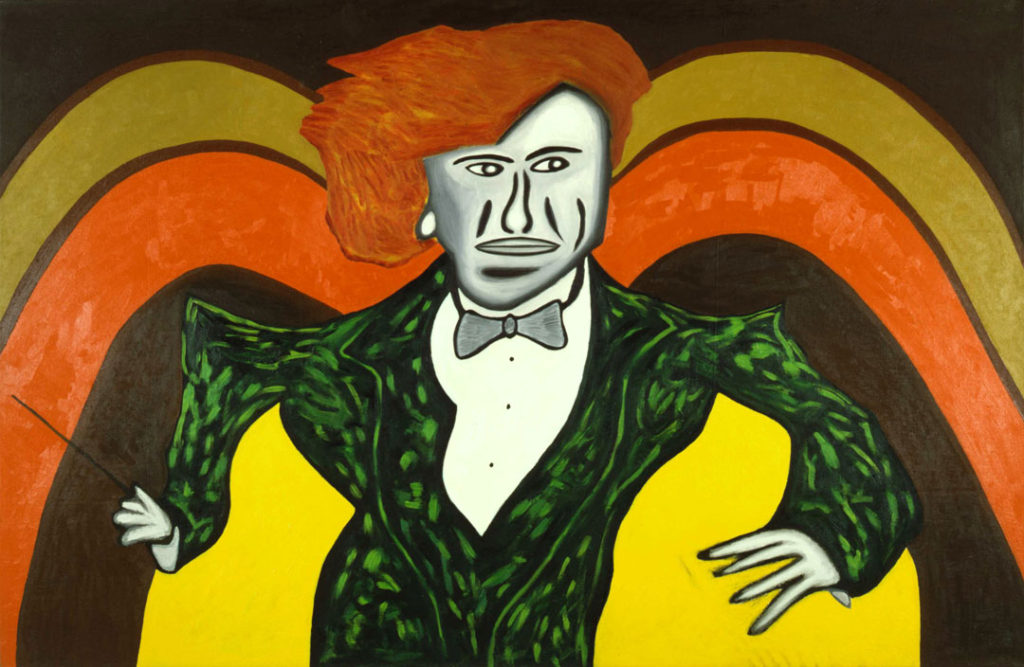

Header image: Rafael Ferrer, El Principio, 1992. Oil on canvas, 72 x 60 in. © 2021 Rafael Ferrer / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY