The National Academy of Design welcomed its newest class of National Academicians last fall, 15 extraordinary artists and architects who join a community dating back to the founding of the National Academy in 1825. Learn about the election process and watch the induction ceremony here.

As part of the celebrations, the Academy’s recently appointed executive director Gregory Wessner interviewed incoming members about their work and ideas, and how the upheavals of the past year have affected their practices.

Mitch Epstein (NA 2020) is a photographer whose work explores social issues and questions what it means to be American. He started making photographs when he was in high school and helped pioneer fine-art color photography in the 1970s. His projects include American Power, which examined how energy is produced and used in the United States; Family Business, which traced the demise of his father’s furniture store; and most recently, Property Rights, which looks at communities around the United States fighting for their lands. Here, he discusses how traveling abroad early in his career changed his perspective, his use of research to guide each project’s direction, and how the political environment has informed his work.

Gregory Wessner: Your book Sunshine Hotel, which came out in 2019, surveyed 50 years of work. What was the experience like of putting the book together? It must have been pretty overwhelming and emotional to look back over that much time.

Mitch Epstein: Even though the book involved looking back over many years, it was very focused. All the work touches on a sense of things American—American place, the idea of what it means to be American, the psychology of America. It’s been long on my mind to do that, but I think the tension that was building in the political and cultural landscape leading up to and including the Trump era made me act on it now.

Did you know when you started out that America was going to be this idea that you were interested in exploring?

Not really, no. My first five, six years of being a photographer involved, first, being here in the city and responding to it photographically, and then moving away from that and making a series of road trips and long stays to photograph in Los Angeles and New Orleans. The work is very much about America, but I wasn’t assessing it in intellectual terms at that point. I didn’t start doing that until almost 20 years into my practice of making pictures, in the early ‘90s. In the beginning, my picture making was more free-spirited going from picture to picture.

In the ‘80s, I spent a lot of time abroad which gave me detachment and a fresh perspective on things American. It was collaborating with a dissident Vietnamese writer in the early ‘90s that forced me to confront what it meant to be an American in Vietnam. During the time I spent abroad—first in India, as my first wife was Indian, and then in Vietnam working on the project Vietnam: A Book of Changes—I realized how important my home place was to me. That led me back to America, and over the last 25 or so years I’ve made projects, beginning with The City and continuing with Family Business, American Power, and up to the present with Property Rights.

You’re putting yourself into somewhat intimate situations with people throughout America. How do you build the trust so that they let you take their picture?

With the project that I’m finishing now, Property Rights, it was a lot about how I approached my subjects. At the Standing Rock resistance action in early 2017, right before the camps were shut down by law enforcement, it was clear that the most important thing I could do would be to meet the American Indian holdouts, especially the matriarchal elders, and listen to their stories and perspective.

It’s interesting, because going into the camps at Standing Rock, I had a feeling in my stomach—a pit of fear—that was similar to the fear I felt landing in Hanoi for the first time in 1992. We were wrong to have started the Vietnam-American war, or the American War as the Vietnamese call it; and we continue to wrong American Indians as we have historically since the colonization of the United States. It was humbling as an American to face those that my country has wronged.

As a photographer, it’s essential to approach my subjects with respect, and that’s always helped with getting people to let their guard down and let me in. I want to hear what people have to say and I’m open to thinking differently. That also has a lot to do with people enlisting my trust. Listening well is crucial, and what I learn from listening informs the direction of the work that I make.

Do you work on multiple series simultaneously?

Not really, although sometimes my series have many smaller series within that I develop concurrently over time. That’s what happened with Property Rights. Standing Rock got me to explore other land rights conflicts, from Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, to our southwestern border with Mexico, and as far west as Mauna Kea on the Big Island of Hawai‘i. It’s rare that I’ll visit a site or community for the first time, and then the work is done. I’m almost always going back. I went to Lancaster a dozen times over two years. I got to know the middle-class community who formed a resistance to the eminent domain takeover of their land to build a pipeline that would carry natural gas to a port in Baltimore to be shipped to Scotland to make plastics.

When I arrived in Standing Rock it was not long before the resistance action was shut down by law enforcement. I went back a year after the closure of the camps to photograph a prayer walk commemorating the resistance action, and then furthered my work about the Lakota people and their history of broken treaties and land rights conflicts with the United States by returning to critical sites in the Dakotas, which was once Lakota tribal land.

In Lancaster, I had the opportunity to be a part of their resistance action from the beginning. I observed them as they trained for the actions with Greenpeace activists, and then when they conducted resistance actions against the pipeline over more than a year. I became close to the Clatterbuck family, who were leaders of Lancaster Against Pipelines. Mark was a professor and religious scholar and his wife, Malinda, a Mennonite pastor. They had two kids, Ashton and Hannah. Ashton was 12 or 13 years old, so I watched them grow up over three years and participate in resistance actions.

Using Lancaster as an example, you’re traveling back and forth. Over time, you’re laying the groundwork and building that trust in order to be able to take the photos and to capture the images?

Yeah, the trust was built pretty quickly.

Is that typical, to build that trust? I would think there would be suspicion, doubt, or skepticism?

Don’t I look like a nice guy? [Laughs.]

But also, I have a history, and the history is visible online and in books and publications. I think people look at my work and make their own personal assessment. And the people aren’t just subjects; we forge relationships. I get to know them, and they get to know me, but I still get to leave and come back which enables detachment. Most of my work is made with a large format 8×10 camera, and I think that also helps. It disarms people, in part because it is an archaic oddity in the era of the iPhone.

With Property Rights, I was trying to push my boundaries as a picture maker, especially during situations that were highly stressful and involved the risk of arrest. Even when I’m drawing on a kind of documentary practice, I want to make pictures that are layered and multi-dimensional, and which aspire to be more than simply a record of an event.

That’s such an interesting point when it comes to photography. So what qualities help an image transcend the journalistic or documentary and into, let’s say, fine art?

That’s so hard to define.

You know it when you see it?

Well maybe, but you don’t necessarily know it when you’re making it. Sometimes I have a sense of it because the subject is so strong that I know there is a possibility to make a compelling, resonant image. But I never really know what I’ve got on film until I see the work later, once it’s processed, and even then, it often takes me time to see the work clearly. I use my iPhone a bit to sketch with the camera: to see what three-dimensional space looks like transposed to a two-dimensional digital screen. But that’s just a starting point. The fact is that what makes a picture sing is an utter mystery, and that’s part of what I find compelling about the medium.

For works of art to be sustaining, they have to be multi-dimensional, layered. I often ask myself: How much can I successfully compress into a single picture? Is the work an authentic distillation of complex experience? And then, is the work clear, but not easily explainable?

You’ve done a couple series that are centered in or around New York City. How are you making choices about where you’re going to spend time and devote your energies?

It’s similar to the pictures themselves. Sometimes between projects, I go through periods where I’m on pause. I don’t really know what I’m going to do next. It’s listening to my intuitions, and then bonding to the ideas that come my way and seeing if they take me to the next place.

What’s been interesting over the almost 50 years that I’ve been in the city is being able to look at it freshly through my photographic practice, maybe every 10 years or so. When I came here to study at Cooper Union in ‘72, I was 20 years old. I did not know New York, and I got to know New York through photographing it.

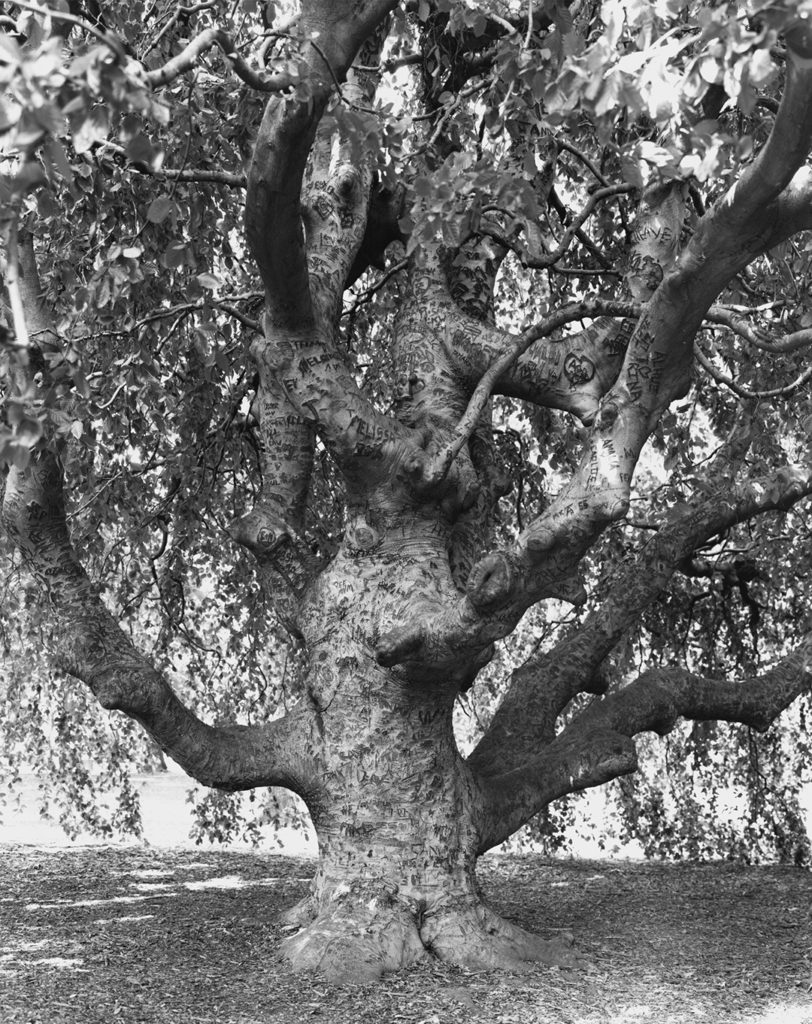

In New York Arbor, where I made a portrait of the city through photographing singular trees, I went to all five boroughs to compose a portrait of the city where nature would come forth and the city’s architecture and people recede. With my projects, usually I follow a path because I don’t have a choice but to do that. Like most artists that I know, the ideas come through the process of working itself.

Let’s talk about the research part of it, because so often the research that goes into an artist’s work, which can be expansive and quite considerable, never really gets talked about. The conversation or the attention tends to focus on the final images, the artworks, that come out of it. What does research look like for you?

I have a studio manager, Ryan Spencer. When I’m starting on a new project and even through the course of it, he spends an extensive amount of time using the internet for what it’s good for: making one thing lead to another. Because a lot of my work involves looking at a broad geography, we use Google Maps and put pins on them that have links to the research.

A lot of the work I did along the southwestern US border was embedding myself with humanitarian organizations that were working with migrants and refugees. Through the studio research, I met a Catholic sister, north of El Paso, and she took me to a number of halfway houses for refugees awaiting asylum trials. I ended up making a picture in one that was a keeper. That is an example of how the research led to making a photograph. A lot of the research, like a lot of the pictures, gets forgotten. But that doesn’t mean it’s not important to the process.

The research sometimes involves other pictures. As I photographed at Standing Rock, I looked at 19th-century photography from the west, in particular the standoffs at Wounded Knee in 1890 and then again in 1973. The visual parallels between the 19th-century photographs and the present day were disturbing. For example, the 19th-century photographs of the 7th Cavalry on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation preparing to attack the Lakota people look so much like the landscape of Standing Rock, where hilltops were fortified with law enforcement and military equipment, armored vehicles, and surveillance.

As an artist, it’s important to know what others have done historically, but also what my contemporaries are doing in the present. Over the last five, ten years, a lot of the work that has made me question my own practice was instigated by political history, but in ways that are deeply emotive and formally jarring, such as Arthur Jafa’s piece, Love Is the Message, the Message Is Death. Some of the strongest work in the late 20th-century was politically inspired and complex. Michael Schmidt, for instance, is a German photographer who is not that easily understood here. His work is very intellectual and very much about Germany. He did a project called EIN-HEIT, or U-NI-TY, that’s about the political transition before the wall came down in Berlin. October 18, 1977, Gerhard Richter’s cycle of paintings on the Baader-Meinhof Group, is another remarkable work made in response to a fraught political and cultural moment in time.

So obviously there’s been an explosion in the number of images being produced in the world now and a proliferation of devices that take images. Do you work in digital? And what’s your feeling about it?

Digital is useful. I have worked with a digital camera in the last few years, largely as a handheld camera, which enables me to make a very different kind of picture than I can with an 8×10 camera fixed on a tripod. With Property Rights, I photographed many of the resistance actions with a digital camera that enabled me to have the necessary speed and security when law enforcement threatened. I also use my phone camera, and that’s of course digital.

Digital is a mixed blessing. On one hand it allows for the democracy of photography. Almost everybody everywhere is able to make pictures with their phone cameras, and sometimes very good ones at that. That said, I’m an advocate for slow photography, for slow looking, and digital doesn’t always lend itself to that approach. I’m not a purist. I think that with photography, the tools and materials dictate the possibilities, but also the limits. It’s important to understand analog to be able to truly use digital. Otherwise, you’re relinquishing controls that you wouldn’t even know.

One question we’re asking each of the new National Academicians has to do with the National Academy itself—this group of artists and architects and the collective body of work, ideas, and energy. Do you think artists and architects have a particular role at this moment in time?

There is absolutely a role for artists because we’re not constrained by the status quo or whatever society constitutes as “normal.” Artists should break rules in order for all of us to see the world from a perspective that we might not otherwise.

For instance, I think this is a tremendous moment of possibility for rethinking historical monuments. What is a monument? What purpose can it serve in the cultural history and landscape of a nation? I went down to Richmond, Virginia, in June and witnessed the transformation taking place around the monument of Robert E. Lee. I don’t think anybody expected that it would become what it did—a place for the people to express themselves with writing graffiti all over the monument; then appropriating and renaming it as a memorial to Marcus-David Peters, a Black man from Richmond who was shot and killed by the police in 2018. It also became a larger memorial to African Americans who have been killed by police, as well as a gathering place for Black Lives Matter activists. But more than that, it became a gathering place for the community to teach, pray, dance, and celebrate; there was a tangible joy present with the takeover of what had been a painful, troubling symbol of the Confederacy that should have been buried once and for all at the end of the Civil War. Now that is transformation.

As somebody who’s been looking at America for decades now, how did you feel over the past couple of years about the direction the country has gone? Did you see it as inevitable?

The work I’ve been making is a direct response to how I feel about the state of things American. It was attending the Women’s March in Washington the day after Trump’s inauguration that led me to Standing Rock a week later. A lot has broken down. I’ve kept my faith by doing this project, Property Rights, and through the people I’ve met who put themselves on the line for what they deeply believe in; whether it’s fighting against a pipeline, helping those they’ll never meet by putting water out for migrants crossing the Sonoran Desert, or Terry Tempest Williams prepared to go to jail by buying Bureau of Land Management leases to save her beloved Utah land from fossil fuel extraction. It’s these people who’ve said, “No, this is enough. We need to protect our human rights. We need to protect our wilderness lands and be stewards of the land.” It’s these people that have encouraged me to retain some optimism. Part of the gift of doing the work I do is that it puts me out into the world, and as dismal as things sometimes look reading the New York Times in the morning, it’s still pretty beautiful out there.

I get discouraged by the flawed rhetoric and fatigue of our political process. As an American, we take a lot for granted. We have so much to be grateful for and creative potential—look at the miracle of the COVID-19 vaccine, and how well we’ve done with its distribution. I still have confidence that with the enormous challenges we face, we will make progress if we can learn to be more respectful and tolerant of one another, and less entrenched in our privileged position as Americans.

The National Academy of Design welcomed Mitch Epstein, along with Derrick Adams, Cecily Brown, Enrique Chagoya, Rafael Ferrer, Beverly Fishman, Charles Gaines, Carmen Herrera, Michael Maltzan, Toshiko Mori, Jennifer Packer, Walid Raad, Betye Saar, Beverly Semmes, and Claire Weisz as National Academicians on October 28, 2020.

Gregory Wessner is the Executive Director of the National Academy of Design. Previously, he served as Executive Director of Open House New York, and has also worked at the Architectural League of New York, the former National Academy of Design School of Fine Arts, the Parrish Art Museum, and White Columns. In recognition of his contributions to art and culture in New York City, Wessner recently received the Award of Merit from the American Institute of Architects New York. Wessner did doctoral research in art and architectural history at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York and completed undergraduate studies in Art History at Rutgers University.

A pioneer of 1970s art photography, Mitch Epstein (NA 2020) has photographed the landscape and psyche of America for half a century. His awards include the Prix Pictet, the Berlin Prize, and a Guggenheim Fellowship, and he was recently inducted into the National Academy of Design. Numerous collections hold his work, including the Museum of Modern Art and Tate Modern; in 2013, the Walker Art Center commissioned a theatrical rendition of his American Power series. Epstein has described the cultural and physical evolution of the United States from 1973 to 2019 in his Steidl books Family Business (2003), Recreation (2005), American Power (2011), New York Arbor (2013), Rocks and Clouds (2017), Sunshine Hotel (2019), and Property Rights (2021).