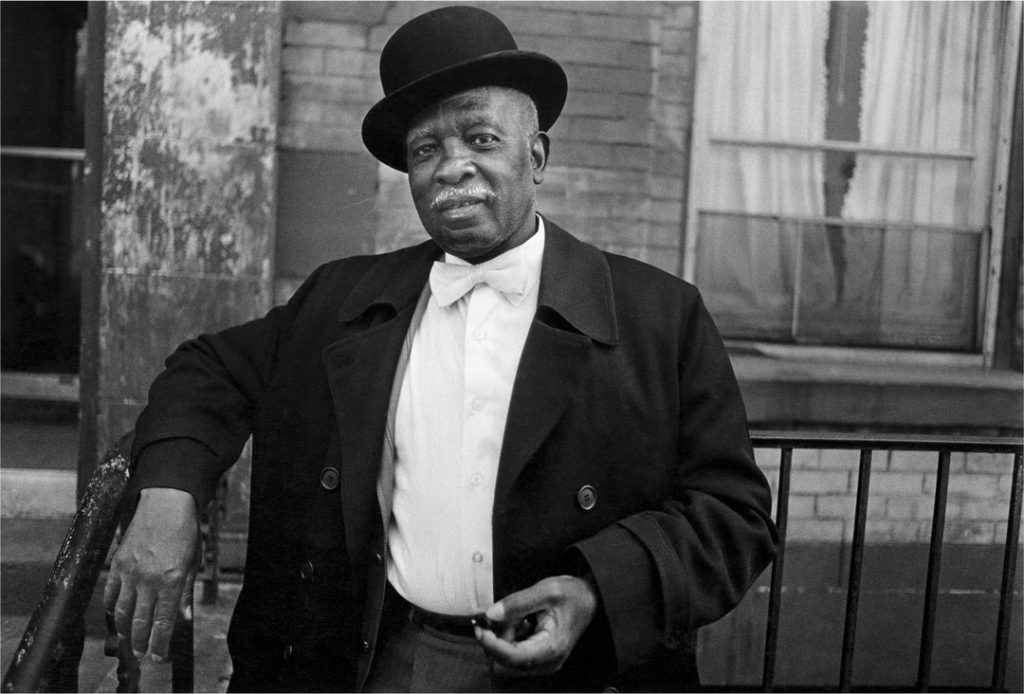

There are few living contemporary photographers whose name engenders the kind of gravitas and rigor as Dawoud Bey (NA 2015). His traveling retrospective, An American Project, is one the largest ever surveys of a living Black photographer. That this retrospective is being shown now is serendipitous. His is a career led and defined by a different kind of sight. A methodology of seeing, at once audacious, deft, and radical. Bey’s lens has been trained on the polyrhythms of Black American life in all its foundational, quotidian, and corporeal splendor.

The events of this year have shown that far too many Americans still cannot see Black people beyond the nonsensical tropes that ascribe criminality, poverty, and worse. Dawoud Bey’s work has always been positioned toward truth-telling. He has invited us to gaze upon Black people and, often, the very landscape of this country itself yoked together toward an engagement with the full density and breadth of human existence. The images he creates pierce through a veil of perpetual yet protean erasure fueled by America’s obsession with a mythic version of itself. They implore us to bear witness and to sit with the discomfort that act may cause. Through it all, Bey arms us to contend with the truth. These images are a beacon toward acknowledgement of the fullness of what needs repair here in this America. It may be among the things that can save us from the moral death looming on the horizon.

In advance of the second iteration of Dawoud Bey: An American Project that opened November 7 at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, I had the pleasure of speaking to the artist about his work and process as an artist and educator. We touched on his inspirations across fields and the power of art as a vehicle for making a statement about our time.

Niama Safia Sandy: You often say that you began making images out of a desire to affirm the lives of ordinary Black people. It is clear in the photographs you make. Beyond that, what do you hope for people to see or experience when they gaze upon your work? Has that changed over time?

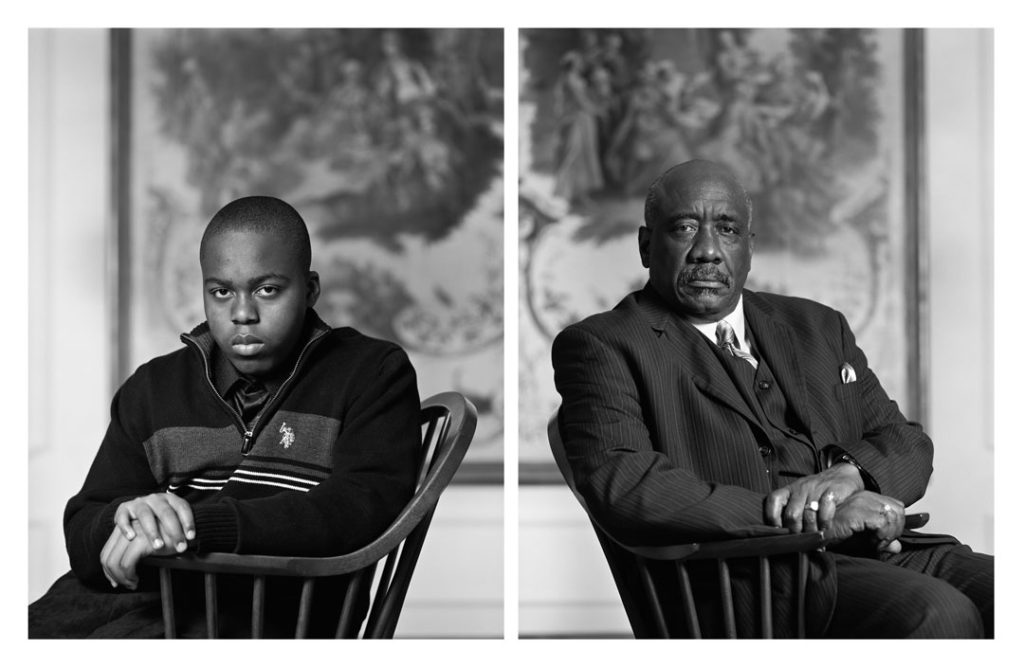

Dawoud Bey: What I was looking to locate in the portrait-based photographs that I have made over the years is a sense of interiority, a sense that the Black subjects exist not only as social beings, but as individuals with rich and complex interior lives. Black people are often described or engaged through their place in fraught social landscapes, but seldom are they afforded a representation as complex human beings. I’ve tried to create a set of circumstances in my portrait-based work that allows for that rich sense of interiority to momentarily appear on the surface.

After 50 years of making images, what brings you the most joy in the process?

One of the things that still brings me joy is being able to make the work that I make, knowing that I can marshal all of the conceptual, material, and “making” expertises that are necessary to making the work at a very high level. More than four decades in, I’m still making new work, and expanding the parameters and ambitions of my own practice.

You list Roy DeCarava, James Van Der Zee, and other pioneering Black photographers as among your influences. How have they directly impacted your work?

Roy DeCarava would be a singular influence. His use of the photographic medium was an entirely self-expressive one. Unlike Van Der Zee, he was not a studio photographer making portraits for whoever came into the studio requesting his services. And unlike Gordon Parks, he was not making work for the editors of Life magazine. His was an entirely self-directed practice. And that was what I aspired to. Seeing Van Der Zee’s photography on the wall of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in the Harlem On My Mind exhibition in 1969 marked the first time I ever saw photographs of Black people on the walls of a museum, and they were rich in their sense of self possession, aspiration, and elegant formality. He was important to me in that way. And Parks, as a Black man making his way in the world using a camera, was one of my first heroes. But, in terms of the kind of practice I wanted to shape for myself, DeCarava was my model. He was using the medium in a singular way, creating his own rich formal and material vocabulary for ordinary Black people in a way that simply had not existed before, using the visual poetics of photography. And he was consciously in conversation with the history of photography, knowing a number of the important artist photographers of his time, having conversations with them, and exhibiting their work in a gallery that he founded, A Photographer’s Gallery, the first to exhibit photography in New York as a fine art. He received a Guggenheim Fellowship—the first Black photographer to do so—in 1952, a year before I was born. It took a while, but I got one exactly 50 years later.

There is a clear sense of rhythm and timing in your images. I know you were a percussionist at one time; I would love to hear from you about music and how it figures into your approach to your photographic practice.

Interestingly enough, Roy DeCarava was also a saxophone player. And I think the expressive qualities he brought to his photographs were rooted in his knowledge and deep love of improvisational jazz music. I was a drummer. I got my first set of drums when I was 14, a year before my godmother gave me my first camera. I was fortunate to have some very good teachers when I was starting out, including Milford Graves, Albert “Tootie” Heath, and Freddie Waits. I learned from all of them the rigor and discipline required to seriously practice any art form, along with honing one’s craft, knowing the history, and understanding form and structure, and how to understand them deeply enough to be able use them freely. John Coltrane is the musician who changed my life. My first encounter with his music happened when the sax player in one of the bands I was in brought Coltrane’s album A Love Supreme to rehearsal. It changed everything for me, the sheer power of the man’s playing, and his assertion that he wanted his music to be “a force for good.” I still aspire to make work that resonates for the viewer as deeply and meaningfully as John Coltrane’s music continues to do for me. Prior to the lock down, I would go to hear live music as often as I would look at art. Jazz clubs are my thinking rooms; I go there to both relax and to be inspired. In Chicago you can find me in the Jazz Showcase, and in New York I’m a habitué of the Jazz Gallery, Jazz Standard, Smoke, and the Village Vanguard. I’ve got an upper level membership in Jazz at Lincoln Center. So, yes, the music is still very important to me. It’s a necessary part of my life as an artist.

What are the most personally resonant images you have ever made? Can you share the history of their creation and exhibition?

I think the history work I’ve been making since The Birmingham Project in 2012 is some of the most resonant. Both Birmingham and Night Coming Tenderly, Black look at pieces of significant, traumatic, and triumphant moments of African-American history and give them renewed resonance in my work. Birmingham was made in memoriam for those six young Black people who were killed on Sunday, September 15, 1963, when the 16th Street Church was dynamited. Four young girls were killed in that bombing, and two young boys were killed in acts of racist violence shortly after. Both projects seek to visualize and invoke the past in the contemporary moment; to make the past deeply felt and meaningful in our own time. Because the viewer looks at the work through the frame of history, the photographs almost inextricably pull you back into the moments that they are about. I started using black and white film again for this work, since black and white is the photographic material of history and the means by which history was captured photographically. Both projects are also realized in large scale photographs in order to create a more palpable physical experience for the viewer; to give them the space within which to immerse themselves.

I’m currently continuing this history work, photographing on and around the landscapes of the slave plantations in Louisiana. These photographs, and a video work I am making there, will be seen when the delayed Prospect.5 opens in Louisiana in fall of 2021, and then in my show at Sean Kelly Gallery.

Viewing the works from Night Coming Tenderly, Black, I have always felt a sense that the viewer is required to allow both the image and history to unfold for them. The notion that occurs to me looking at your work in general is that the site itself acts as a repository for memory and, in this body of work, Black fugitivity. I wonder about the technical choices you made in creating these images and how you connect them to those ideas.

With the Night Coming Tenderly, Black photographs, I wanted to examine the imagined landscape of fugitivity as if through the eyes of an escaped and fugitive African-American earnestly making their way through that unknown terrain, moving steadily towards Lake Erie and on to freedom. In my previous work, I have situated the subject within a particular space and place, and that place informed the narrative through which we read the subject. With the Underground Railroad work, the person is unseen but still present; we are seeing and experiencing the landscape from their vantage point. The landscape is the true subject, the memory and danger embedded in it as well as the possibility it holds for fugitivity and escape. The title comes from the true final stanza of Langston Hughes’s poem “Dream Variations,” in which he describes a “night coming tenderly/black like me.” This idea of the Black body moving through the darkness of the literal and photographic space is what brings me back to the understanding that Roy DeCarava’s richly and darkly printed photographs are a material embodiment of the conflating of Black as both subjecthood and narrative. Those large dark prints are the most technically and materially demanding that I’ve ever made.

I have rarely seen questions posed to you about your work as an educator. Has it shifted elements of your practice? What have you found most challenging? What makes you most hopeful working with students?

I’ve been teaching for almost as long as I have been making work. It’s kept me thinking through my own work even as I try to guide students in the shaping of their work. It’s been a way of remaining clear and engaged with a younger generation of artists, to see what they are thinking about and looking at, while also bringing my many years of history and thinking to the table for them. It allows me to encourage a younger generation of artists to keep their work rooted in imperative principle and purpose, to emphasize that we work because we must, and we work to leave something in history that matters.

Given the indelible impact of your career thus far, and with special consideration to the current state of affairs in this country and the world, what do you envision as the next stage of your work?

I’m always thinking ahead to the next project, even as I’m completing the current one. The next project will take me to Virginia to continue the cycle of this history work. Once that’s completed, we’ll see what’s next. The work tends to unfold out of the ideas that I’m currently working with, thinking about how else and where else I might locate my “making.” So, we’ll see…

I would love for you to complete these two sentences from your perspective. You can answer however you’d like.

Photography is… the means through which I have made my voice and concerns known for almost half a century.

Art is… vast.

What do you envision as the future of photography? What would you like to see the medium grow into and further function as?

Each generation gets to set its own agenda and definitions, so I’m not the best person to ask about “the future of photography.” Whatever it is, I hope it remains rooted in the need to engage the human community in a meaningful and transformative conversation with itself.

Dawoud Bey: An American Project is presented at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta November 7 – March 14 and the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York beginning April 17 (closing date to be announced). It first traveled to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and was presented February 15 – October 12.

Niama Safia Sandy is a New York-based curator, essayist, and musician. Sandy’s curatorial practice delves into the human story—through the critical lenses of healing, history, migration, music, race, and ritual. She is an agitator who calls into question and makes sense of the nature of modern life and to celebrate our shared humanity in the process. Her aim is to leverage history, the visual, written, and performative arts, chiefly those of the Global Black Diaspora, to tell stories we know in ways we have not yet thought to tell them, and to lift us all to a higher state of historical, ontological, and spiritual wholeness in the process.

Dawoud Bey (NA 2015) was born in Queens, New York, and began his career as a photographer in 1975 with a now iconic series of photographs, Harlem, USA. His works have since been exhibited and added to museum collections worldwide. Bey received the prestigious MacArthur Foundation ‘Genius Grant’ in 2017 and is also the recipient of fellowships from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts. He holds a Master of Fine Arts degree from Yale University and is currently Professor of Art and a Distinguished College Artist at Columbia College Chicago, where he has taught since 1998.