Last month, the National Academy of Design welcomed its newest class of National Academicians, 15 extraordinary artists and architects who join a community dating back to the founding of the NAD in 1825. Learn about the election process and watch the induction ceremony here.

As part of this year’s celebrations, the NAD’s newly appointed executive director Gregory Wessner interviewed each of the incoming members to talk about their work and ideas, and how the upheavals of the past year have affected their practices. Conversations will be released throughout the coming months.

Claire Weisz (NA 2020) is a founding principal of New York-based WXY architecture + urban design. WXY works closely with local communities to create and reimagine public spaces and structures such as Astor Place, the Rockaway Boardwalks, the SeaGlass Carousel in Battery Park, and the Sanitation Garage and Salt Shed—which Michael Kimmelman of the New York Times called “New York’s Best New Public Sculpture” in 2015.1

In this conversation, she discusses how she involves members of the public in the design process, how drawing can strengthen communication, and the role activism plays in architecture.

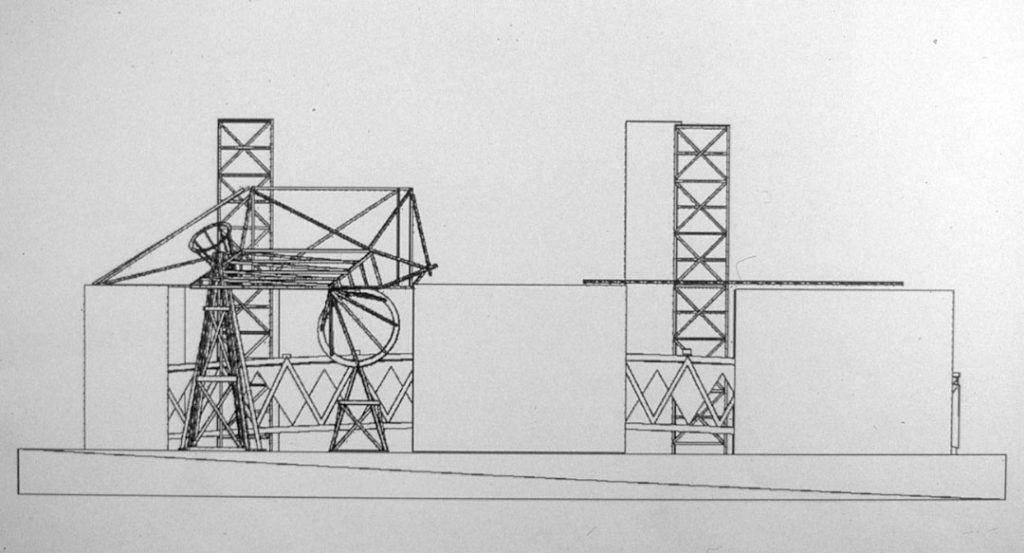

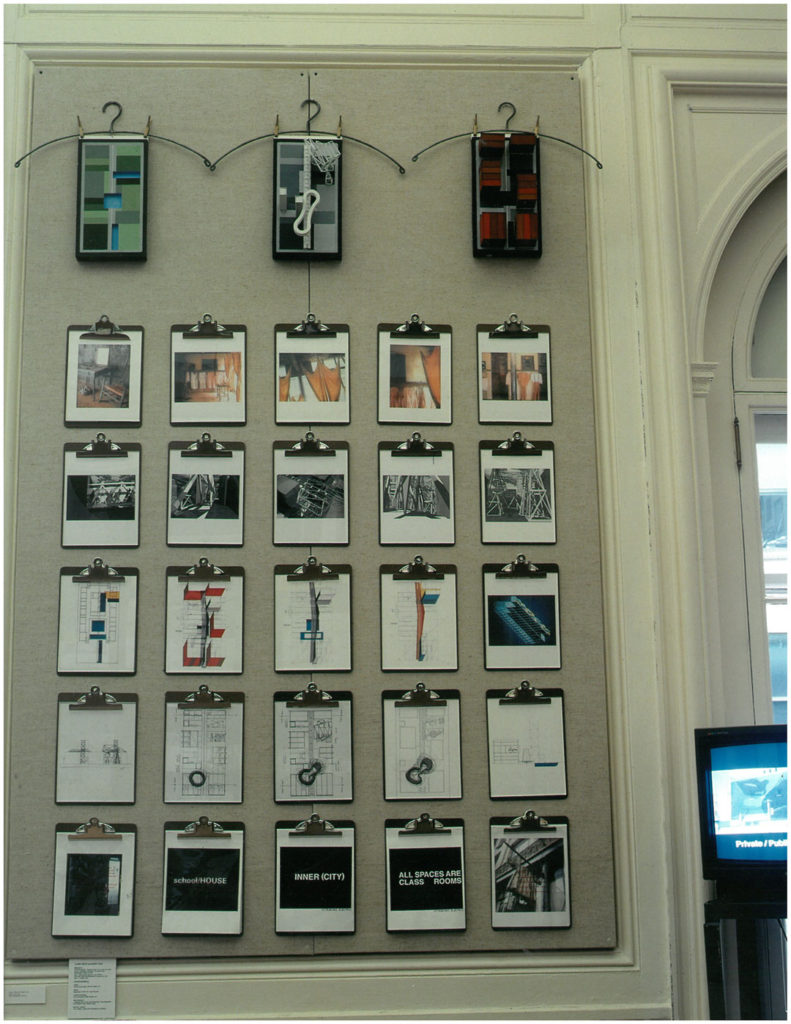

Gregory Wessner: You and your partner, Mark Yoes, won the Architectural League Prize in 1993, which was the first League Prize exhibition that I helped out on. What do you remember of that show or winning?

Claire Weisz: At the time, Mark was working for Pei Partnership and I was mostly teaching, but it was an era like we have now. It was the “stay alive till ’95” era. To win the League Prize, I put together three books called Beg, Borrow, Steal. Mark and I collaborated on the key project, which was the beginnings of computer video, but it was created by designing an apartment with a video artist. Ulla Warchol, my first architecture partner, and I made books out of salvaged materials and industrial felt; books basically about practice as a barter system. I look back to this today and I think that is so neat.

There was a period where your studio was small—and then seemingly overnight, it had just exploded. I remember walking into the office at some point and it had just taken over the whole floor.

For a long time, the practice was focused on finding a way to link projects to things we thought needed to be cared about more, like the environment or community. Then it all started to find a way to stream together as one practice.

You have threads of starting an organization like the Design Trust for Public Space with Andrea Woodner—that was part of the practice. Teaching at City College was also part of it. With Ulla, I had our Weisz and Warchol practice, where we built all of our projects. The last project we did together was Spoonbill & Sugartown, the bookstore in Williamsburg, Brooklyn.

David Burney, who at the time was Director of Design and Capital Improvement for the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA), gave us our first real work, designing three NYCHA community centers. Mark worked on the Museum of Jewish Heritage Visitor Center in the evenings. At some point before this, Ulla had left and decided that she was going to be her own client and primarily make books.

WXY got bigger because we were doing public work during the beginnings of the Department of Design and Construction’s Design Excellence program. I really do credit that program with making it possible for us to grow.

DDC’s Design Excellence program specifically was critical?

It was key because it grew out of the work we were doing. It enabled a solid mix of opportunities that were challenging but allowed us to figure out how to deliver on this focus of public space in built projects that have insides and outsides. Through that process I started to see how opportunities unfold. It started with Beg, Borrow, Steal—the idea of not being defined by your commissions, and instead being defined by the opportunities you made.

Being asked to submit for the League’s Emerging Voices award was the moment when it became clear to us that it was possible to make a new kind of practice, one that wasn’t a not-for-profit. A proactive practice that may not be traditionally subject-oriented, meaning by specializing in certain building typologies. It was public space writ large, I’ll call it.

In general, the firm proves itself by practicing in a way that allows spaces and places to be themselves and engages people in being the clients for that process. You have to keep drawing and making to understand what you’re doing, but architecture doesn’t happen without a collaboration or a client. It doesn’t happen with any single person working alone. But how do you make that moment happen for more people in the right way?

You, as much as anyone else I can think of, have really made community a genuine partner in your process.

People see community as a group of 25 people showing up at a meeting. I think part of the reinvention is to not see it that way, and instead see many different techniques for engaging a community. Going for a walk with three people who live nearby, showing up at a meeting and being willing to draw with whoever else is there, working really carefully on a survey that could go to tens of thousands of people to make sure there are questions that you think will intrigue people. Or knowing that someone who is 10 or 12 years old might be engaged by something less obvious, whether it’s the colors in a space or the way a building is shaped. I think the Sanitation Garage and Salt Shed worked that way. The SeaGlass Carousel works that way. Knowing that someone who will be affected may not be at the table, how do you make that knowledge part of the process? That’s really the issue. How do you take a group of people who are privileged enough to be at the table—including the client who is paying for it—and help them be in a position where they’re taking responsibility for others who are not yet at the table?

How do you get the clients who are controlling resources to become advocates?

I’m going to admit some truth here. I think most people won’t say yes to some of the best ideas because there’s an inherent conservatism. When everyone sits together and decides what they agree on, it’s not necessarily the thing that’s going to be able to work or the right ideas. You have to know at what moment there’s an entry point for making a connection and expanding the vision. In most cases, that happens by slowing down processes so that you can listen and wait for the right moments. Or if something’s going fast, like in some of our early projects like the Museum of Jewish Heritage’s visitor pavilion, you have to seize the moment in the constraints. As an architect, you have to do what you can to hold on to something with the hopes that it will point the way to the future.

How have the pandemic and protests affected your work and practice?

I’m drawing a lot more by hand.

I was thinking about this question of drawing in preparation for our conversation. I don’t think we’ve ever talked about the importance of drawing to your work.

Well, in a lot of ways, the computer and the process have overwhelmed the importance of drawing. For many architects, that role is not as important anymore. I’m lucky enough to have a partner in Mark who draws unbelievably well. And so the pressure on me to draw is usually in the moment with people. And now with COVID-19, I’m not sitting with people in the same way I used to. I’m working on a project for an artist residency, for example, and I recently met with the client outdoors and drew. Out of that came more drawings, more thinking. It reminded me that striking a line across the page with someone in order to talk to them is so valuable. I do it on Zoom, too, but it’s not quite the same.

How often are you drawing? What is your drawing practice like?

It’s in the realm of solving problems and thinking through stuff. I’m not getting on the subway and running around right now, so there’s more time to dedicate to drawing. There’s time to do three or four drawings a day, which wasn’t possible before. That never happened before March.

Let’s go back to the idea of drawing in community meetings, and drawing becoming a shared form of communication that pulls people together. What is that like?

To me, this is the fundamental way that you collect information in an authentic, straightforward way. People may say something, or move their hands, or do something, and if you draw it, they can respond and say, “No, I was thinking…” You can move that forward. It’s fundamental to have people exchange ideas. Ultimately, community engagement is about a true exchange of ideas, not about everyone voting to agree that something has to be a particular color. Drawing with someone is still the core to how it happens.

In light of what’s been going on the past six months, how are you feeling about the world?

I’m energized by the realizations, consciousness, and awakening that the Black Lives Matter movement has made happen. All the marches and protests that I’ve gone to have made me connect to being with people in spaces. I’ve stayed in New York City, so it’s through that lens. Other than going up to Storm King Art Center once and out to Newark a bunch of times, it’s been super local for me. In the past, I’ve always felt that the practice was generally local, but it was complimented by being able to travel, see how other things are done, and meet with people in other places. Now, without travel, there’s a focus on looking at where we are and seeing New York transformed through open streets and eating outdoors, and it’s always surprising. Since the practice tends to focus on interpreting the data of the city, there’s so much going on.

It was really meaningful for me to be part of helping the Black Lives Matter mural happen on Centre Street—to see Kendal Henry, the Director of the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs Percent for Art Program, curate three younger artists, Sophia Dawson, Tijay Mohammed, and Patrice Payne, for their first public art commission. Those are the hopeful things. Also, remembering that each project is an opportunity to get people to look at their neighborhoods, buildings, and neighbors differently, and to try to effect change that way.

You have committed so much of your work and energy to supporting civic life in this broad sense.

I’ve only been able to do that through collaborations and conversations with people I’ve met—artists and architects like Xenobia Bailey, James Stewart Polshek (ANA 1983; NA 1994), and Mierle Laderman Ukeles; government partners like Maria Torres-Springer when she was President of the New York City Economic Development Corporation; and non-profit leaders like Nancy Biberman who founded WHEDco. Even, you, when you were at Open House New York.

These are people who build things—and they’ve been building them for years. I’d call it social impact or civic-ness. These people aren’t stopping now because of COVID-19. No one is giving up. There’s a huge amount of hopefulness. We’re still the same people, and we’re still trying to make sense of everything. But I do think it’s becoming harder and harder for local leaders and makers to exist. It’s like everyone has been on a starvation diet of leadership. You can survive like this, but to thrive requires supportive institutions and framework.

To me, your practice has always been an activist practice. Is that how you see it?

I have always seen that I couldn’t be a bystander. My view comes from the feeling that if you are an architect, privileged enough to be in a position where you are allowed to take on the blank page, you therefore cannot be a bystander. By nature of being an architect, you must consider what you do as an activist, which means that you’re an active agent of change. When you become passive to that idea, it’s problematic because you’re not looking at the effects of your work. Architecture can be very disruptive, so you have to document both the pluses and the minuses.

The National Academy of Design, at its heart, is a collective of 450 artists and architects and all that they represent in terms of work, ideas, energy, and passion. What role do you think an institution like the NAD plays now? When I say, “institution,” I mean the National Academicians themselves. What role should all of you be playing as we look forward? We need ideas for where we will go next and what kind of world we want to live in.

Institutions are individuals anyways. Whether they are affordable housing not-for-profits or the Borough President’s office, it always come down to individuals. The National Academy of Design is ahead of the game by admitting that this is a group of individuals, so the question is: How can an organization help individuals connect to more individuals? Maybe some need to connect to others who are part of the National Academy of Design, but maybe not. With Zoom, it’s now much easier to connect to people, but what’s not easy is to understand what someone knows that they’re willing to talk to you about, what someone knows because of the work they’ve done, and how we can connect to each other and make the impacts we have wanted to make.

Have you thought about the role of artists in this moment, and what they can be doing?

I’ve noticed that people are looking harder at things, like with music. When I see people in New York practicing outside, there is joy that is, in a lot of ways, just life lived. You see people living, and art and music are part of their daily existence. With COVID-19, you realize how hard it is to make those things happen. I’ve been reflecting a lot on how it’s those moments of living that an artist has been working on their whole lifetime.

I respond to art in a way that is essential in times like this because a lot of our other systems are rigid. Architecture tends to be linked to rigid systems—how things are financed and built—whereas artists are tied to being able to understand what can change in people’s rigid outlooks, their preconceptions, and even how you might build something.

No one would have ever wished for any of this to have happened, but it has made us recognize things that we may have taken for granted, like going outside, enjoying parks, having access to public space, visiting museums and experiencing art. This stuff isn’t a luxury. It’s essential to our humanity. What do we all take away from this time and bring forward into the way we rethink how the city works—how the world works?

Arts education is so important for everyone. In a time like this, it’s clear with younger people who have been exposed to thinking and training as an artist or architect. When given such blank slates, like these “What do we do now?” moments, they’re open-minded, but also analytical. How do you look at a space, a place, a color, a composition, a dilemma? It’s not training based on memorizing facts or being told which formulas work. We should be listening to younger people more because they’re closer to unfettered ways of thinking. And, more importantly, if we don’t get a huge amount of arts education for everyone back in our schools, we’re committing a deep error. The only way to counter disinformation is curiosity.

The closer we can bring arts and sciences together—to teach science through art, and to teach art through science—the more we can fund the fields and give people stable jobs through them. That’s the hopeful part, if we can pull that off. There’s been a huge attack on arts education for decades, and especially recently. Those who have been privileged to have these educations—whether they’re writers, visual artists, or architects—have more coping skills than many people.

The National Academy of Design welcomed Claire Weisz, along with Derrick Adams, Cecily Brown, Enrique Chagoya, Mitch Epstein, Rafael Ferrer, Beverly Fishman, Charles Gaines, Carmen Herrera, Michael Maltzan, Toshiko Mori, Jennifer Packer, Walid Raad, Betye Saar, and Beverly Semmes as National Academicians on October 28, 2020.

Gregory Wessner is the Executive Director of the National Academy of Design. Previously, he served as Executive Director of Open House New York, and has also worked at the Architectural League of New York, the former National Academy of Design School of Fine Arts, the Parrish Art Museum, and White Columns. In recognition of his contributions to art and culture in New York City, Wessner recently received the Award of Merit from the American Institute of Architects New York. Wessner did doctoral research in art and architectural history at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York and completed undergraduate studies in Art History at Rutgers University.

Claire Weisz (NA 2020), FAIA, is a founding partner with Mark Yoes, FAIA, of WXY architecture + urban design, whose work as an architect and urbanist focuses on innovative approaches to public space, structures, and cities. Weisz was awarded the Medal of Honor from AIANY in 2018 and was honored with the Women in Architecture Award by Architectural Record in 2019. WXY is globally recognized for its place-based approach to architecture, urban design, and planning, and has played a vital role in design thinking around resiliency. In 2019, Fast Company named WXY one of the World’s Most Innovative Architecture Firms.