Last month, the National Academy of Design welcomed its newest class of National Academicians, 15 extraordinary artists and architects who join a community dating back to the founding of the NAD in 1825. Learn about the election process and watch the induction ceremony here.

As part of this year’s celebrations, the NAD’s newly appointed executive director Gregory Wessner interviewed each of the incoming members to talk about their work and ideas, and how the upheavals of the past year have affected their practices. Conversations will be released throughout the coming months.

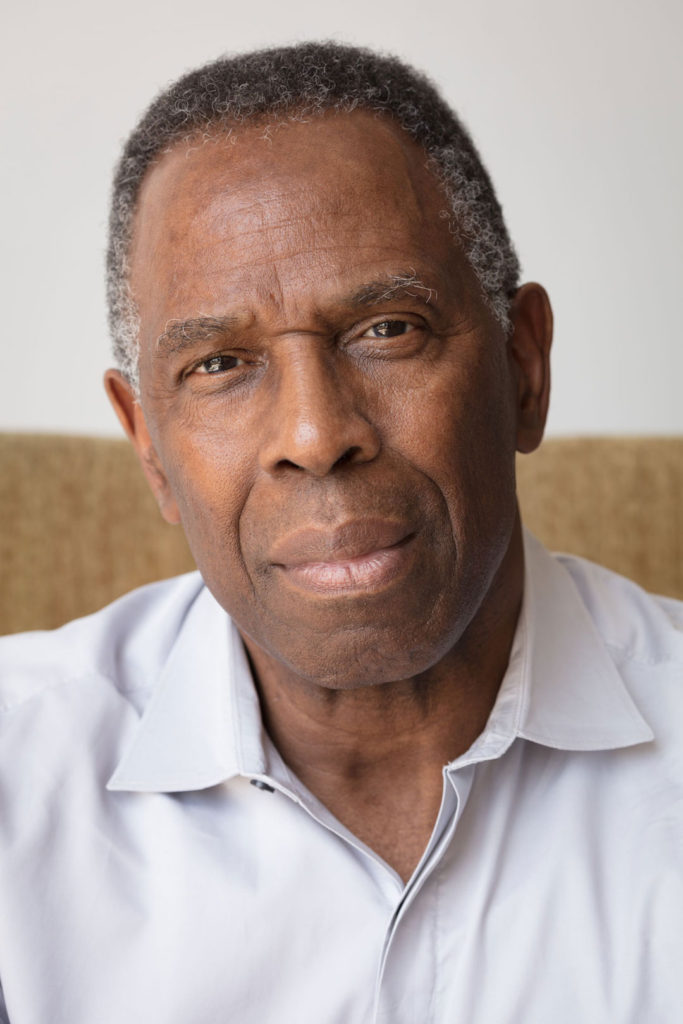

We are thrilled to launch the series with this interview with Charles Gaines (NA 2020). Gaines is a Conceptual artist based in Los Angeles, where he is a member of the California Institute of Arts faculty. Gaines was born in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1944, and grew up in Newark, New Jersey. In this conversation, Gaines speaks about his graduate school realization that he was uninterested in self-expression through art; the artists and books that led him to develop algorithmic, systems-based work; and the ideologies behind the systems we encounter in our daily lives.

Let’s talk a little about the systems that you use to make your work. Going back to the beginning, how did you arrive at that idea of creating systems that would in turn generate the work?

It really goes back to graduate school. What directed my practice was coming to terms with my own sensibility, because that sensibility did not reflect the general notion about how artists should think and act and behave. I had no affection for the process of making art.

Before I went to graduate school, I was making these René Magritte-style Surrealist paintings. I didn’t want to continue doing that because it was derivative. The process was simply imagining something, intuiting a mark, and working from that. I would see my colleagues producing work from their imaginations, being satisfied, and feeling connected. I could follow that process and make work, but I didn’t feel connected to what I was making.

I was curious as to why that was happening, and I began to get a clue after coming into contact with two books: The Life of Forms in Art by Henri Focillon and The Tantric Way by Ajit Mookerjee. What I discovered in both is this idea of the autonomy of materials, the autonomy of matter, and that the way materials form or behave is its own sort of will and volition. These sources taught me that you’re being molded by material as much as you are molding the material. I started to say, “Well, there must be a way I can take this idea on and make artwork.”

When I was thinking that, I saw the work of Hanne Darboven in New York. She was showing at Sonnabend Gallery, Castelli Gallery, and the Museum of Modern Art at the same time. Darboven’s work is extraordinarily repetitious. It’s not systematic, but it deals with this kind of redundancy and repetition, which I thought was interesting. It was the first time I saw something that was totally not informed by the expressions of imagination. When I first saw her work, I got really mad. I said, “The drawing I saw at Castelli looks exactly like the drawing I see at MoMA. What’s going on here?” I spent the whole day looking at the same thing. I couldn’t understand it, but I kept going back.

But it really just comes down to how you define or perceive difference. In this case, what are seemingly inconsequential shifts lead you to totally different places, right?

Exactly, which I totally missed at the beginning. I must’ve seen those exhibitions three times. Suddenly it dawned on me that what was important about that work was that it wasn’t coming from her own ego. I liked that, and I liked that it was a conceptual approach to making art. A lot of people think that my first influence was Sol LeWitt, but he wasn’t. LeWitt was an extraordinarily important factor in my work for other reasons, but the first Conceptual work that made sense to me was Darboven’s.

I stopped painting and started doing drawings. I went through a year of pretty awful stuff. Then, I got the idea that rather than copying Darboven’s repetition, there might be another avenue to dealing with this idea of systems, and dealing with this idea of avoiding the expressive ego. That’s where the Mookerjee book came in handy, because I started these drawings of the Tantric months that are visions of the structure of the universe, and it occurred to me how this came from a rigorous practice. It wasn’t expression. I thought, “I’m not a Zen monk, and I can’t pretend to be one, but there must be a way within Western language that would allow me to do the same thing.” That’s where I started thinking about systems and mathematics.

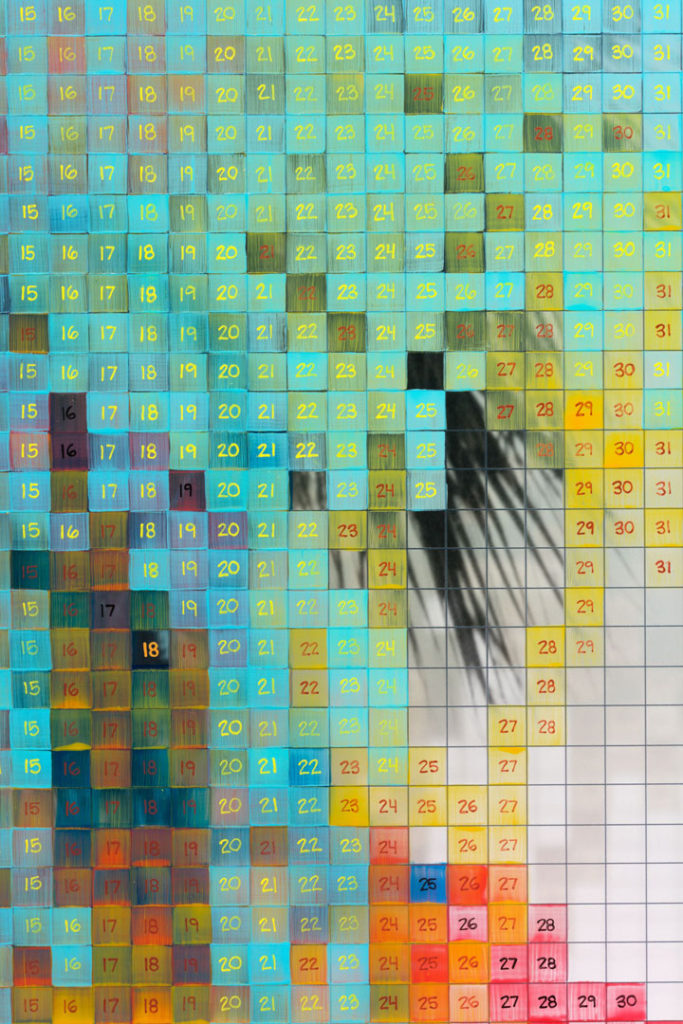

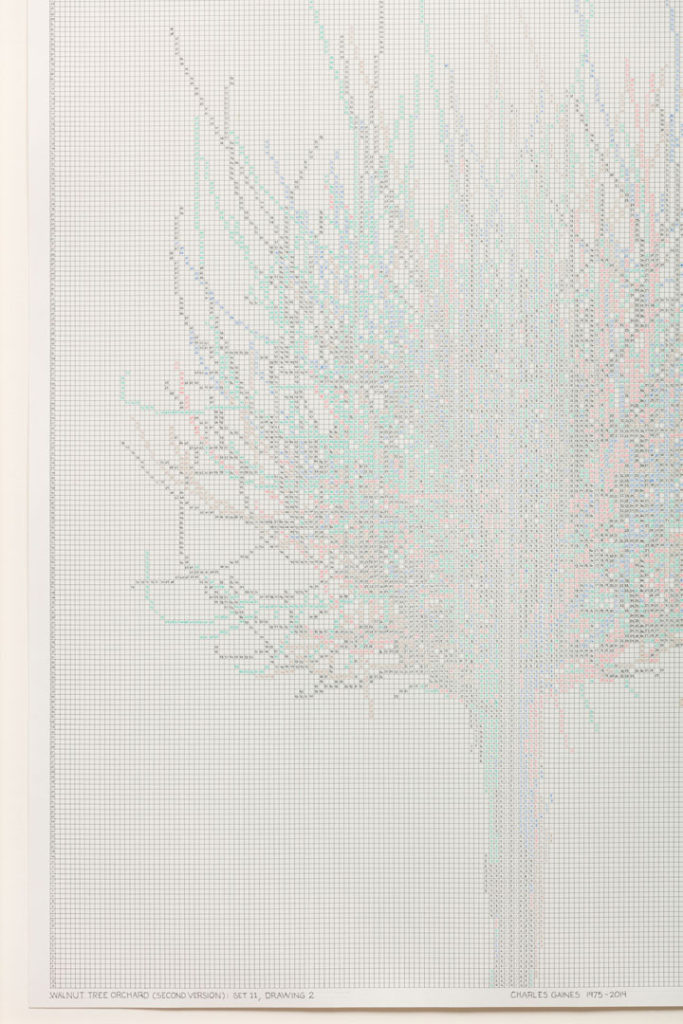

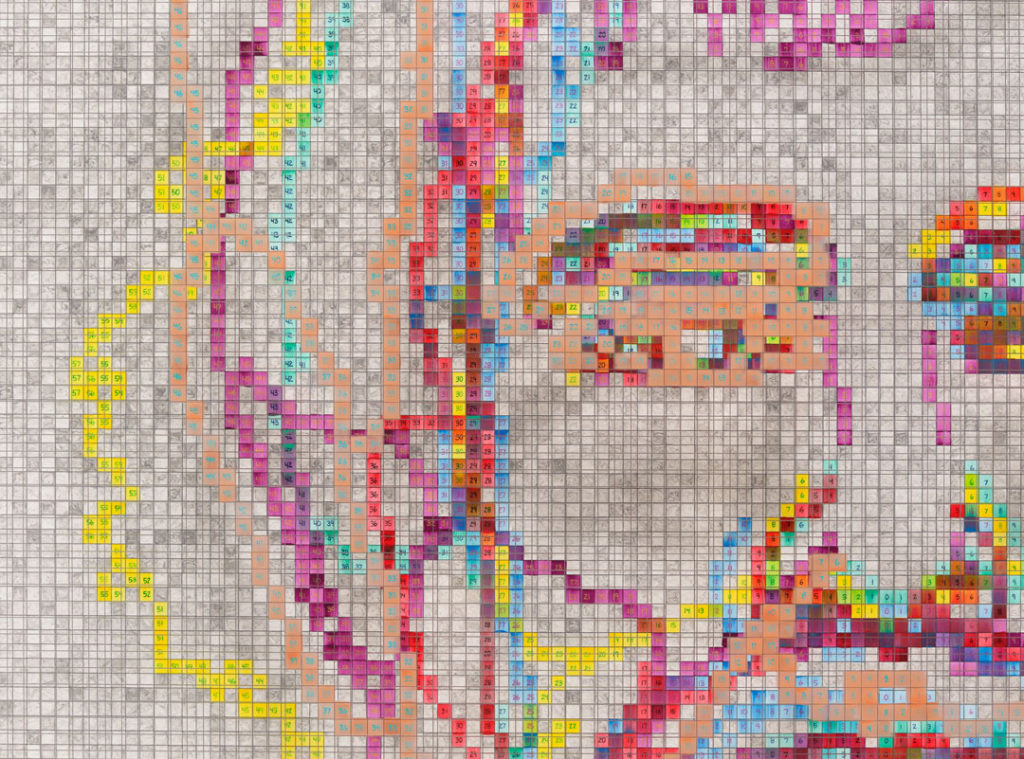

My earliest drawings were the Regression series, where I used an x/y-based formula. I divided the page by a grid, so I could have numbers in order to calculate. The calculation was simply x times y. I would plot out the numbers and create these hyperbolic shapes on the paper. That interested me because the form was not produced by my imagination. It was produced by a system. I was a spectator to my own making, so I didn’t know what would happen. It was always a surprise. That was a really nice relationship to have with work because then I knew that my ego could be fed in this process simply by being delighted by what I saw, and without creating an illusion that the result was a pure invention of my ego.

You brought up the Mookerjee book earlier. Buddhism is so much about coming to terms with the ego and confronting the role of the ego in the world. For you and your work, how much of it is about removing ego from the system so that you go on a journey that you follow, as opposed to your ego leading it?

That’s right. Early on, when I claimed that I was making work not driven by my creative imagination or expressive ego, a lot of people pointed to things that they thought belied what I was claiming. I have had to polish this idea of how I think I’m making art. For example, people would say, “You created this system.” And I would answer, “The creation of a system does not demonstrate the fact that I’m making art, because scientists go through the same process of imagining, and they’re not making art.” You can call science art, but it’s an entirely different use of our intuitional faculties.

Also, I want to make clear that the work that I did was directly a consequence of my lived experience and culturally conscious. My interest in working with systems and processes was because I had existential questions that came out of my experience living in the Jim Crow South; questions like: Who authorized this system? Why is this person better than that person? Why can’t I drink water out of that fountain? I was interested in interrogating culture. My interest in systems was the process of interrogating strategies, the received strategies of what art is, and what constitutes an art practice.

From early interviews with you that I’ve read, my sense is that audiences didn’t know how to understand the work you were making. It certainly didn’t seem like they were understanding that it had a direct connection to the lived experience of growing up in the South, becoming an artist in the mid-1970s at a moment of intense political activism, and how you fit into an overarching story about art-making.

You’re absolutely right. It was a difficult case to make. Interestingly, it was a while before I understood it. I have to thank the interest in critical thinking about race in the ’70s that forced me to start thinking about what we’ve been talking about, because when I started making the systems work, my white artist friends thought it was continuing the strategies of Conceptual art. I call myself a Conceptual artist, so I don’t have a problem with that. But the problem I have is with the idea of Conceptualism being universalist; the approach of the idea being a manifestation of its universal import. I have a problem with that because I really want to reinforce the idea of culture. My Black friends, particularly the ones who were invested in the Black Power movement, thought I was making white art. They were asking me, “Why are you making white art?” And I said, “I’m not making white art.” They said, “Well, it looks like white art.”

That led me into a process of research and reading and getting deeply into philosophy and critical thinking that allowed me to find a language to make an argument for why this work has social and cultural relevance. It has been a process because it’s still hard for people to see beyond the formalism of Conceptualism.

The topic of research is a good segue. You have a show coming up at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) early next year, right? The fourth piece of your Manifestos series.

That’s right. It’s in the works.

When you approach a new project like that, what kind of research are you doing? And how do you use that research? How does it feed into the work?

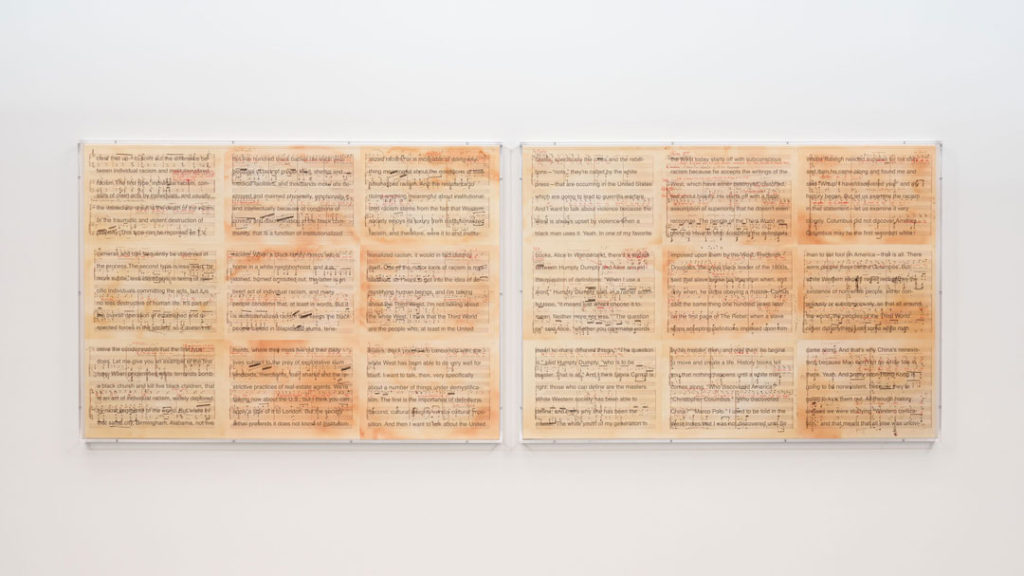

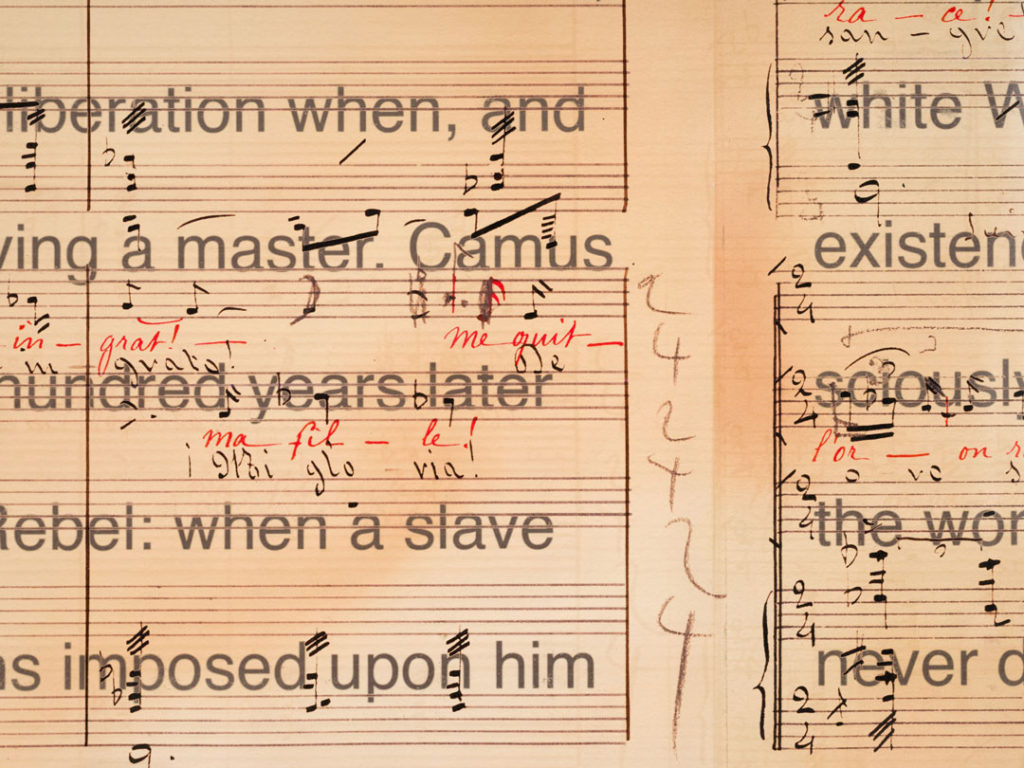

I use reading in the broadest sense as a way of discovering the ideas of others. What I’m looking for when I read is to have my own views changed, or to find a situation that destabilizes any position I might have. To that extent, research is core to the work. Manifestos came out of a body of work that I call the language-based work, where I make art that’s driven by content, but have the linguistic structure of that material inform the objects or the images that I make, rather than my subjectivity.

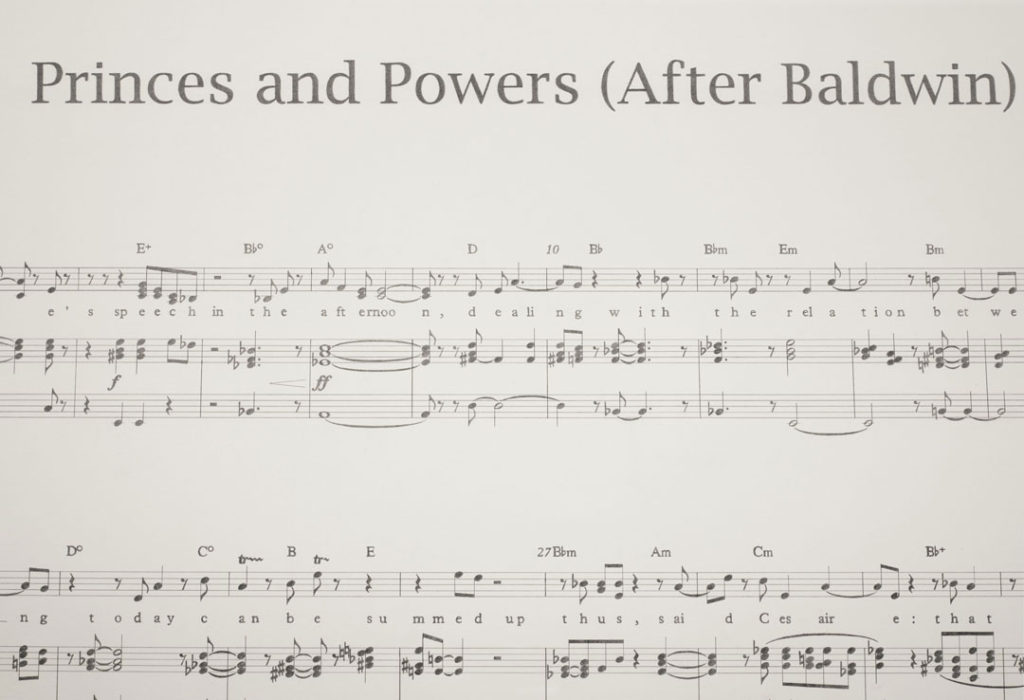

In this case, I should mention that I was trained as a percussionist, and I played jazz professionally for a few years, so I know music theory. I was always curious why my interest in music and visual art couldn’t collapse, but I decided that it was always going to be that way—my music was not going to enter my art practice—until I met Terry Adkins, who had no problem intermingling his music and art practices. It wasn’t because of Terry, but at about the same time I met him, I decided to use a political text and develop a system whereby the letters could be converted to musical notation. It brought together two things that are unrelated—the practice of forming musical compositions and the practice of writing political texts—and made a system where they can interact, or one can help produce the other.

In the show at SFMOMA, the text I’m using comes from research that I did at the St. Louis, Missouri, courthouse on the trials of Dred and Harriet Scott. I took the trial transcripts and computed them to musical notation. The compositions are constrained by the system of translation, but not exclusively, because after the translation I make changes that respond to my tastes.

The music is recorded, and in the installation, the political text is scrolled on video monitors, and the music derived from them is played simultaneously. When people look at this, they feel there is an inescapable connection between the music and the content of the text. I try to explain that what you feel are legitimately interpretations of the experience and not something that I was trying to shape or carve out.

That raises an interesting point about your work in terms of its relationship to beauty and emotion. That’s not really the point for you, is it? Meaning, for people to experience beauty or to have some kind of emotional experience with the art.

No, but I use beauty as a subject area because we attach it to this critique of art. What I want people to think about is that what they’re feeling is not the triumph of their own ego or subjectivity. What they’re feeling is a consequence of what they’ve been acculturated to feel. A lot of people think that individual consciousness is this privileged space that should not be violated. When you claim that what you’re feeling is a consequence of what you’ve learned, you’ve undermined this idea of the autonomous, unfettered connection to your subjectivity.

People get mad about that because they want asubjectivity to be this truly transcendent space that goes beyond culture and politics and reinforces why each of us is different from somebody else. If I’m making this claim that you’re part of a community, and the experiences you’re having are a consequence of your lived experience in that community, for some reason, they think that’s a problem. I don’t think it’s a problem at all. I think it makes you hyperaware of the influences on your life. I feel that art has been one of the worst perpetrators of this kind of myth. That’s why I take this on as a critical subject.

When your work deals so much with thinking about underlying systems or creating systems, are you looking around all the time, trying to understand what the systems are that underlie what surrounds us each day?

Yeah. I’m trying to unpack the ideological presuppositions and determine: Who’s benefiting from this kind of thinking? One recent example: I saw in The New York Times that four museums have canceled the Philip Guston (ANA 1980) retrospective because of his Ku Klux Klan paintings, hood paintings. I could not believe that these sophisticated museums would do such a thing. Essentially, the museums are saying that they want to represent a more balanced picture. These are supposed to be sophisticated thinkers. They should understand nuance and poetics and metaphor and be able to negotiate those ideas through this moment where there’s a heightened sense of the responsibility to understand differences and the history of racism.

The overriding principle here is white privilege. The museums are creating this mythic space to protect themselves from controversy. But, in creating that space, they created this fiction of a group of Black people who are going to get mad. Before, they didn’t care how Black people would think, and now, in order to care about what Black people think, they have to create Black people in order to demonstrate their thinking. I just found that completely… I’m still shocked by it. They have taken my interest in critically interrogating the history of race in the United States and turned it into a dogma in which they can make this kind of unthoughtful decision by simply constructing this crazy binary. It’s personally offensive. And they have the privilege to do that.

Is it hopeless to expect that we’ll ever be able to have a nuanced conversation again? Or is it always going to be reduced to some binary conflict, without allowing for complexity and discomfort?

That’s what’s at stake, whether those museums can actually understand how they created a fictional space to protect themselves from controversy. I don’t know. I hope so.

The National Academy of Design welcomed Charles Gaines, along with Derrick Adams, Cecily Brown, Enrique Chagoya, Mitch Epstein, Rafael Ferrer, Beverly Fishman, Carmen Herrera, Michael Maltzan, Toshiko Mori, Jennifer Packer, Walid Raad, Betye Saar, Beverly Semmes, and Claire Weisz as National Academicians on October 28, 2020.

Gregory Wessner is the Executive Director of the National Academy of Design. Previously, he served as Executive Director of Open House New York, and has also worked at the Architectural League of New York, the former National Academy of Design School of Fine Arts, the Parrish Art Museum, and White Columns. In recognition of his contributions to art and culture in New York City, Wessner recently received the Award of Merit from the American Institute of Architects New York. Wessner did doctoral research in art and architectural history at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York and completed undergraduate studies in Art History at Rutgers University.

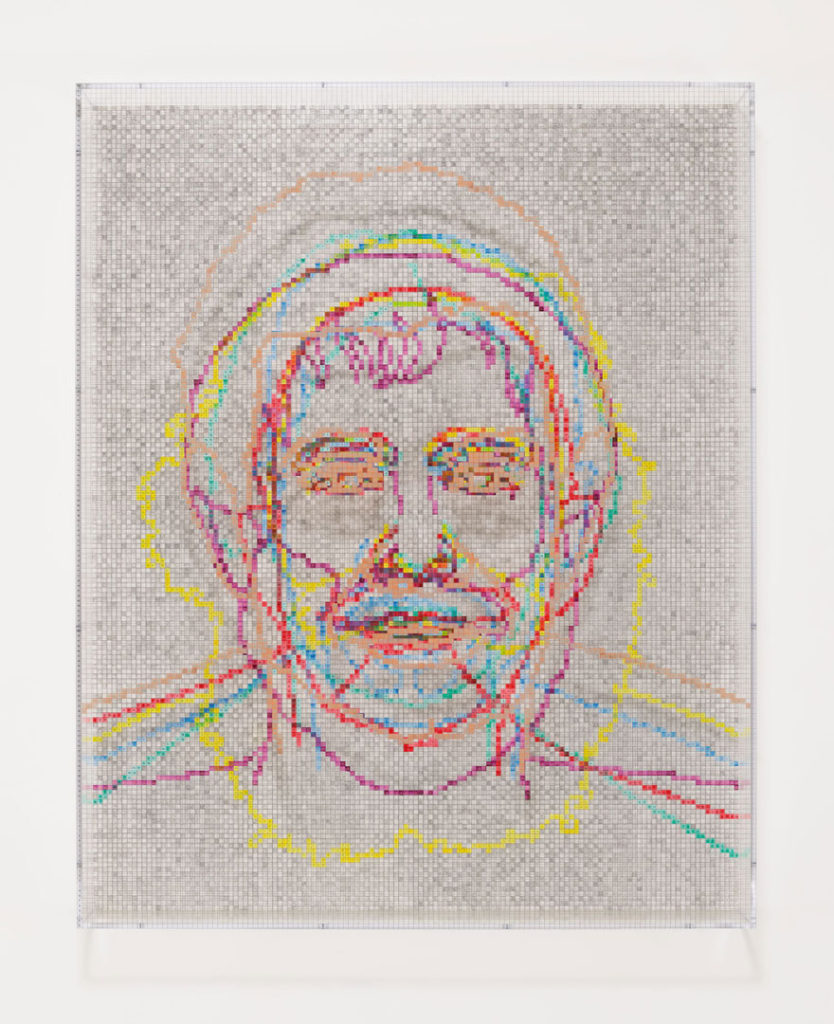

The work of Charles Gaines (NA 2020) engages formulas and systems that interrogate relationships between the objective and the subjective realms. Using a generative approach, he has built a bridge between the early Conceptual artists of the 1960s and 1970s and subsequent generations who are pushing the limits of Conceptualism today. His work is in public collections including the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Studio Museum in Harlem, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Whitney Museum of American Art. Gaines lives and works in Los Angeles, where he is a member of the CalArts School of Art faculty.