The “From the Collection” section of NAD NOW provides an excellent opportunity to share stories about the National Academy’s unique history and important permanent collection; whether it be the discovery of a hidden treasure, the conservation and restoration of one of our works, the addition of a new gem to the collection, or an interesting anecdote about our history and membership that shouldn’t go unshared.

A brief explanation of how our collection has formed is in order. Since its founding in 1825, the National Academy of Design has upheld a longstanding rule: any elected Academician must offer to the collection a representative example of their work, known as her or his Diploma Work. In 1839, it was decided that any artist nominated to the preceding rank of Associate would also gift a self-portrait, or portrait of themselves executed by a colleague, known as the artist’s Diploma Portrait. Although this additional requirement was eliminated in 1994 when the Associate level of membership was phased out, these artist submissions have accumulated over nearly 200 years to form a collection unlike any other—one built by artists, and one that tells, through their eyes, the story of the Academy’s role in the cultural landscape of this country.

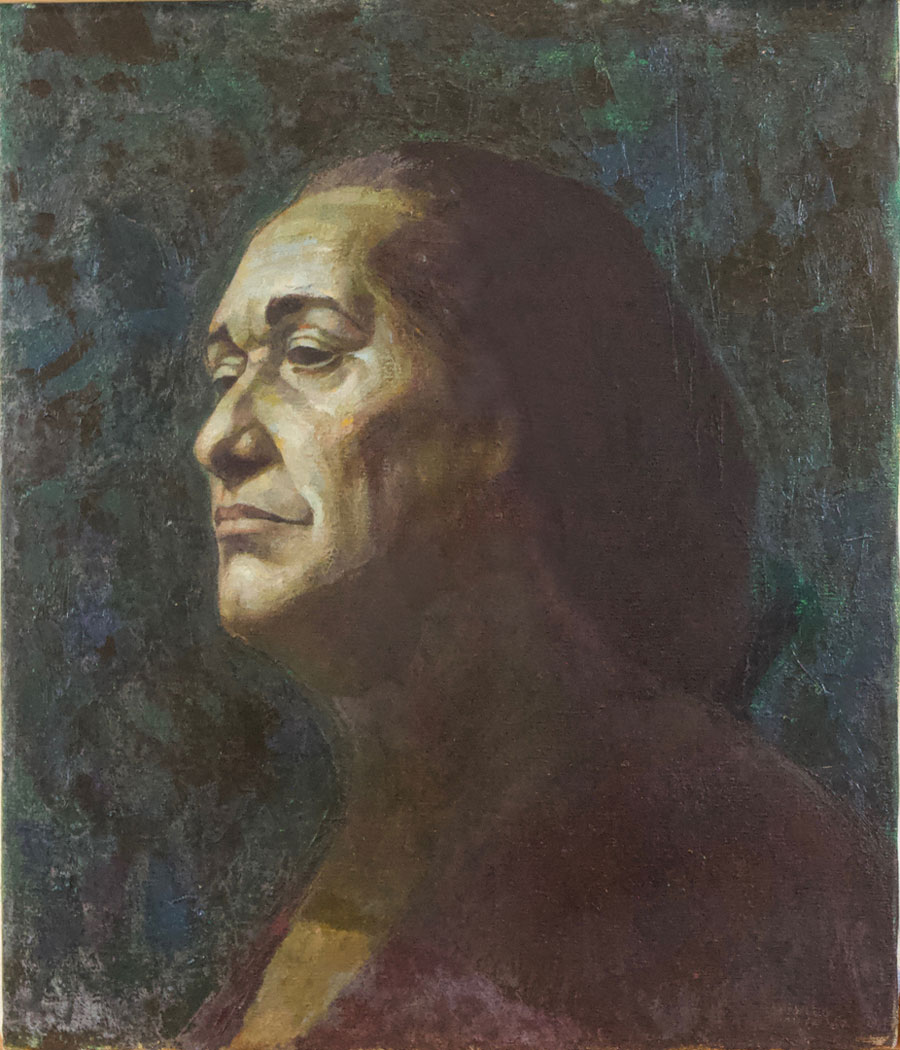

I’m so excited for the focus of my inaugural “From the Collection” article to coincide with the major Charles White (ANA 1971; NA 1974) retrospective that is traveling to several U.S. venues this year and next. You can read a review of the exhibition written by Solomon Salim Moore here. This year, as we celebrate the 100th anniversary of White’s birth, the National Academy is proud to honor this Academician by unveiling his newly conserved Diploma Portrait entitled Matriarch. Not only is this work special for its quiet elegance and beautiful, deep, jewel-like tones, but it was a unique selection for the artist to give. Rather than a likeness of himself, Matriarch is a poignant, personal depiction of—and dedication to—his great aunt Hasty Baines. White’s works often depict female figures, for the artist felt they “represent qualities that are good, real, and substantial.”1 For White, his great aunt’s life represented the very ideals that he strove to convey in his works: wisdom, courage, and beauty. In the Academy’s artist file on White, there is a copy of a letter handwritten by his wife, Frances White, penned a few months before the artist’s death. She wrote:

[… Hasty Baines] was one of 18 children born to Patience Yellowby and Frank Harris—slaves on the Yellowby Plantation (Patience was fathered by the Plantation owner) in Ridgeland, Mississippi. Charles marvels at her strength and wisdom living so many years in the heart of the deep South and still maintaining such beauty and dignity. Charles remembers her visiting his mother once in Chicago.

Every Christmas, before her death she would send us a complete, festive dinner through the US Mail to us in New York—pecans from her trees, homemade gravy, home canned vegetables, fruit cake, etc. We have cherished her letters to us when we were first married. 2

Matriarch speaks to us not only through its content, but through the act of White selecting it for the collection. This is a perfect example of how the Academy’s artist-led submission process resulted in works entering the collection before they were more broadly recognized as having institutional importance. When White submitted this work in 1973, many museums were not championing the work of African Americans. The Studio Museum in Harlem was founded just five years earlier, in 1968, and the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition (BECC) the following year. The work itself predates the establishment of these important institutions, White having painted it in 1967, and in a way adds to the weight of White’s statement in submitting it. This freedom of choice is a defining aspect of the Academy’s collection and a huge part of what makes it unique.

Paintings Conservator Kristin deGhetaldi was enlisted to examine and treat Matriarch.3 For this article, she shared with me a brief description of the work’s condition issues, her process to treat them, along with photos taken before and after. Her remarks are below:

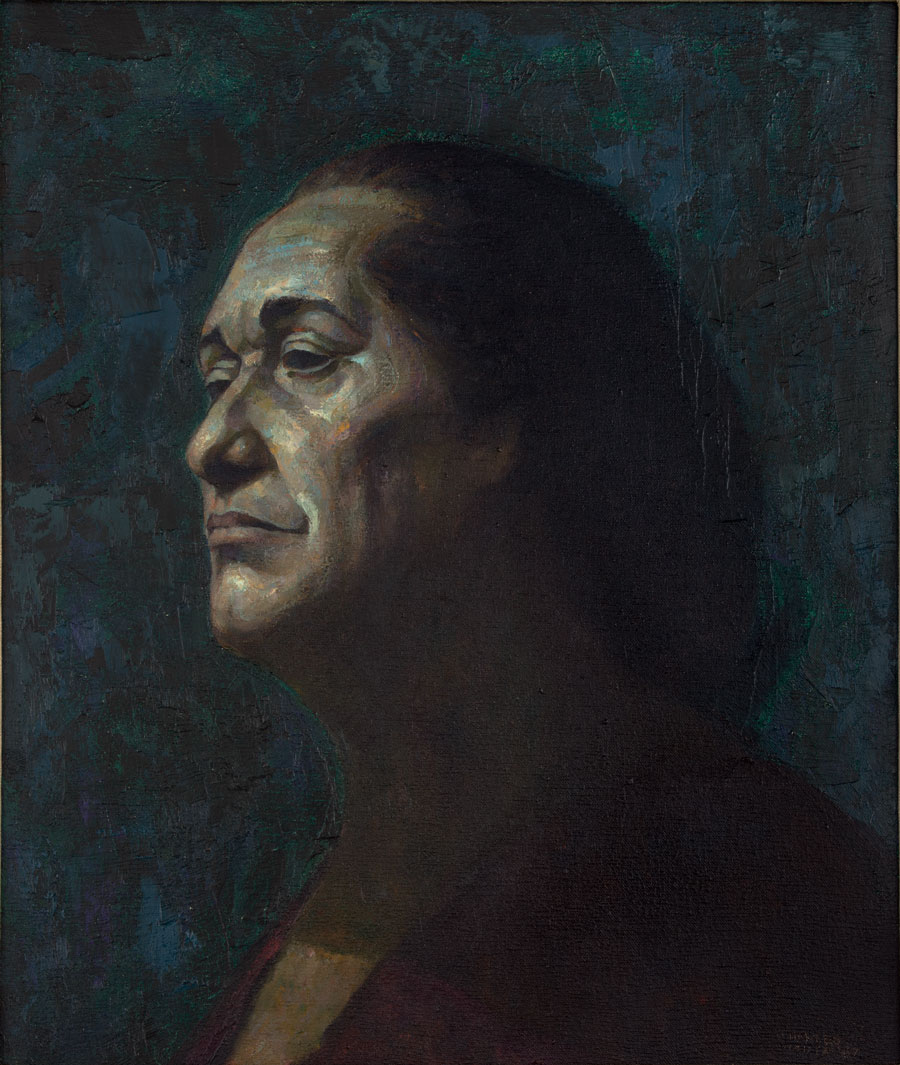

“Before conservation treatment began, examination of the painting confirmed that the surface suffered from the presence of a hazy, whitish substance typically referred to as efflorescence. This chemical phenomenon is generally caused by the migration of free fatty acids that are naturally present in the paint and is not dissimilar from the whitish haze that we occasionally encounter on chocolate candy. Fatty acids can be found in waxes, drying oils, and even egg yolk (which is the primary ingredient for the preparation of egg tempera paint); in this instance it is possible that White’s paints contained additions of wax and/or were simply “fatty” to begin with, meaning that he added a significant amount of drying oil to his pigments. While the underlying paint layers appeared to be in excellent condition, the efflorescence was obscuring White’s jewel-like palette consisting of purples, greens, and blues, and had created disfiguring patterns throughout the sitter’s hair and neck. Furthermore, if efflorescence that is rich in fatty acids is not eventually removed or reduced, it can become impossible to eliminate over time. After careful testing, it was found that this efflorescence could be safely and effectively removed using a mixture of organic solvents that did not affect the underlying paint and ground layers. As there is also a chance that additional fatty acids may migrate to the surface in the future, the painting was given a very thin layer of reversible, non-yellowing varnish in order to prevent the efflorescence from returning.”

Efflorescence before treatment.

Photo by Kristin deGhetaldi

Matriarch after treatment

For deGhetaldi’s outstanding treatment of this painting, and her revealing of the beauty in a work that was so special for White, we are all truly grateful.

While preparing this article, I came across a brief autobiography by White online that was shared by his wife Frances in 1982. One section in particular resonated so deeply with me at this time of tumult in our country and around the world, and I believe that it connects in a profound way to Matriarch and the message that White hoped to convey with this work. He recalled the contact he had with peace forces around the world during his time in the Army and other travels, particularly to the Soviet Union, and the impact these experiences had on him and his work. He wrote:

“I got a perspective that is very difficult for the average American to attain, namely the ability to see international questions as the primary concern of all peoples. It is not easy for the average American to feel pride in his own culture and at the same time be able to see the qualities it has in common with cultures apparently so different from his own, to be able to identify himself with the African people, Chinese and other Asian people. At home I had begun to reach such conclusions theoretically, but only after this concrete experience was I able to make these feelings part of my actual painting and graphic work.”

Now, when our world and humanity feel so fractured, celebrating White’s work, convictions, and ideas of inclusiveness could not come at a better time. Let us hope that the wisdom and dignity displayed in Matriarch can infect us all.

Both Matriarch and White’s Diploma Work, Mother Courage II, will be featured in the upcoming traveling exhibition of paintings from the Academy’s collection, co-organized by the National Academy and the American Federation of the Arts, and details of which will be announced on our website in the coming months.

Diana Thompson is Director of Collections and Curatorial Affairs at the National Academy of Design. In addition to organizing a major traveling exhibition of 100 paintings from the NAD’s collection that will go on tour to eight US venues beginning in March, 2019, she is also currently leading a multi-year initiative to digitize the entire permanent collection for the newly-launched NA Database. This comprehensive online educational resource will include archival materials, biographies, and video documentation pertaining to the Academy’s membership, history, and artworks.

- A quote from Charles White included in C. Gerald Fraser’s article, “Charles W. White, a Black Artist With Works in 49 Museums, Dies,” The New York Times, Saturday, October 6, 1979.

- Letter by Frances White, June 26, 1979, National Academy of Design Artist Files.

- Kristin deGhetaldi holds a BA in Chemistry (2003), an MA in Art Conservation from the Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation specializing in easel paintings (2008), and a PhD in Preservation Studies from the University of Delaware (2016). She has held internships and contract positions at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the J. Paul Getty Museum, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, and the Smithsonian American Art Museum. She has maintained a private practice since 2008 and continues to be involved with teaching art conservation and technical art history at the graduate/undergraduate level. Kristin has also been involved in a number of web-based initiatives including the Kress Technical Art History Website and MITRA (the Materials Information and Technical Resources for Artists).