With his recent receipt of the 2020 Gold Medal from the American Institute of Architects (AIA), and submission of a stellar multipart diploma work, Keenan TowerHouse, to the National Academy of Design’s permanent collection, I wanted to take the opportunity to find out more from Marlon Blackwell (NA 2018) about the submission he gave, his thoughts on the events of this tumultuous year, and where his practice is headed.

Diana Thompson: There’s no point in avoiding the most influential matters at hand today, so let’s get right to it. How has our country’s current social, political, and cultural landscape—the pandemic, our reckoning with systemic racism, and the deep social and political divides—impacted your thinking? Has this translated into your work?

Marlon Blackwell: 2020 has influenced the way I’m responding to present-day issues in what is hopefully an effective manner that moves beyond platitudes and pronouncements. My partner, Meryati Johari Blackwell, and I have been much more proactive about how we facilitate diversity within our firm, Marlon Blackwell Architects (MBA). And how we help the Fay Jones School of Architecture and Design at the University of Arkansas1 diversify their student body and provide more opportunities for students from any socioeconomic background to receive an architectural education. We are doing this through scholarship opportunities for the school, as well as internship opportunities on behalf of our firm. Regarding the pandemic, we have been actively involved in our community, fabricating and distributing PPE jointly with the university. Our firm’s work has always strived to be about forms of equity through the interface of our buildings with public spaces; now we are also beginning to think about the implications of COVID-19 through interior spatial organization in our newest projects.

The Visitor Center at Shelby Farms Park in Memphis, Tennessee, certainly displays this notion of equity conveyed through the interface of buildings with public spaces. Serving as the entry point to this immense urban park, master planned by James Corner Field Operations, the Visitor Center (and other surrounding buildings) draws upon the local architectural and agricultural vernacular and provides a space for all that feels universal in its minimalist form and palette. The result—once a vast area of wide-ranging landscapes that before had been mostly confined to regular visitors—is now open to the entire urban community. It warrants noting that Shelby Farms Park received the AIA’s 2019 Regional & Urban Design Award.

I think we’ve all recently had moments of self-reflection where we think, “What can I do to help, what can I do to be better?” How do you see the act of creating and the practice of architecture addressing these questions?

Bold, creative responses are inherently born out of listening carefully. Practicing in this way allows one to curate differing viewpoints and opinions and to hear every voice as part of the design process, and where ultimately, the most optimal solution is one where everyone feels mutual authorship. I’m imagining an architecture with core values that are essentially stable and time-tested, yet a bit wilder at its edges; contingent, embracing, with the capacity to adapt to changing time and use.

It’s hard to say when, and if, things will return to what we used to think of as normal, before the pandemic hit. What are some of the lasting impacts you see this time period having on architectural practice?

I think the whole way in which we look at the articulation of interior space is being reimagined; the materials, light, mechanical systems, air quality, and ergonomics of how we move about space—including doors, windows, and stairs, and the way those elements are engaged with by the human body. These are being rethought to minimize the transfer of contagion, whether it’s airborne or by touch through surfaces. This could have a real impact, creating an opportunity for architects to set the new standards and to join with manufacturers and contractors to help establish what the new normal can be. I do think the pandemic impacts the way we practice as well; while practice will in many ways always maintain its relational aspects, the idea of remote meetings and communication has a much greater presence and influence on us near and far. This pandemic is going to introduce new technologies in how we draw and model in real time virtually. What’s next, a virtual practice? Perhaps a more mobile practice?

This year you were awarded the AIA Gold Medal, the institute’s highest honor, which recognizes those whose work has had an enduring impact on the theory and practice of architecture. What does this mean to you? What would you like to see in future awardees?

It is the ultimate affirmation by and from my peers of the ethos that sustains us—which is that architecture can happen anywhere, at any scale, at any budget, and for anyone. It underscores the good work that is happening by small, impactful firms working outside the centers of fashion. It’s a big win for all of us in the middle… those of us from places some folks call flyover country. By recognizing the middle this way, we unite the whole country, all of us, around the cause and importance of architecture to improve everyday life.

I think what makes the Gold Medal so significant is that it recognizes architects that are from a wide range of approaches in their thinking and making; a range that demonstrates the necessary union of criticality and instrumentality and how it works to solve for present day issues and challenges for society and the built environment. This award recognizes their positive influence on the theory and practice of architecture, and it should continue to do so. I believe that awardees should have a developed architectural discourse and a strong body of built work to support it.

Some may regard the Ozarks as flyover country, but the region is undoubtedly having a moment now, both in the art and entertainment spheres. What draws you most to the Ozark region of the South? Is it something specific about the land?

What I’m drawn to has a lot to do with the natural beauty of the place—the ancient character of the Ozark Mountains and that intersection of hills and valleys that creates a landscape imbued with the order of change. While typically an impoverished area of the country, the wealth of companies like J.B. Hunt, Tyson, and Walmart have begun to elevate the region, providing greater economic opportunity and a cultural transformation centered around art, nature, architecture, and well-being. The culture here is very pragmatic and resilient with a great deal of pride in independence from tradition, and perhaps from emerging traditions as well. If you’ve ever read Ralph Waldo Emerson’s essay “Self-Reliance,” I think it captures the spirit of the Ozarks perfectly well. And as a practicing architect, what I love about the Ozarks is the fact that I can get things built here and built rather quickly.

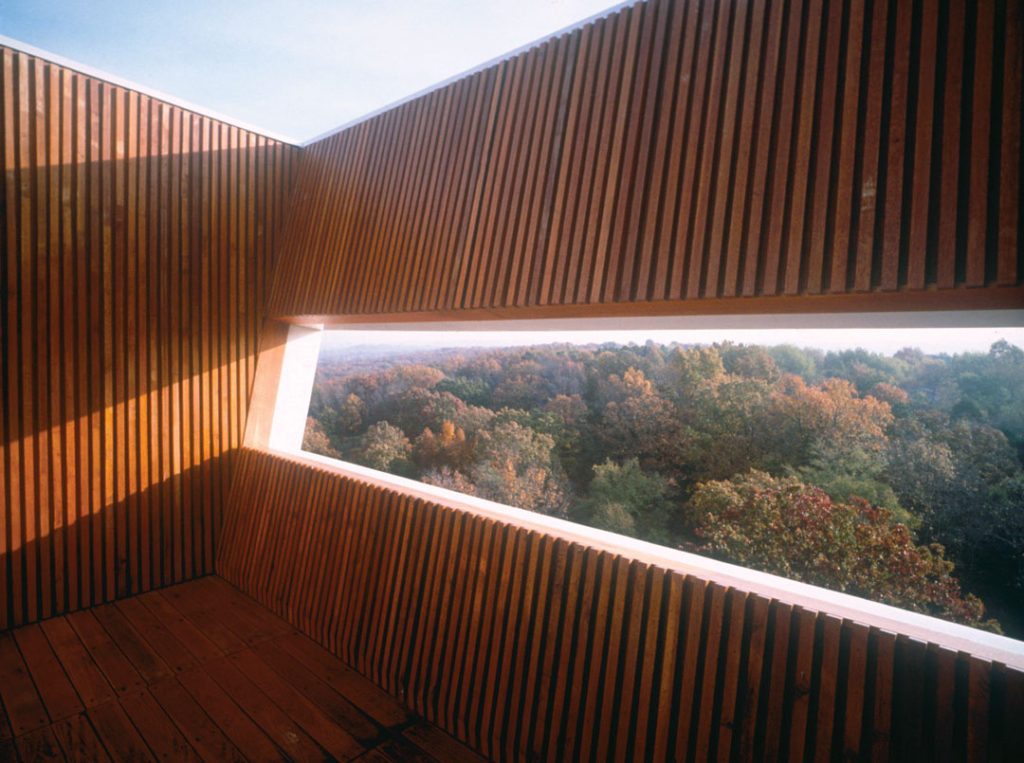

After being elected as a National Academician, you donated a work to our collection—a collection that is formed by the artist and architect National Academicians, and therefore singular among all other art collections in this country. Keenan TowerHouse in Fayetteville, Arkansas, was an early project for you and it certainly communicates with the natural beauty of the Ozark region that you mention—that intersection of hills and valleys. Keenan TowerHouse has been described as a “sanctuary.” Living during this moment in time, I find that notion comforting. What are your thoughts on that? Is that idea something you aim to create in other projects? What made you select this for our collection?

The idea of sanctuary, or perhaps refuge and prospect2, is something that is integral to our work. So much of architecture is about the act of viewing and what lies beyond. The best architecture anticipates this and sets us up to be in intimate relationships with the immensity of the world around us. Nearness in our experience of architecture demands more tactile responses. Simultaneously, we visually frame the exterior (the horizon) while allowing it to inscribe itself within the interior, to become part of the room. The Keenan TowerHouse does this beautifully, connecting us with the horizon at 360 degrees (what is beyond) and as well with the cosmos (what is above). This was the first project that was born out of years of reflection on the material, spatial, and formal nature of what I thought architecture could be. In many ways, it resists categorization and the numbing instrumentality of its place. This project really put our firm on the national stage when Robert Ivy decided to put it on the cover of the February 2001 issue of Architectural Record entitled “Out There… Architecture Outside the Centers of Fashion.” This was a pivotal moment in my career where we began as a practice to transition from the local to the national and the global.

You mentioned in an interview with Architect Magazine that you admire Thomas Eakins (ANA 1902; NA 1902) and Mary Miss (NA 2015), among other artists. Miss and Eakins are both National Academicians, one contemporary, one from the past. How do you feel about being part of a legacy that embraces such a range of different creatives? Nearly 2,400 artists and architects have been elected since our founding in 1825.

Wow, I didn’t know this. I’m honored to be a part of this legacy and the diverse range of artistic thinking and making that compiles the Academy. It’s humbling to be in the company of those I have long admired and in many instances considered heroes; true pioneers and revolutionaries. When I consider my modest and meager origins, I must say being part of the Academy makes me feel very fortunate.

One aspect that makes the National Academy of Design unique is the celebration of both art and architecture. I think this is where some of the most interesting and compelling ideas can arise from—when disciplines overlap or connect. Do you see yourself looking to other disciplines for inspiration?

I am constantly looking at other disciplines for inspiration and insight into thinking analogously, how to confront the world as its given to me, and how I might re-present that world as I find it. Art as an aesthetic experience, whether from paintings or sculpture or environmental experience, often provides a gateway into my creative thinking about material, space, light, and form. Specifically spoken word, whether poetry or music, has greatly assisted the patient and passionate search that I most often conduct inwardly, and which drives my inspiration.

This makes me think of one of your most recent projects, the Reels Administrative and Arts Building at the Thaden School in Bentonville, Arkansas. The school itself offers a unique curriculum of integrated disciplines, focuses on a collaborative and equitable experience among students and teachers, and ultimately exists as a space for education and wellness. This mirrors many of the values that you strive for in your practice. Would you share something about the inspiration for this project?

My inspiration was rooted in the material culture and vernacular typologies of Northwest Arkansas. We looked specifically at local farm groupings and linear chicken houses in the master planning of the campus. The form of Reels was really born out of a desire to create variety and dissimilarity in the classroom and building interiors; an effort to overcome the numbing instrumentality that you find in most school classroom buildings where all things, in spite of their appearances, are not equal. This is achieved by allowing the roof to pitch and roll, to rise and fall, to connect the student with both earth and sky. This desire for difference was a desire to inspire, to provide an alternative model for a new curriculum of education particular to the Thaden School. The building had to be tough, but at the same time responsive to the day-to-day needs of the students and faculty. It is clad in a custom colored box ribbed metal panel system and reinforced concrete panels with ordinary plywood ceilings. The custom green-gold metal flake color is borne from our love of the 1967 Shelby Mustang, as well as the natural grasses that are planted throughout the campus. The building is in effect the result of the intersection of what is culture-made and what is nature-made.

What are you interested in now? What are you currently working on that you’re most excited about?

I am most interested in the reductive and expressive character of profile and silhouette, as well as the tactile luminance of darkness in architecture, especially in interior space. I am excited about the development of our new monograph, Radical Practice, which comes out in 2022, and is a collection of our place-based work and inspiration images with writings and essays by a range of artists, architects, and landscape architects. We’re doing a wide range of work right now in the office including educational, health, public space, and embassy work. It’s all architecture to me, and I am so often amazed at how it has manifested into such a diverse array of building programs and types.

Diana Thompson is Director of Collections at the National Academy of Design. She is the co-curator of For America: Paintings from the National Academy of Design, a major traveling, eight-venue exhibition of 100 paintings from the Academy’s permanent collection accompanied by a richly illustrated scholarly catalogue. The show is currently being presented at the New Mexico Museum of Art, and will travel next to the Figge Art Museum, the Crocker Museum of Art, and the Oklahoma City Museum of Art. Thompson oversees a collection of nearly 8,000 works of American art and architecture, and recently began a multi-year strategic plan for the collection that focuses on care, documentation, and accessibility.

Marlon Blackwell (NA 2018), FAIA, is a practicing architect in Fayetteville, Arkansas, and the E. Fay Jones Distinguished Professor at the University of Arkansas. Blackwell is the recipient of the 2020 AIA Gold Medal, a 2019 Resident Fellow of the American Academy in Rome, and a 2014 United States Artists Ford Fellow. Work produced in his professional office, Marlon Blackwell Architects (MBA), has received significant recognition including the 2016 Cooper Hewitt National Design Award in Architecture. A monograph of Blackwell’s early work, An Architecture of the Ozarks: The Works of Marlon Blackwell, was published in 2005 and a new monograph titled Radical Practice, is releasing in 2022.

- Blackwell serves as the E. Fay Jones Chair in Architecture and a Distinguished Professor in the Fay Jones School of Architecture and Design at the University of Arkansas.

- Prospect-refuge theory was developed by Jay Appleton, an English geographer and academic, in 1975. In his book, The Experience of Landscape, he proposes that humans seek out to satisfy an innate desire when reviewing a space—to have opportunity (prospect) while being safe (refuge). This stems from evolutionary survival, where the predator must be able to see their prey without being seen.