Artists Pope.L, Catherine Sullivan, and I work together at the University of Chicago where we have each spent many hours engaging with the artwork of our students. The following conversation grows from my great respect for their thinking as I have come to know them over the past nine years. Both allow themselves to be vulnerable as they orchestrate with affection and humility encounters with others in search of their subjects. I am moved by their bravery. In contrast to their training in theater, mine was focused on visual arts. This contrast, like dye added to cells in a petri dish, makes visible the ways in which our formative experiences influence the contours of our thinking.

My own work is heavily influenced by psychoanalytic theory and practice, in which I find openings to understand how meaning accumulates in flexible layers. I wondered if theater methodology provides a similar architecture for making sense of the complexity of human being. Perhaps all three of us are engaged in an effort to build a shared infrastructure that is in contrast to the rigidity of propaganda and our current polarized political situation.

Jessica Stockholder: I often think about your work and am struck by how your theater backgrounds seem to be of huge influence. I wonder if there might be parallels between theater training and the theory and practice of psychoanalysis, as in both cases meaning arises through interaction with others. Also, in both, the process gives rise, at least in part, to the subject. How did you each get started in theater?

Pope.L: I began in art performance but have always been interested in theater. Both psychoanalysis and theater/art performance use talking as a means to get at stuff. However, in performance art and theater there can be an antagonism between talking and doing. Some believe language gets in the way, especially in performance art, for example, à la George Brecht. My teachers, as a whole, were not purists; they did not privilege language over action. Some visual artists, friends, and colleagues feel theater is too artificial, too old fashioned, too slow and pretentious. Maybe it isn’t that theater is too talky, but that it is too dependent on pretending. My performance art teachers built their practices and teaching styles from direct observation, working with other artists, and trial and error—and developed through self-guided processes, while my theater mentors typically had some sort of formal training. Either way, both used whatever approaches and techniques they felt necessary to get their subject matter across; therefore, the training I received may have, at times, felt higgly piggly.

Catherine Sullivan: In places where you might expect strict training, it’s also higgly piggly. When I look back on the conservatory I went to, where you might expect more consistent pedagogy, it was hodgepodge. The theater department was not in any way connected to the interests of the art department. When I was there, it was a strict conservatory model, geared toward American repertory theater, where you had a certain repertoire and canon that you were expected to be familiar with. But the acting training was all over the place. It was like Tai Chi Chuan combined with jazz dance, combined with mask theater work, combined with some theories about acting that were developed in the 1950s. So, while it was strict and intensive, there was no coherent method, and you taught yourself how to bring it together.

Stockholder: In some ways that sounds parallel to my experience of visual art. We were all educated and developed our work in context of a time in which hybridity was assumed.

Sullivan: While my training was hodgepodge, preferences and expectations still persisted, and they were in some cases culturally predicated, and in others they were more subjective. There was hybridity, but there was also a way of moving, a way of speaking, a certain kind of presence that was valued.

Pope.L: Among my theater cohort, a number complained that their options in theater or film were too limiting, so they jumped ship into experimental theater or art performance to gain more control of who they wanted to be artistically and what they wanted to make.

Stockholder: It’s true in both worlds that you can’t escape your identity as an artist/author.

Pope.L: It’s not just personal identity that shapes one’s success in a field, but the limitations of the field, the market, and the time period in which one is working.

Sullivan: There were certain roles that I was always up for, but that I had no feeling for or interest in. It’s challenging to confront the semiotics of your own presence and how those codes play into the world. I had always wished that this was made more explicit in my training, so that we could learn to more consciously deploy these codes. That would have given us a lot more agency. It’s hard to productively address that issue of commodity and where it intersects with artistic work.

Stockholder: Working with our students, we also struggle around how to make awareness of commerce useful to them as they develop their work.

Shifting the conversation a little, I’m wondering if the psychoanalytic method has something in common with theater methodology? I appreciate in psychoanalysis that the analyst leaves themselves more or less blank, and the analysand has an opportunity to become aware of their own imaginings and projections. The complexity involved in making sense of one’s subjectivity necessitates understanding meaning as fluid and context dependent. That’s important to me in my own work, and it also makes sense of the process in which we engage with students in critiques. We watch an accumulation of different people’s thinking map together and form a cloud of interrelated thoughts. Rarely does anyone walk away and think, “Ah, yes, now I get it. Now I know the right answer.”

I work with materials and ‘things,’ all of which have in one way or another passed through human hands; in this way, I work with other people at a remove. You both work with people more closely, and I wonder if the theater processes that you use in your work yield meaning in a similar way?

Sullivan: As a young student of acting, the exercises we were asked to do involved a lot of sense memory work and emotional memory work, but they always corresponded to the characters we had to portray. There were some good processes which helped us find emotions first through physical sensation. Instead of trying to manifest sadness, for example, we would go into a guided meditation recalling physical circumstances that made us sad, because those environmental sensations would trigger the emotions.

I always found that to be useful. I had teachers who were skilled in setting up the exercises, and classrooms that could sustain varying degrees of emotion, sometimes in extremes. When I started bringing my own ensembles together, that was a normal way of working; I realize now how lucky I was to learn from people who knew how to do this safely. And because we always had the corresponding theatrical material to apply it to, it felt concrete.

Stockholder: Do you take something from that theater experience to your work now? You still work with people, you hire actors, but I believe that most of what you make now is video. It doesn’t have the immediacy of theater; you’ve taken the actor’s acting and edited it. But there must be something you value about the process of working with those people.

Sullivan: Yeah. On the one hand, there’s the social dimension; it’s affirming to be in a space that can hold emotional feeling on a lot of different levels. In terms of the process, there are some people who, when asked to convey emotion, insist on their own methods because it’s a private thing for them. There are others who actually enjoy letting someone else guide that process. I try to respect both approaches; everybody’s going to work differently. More and more I see the value of trainings that create contexts for people to hold space for one another and where people can feel different things together. But these environments are delicate and require structure.

Pope.L: I almost never know what I am doing when I am directing. When I first started teaching some directing, I’d say to my classes, “Directing is not only about telling people what to do.” Also, I’d say: “Directors are not therapists.” You select a performer because of their abilities, but also because they’ll be able take care of their psychic selves. You also want rehearsals, especially early on, to be protected spaces. At the same time, if they’re too protected, you can’t go deep into the questions you’re after. Performance art and theater are both goal-oriented, even if their techniques are sometimes different. A director takes responsibility not just for leading, but also for failing. The director says: “The dot on the paper is here, not there, and for the next few minutes we’re going to believe that, okay?”

Stockholder: You’re telling me that as a director, you are orchestrating these other people and asking them to collaborate with you to bring the content forward?

Pope.L: Yeah. I tell folks: “The project is a shared dream. We all have a part, but there is one goal. I do not know everything about the dream; how could I? But I have some ideas about how to get to our goal. What do you think?” A director’s job is not just to point, but to point in an interesting way.

Sullivan: I’ve always found that people appreciate the fact that you’re struggling to figure it out. That’s where trust is established. The situations that I have not trusted and seen other people not trust are ones where it appears someone hasn’t prepared, which is different from not knowing, and different from experimentation, where you can be transparent about what it is you’re trying to work on. If people feel like they understand where to apply their craft and knowledge, there can be a lot of experimentation.

Pope.L: A teacher of mine once said: “It needs to be bad before it is good.” So, I know from the get-go that we are all entering the process of making by stumbling. Likewise, in counseling, when things are clumsy, confusing, and gnarly is when the payoff is greatest.

Stockholder: Neither of you call yourself social practice artists, do you?

Pope.L: No, but…

Sullivan: No.

Stockholder: Social practice art departments are relatively new. Part of their popularity grows from the hope that art will fix the world. Sometimes artists move into social work territory without any social work training. It is clear to me that you both care a lot about the training that you’ve received, and about your teaching.

Pope.L: I’ve made some things that might be considered in the social practice vein, like The Black Factory and Flint Water. Both works were made to interact with, provoke, and serve communities. It is key that artists want to interact more with their communities. There is no more important material for humans than humans. In addition, where one works influences how one works. With whom you work does something similar. I have worked in shelters, poetry venues, dance venues, the street—that education frames and questions the work. Finally, we have to keep in mind that social practice is a relatively young practice and so missteps, arrogance, mistakes, and stumbling have to happen for it to mature—if mature is even what it wants to do.

Sullivan: There’s also a problematic but interesting issue of social engineering cutting across this work. I’m thinking of people like Neva Boyd, a sociologist who worked in a settlement house here in Chicago in the 1920s and 1930s. She developed exercises and games that would help immigrant families and children integrate. These exercises were developed to address a social condition, but also evolved as artistic techniques that had a huge impact on the practice of theater.

Pope.L: The market lags regarding what to do with this work. The closest they’ve gotten so far, at least most recently, are the self-involved gallery pieces by Tino Sehgal.

Stockholder: In Tino Sehgal’s work it’s clear where the line is between his work and the audience.

Pope.L: Yes, and what is clarity when you are dealing with bodies? The spacing between bodies in Sehgal’s work tends to be flat and controlled. In terms of feel, however, I think he wants a counter-effect, for example, intimacy, such as when two people talk. This is supposed to put the body separation and the intimate chat in some sort of tension. This is unlike, for example, the Living Theater, who are much messier. In a way, maybe they’re after the same goal: a spillover into something else. Revolution for the Living Theater, for Sehgal…?

Stockholder: One lovely thing about the creation of art space is that it can hold offensive, upsetting, and antisocial content and behavior that we don’t have bandwidth to engage with elsewhere. It’s like going into an analytic session, where you can tell your analyst anything and the agreement is that they’re not going to call the cops because your fantasy life isn’t socially acceptable.

How does that strike both of you? If you erase the crisp line between your work and the rest of our world, then you have different kinds of responsibilities towards the people you’re working with. I’m curious how each of you feel about the intersection of an art form that allows for insanity, anger, and upset as distinct from being in a homeless shelter with people who aren’t artists?

Sullivan: There is some great work by a company called the Los Angeles Poverty Department whose early works were written and performed by people who lived or had lived on Skid Row. Also, I worked in 2014 with a theater company in Poland, Opera Buffa, whose members are living with schizophrenia. Both are companies that distinguish themselves as artists working with specific kinds of knowledge. In both cases, the companies don’t think of their work as social practice, but as art, and it can at times be disturbing.

My view of the distinction you are making, Jessica, is that in art there is often a mistaken premium put on what is considered authentic, and there are perennial contestations between artifice and verisimilitude. For example, I’ll often get into a discussion with students making performance work who do not want to be seen as acting. Maybe the presence of acting sets up the possibility for bad acting, which can create a shared sense of failure. We all want to avoid this, and so I think people get nervous when they are in the presence of acting until and unless it’s really good. When it is, we celebrate actors. It’s interesting that there’s this anxiety and mistrust around artifice, and often the solution is to dispense with it from the get-go.

Pope.L: Little kids get it from the get-go. When they become the tiger, they are the tiger. College students are suspicious of being the tiger. They say, “It has to be meta. Something beyond just being, something more clever.” I say to them, “Your meta is getting in the way of your tiger.” My students do not trust public pretending.

Sullivan: There’s something that can be strange for people about othering yourself. When you’re performing in a role, you have to create this space of otherness that’s not you. Same thing when you are executing someone else’s instructions for your behavior. There’s a lot of resistance to what’s perceived as a loss of agency. That’s why many people are suspicious of actors. It’s like, “Who would want to do that? Who would want to surrender their agency and shift the framing of their existence over to another person?”

Stockholder: That word, othering, is the focus of a lot of political upset right now. I’m thinking about the question of whether or not it’s okay for Dana Schutz (NA 2010) to make a picture of Emmett Till.

Pope.L: In the case of Schutz, I think it’s interesting for her to attempt to paint key moments in Black tragedy. Why not? She should engage in our shared American history. But is she engaging as a tourist, or as a family member? She is entering late into a dialogue, a pain that long proceeds her, so if she is entering as a family member, what is her role? For years, I did a ton of studio visits. It was not unusual that a white student would say to me, late into the visit: “I have something to show you.” Nine times out of 10 it was something about race, and I would always ask: “Have you shown this to your professors?” Nine times out of 10, the answer was no. In the end, I always told them the same thing: “You have the right to talk about our shared American culture, even if your contribution is half-baked, confused, and possibly racist. I mean, what do you expect? How do you think white folks have been trained in this country, even the good ones? It will take time and courage to do this work with any level of depth and integrity, so buckle up.

Stockholder: Not too many people are saying that.

Pope.L: Too bad, but what else was I going to say, “Don’t show it?”

Sullivan: I wonder, though, if in this moment we’re actually going to cultivate structures that bring these attempts out and create a place for people to speak about them, or if they’ll continue to remain hidden. What’s the ecology that allows this work to be discussed constructively? Are people implicated by it in a way that they don’t like, and if they are, what do we do about that? I feel like we have breach and crisis, but we need more developed structures to redress and integrate what comes up.

Pope.L: True, true. If the process is doing what it’s supposed to do it won’t always be a polite, comfortable, straight-forward woo-ha. “It’s got to be bad before it’s good.” As per therapy, when you finally wrest a bit of light from the murk, it’s blinding, and most times there’s no rainbow nearby to rescue you. So you have to live in the discomfort of not knowing. That sitting in not knowing is key to figuring things out.

Sullivan: I agree. Just being in a room with a particular group of people who are together regularly to speak about these topics would at least create a way of working through certain conversations, and to give a structure for students to feel safer. Without that practice, it’s difficult.

Pope.L: I agree. And I like the word practice in describing what that process might be about.

Stockholder: Maybe akin to psychoanalytic practice. One of art’s strengths is that it doesn’t always go where you want it to. I often say to students, “The art is not you; it has to exist without you in the end.” And, every time I say that, I wonder what you would say, Pope.L, because that’s clearly not the whole truth. Everything we make is freighted with our authorship and identity, and how we’re received by the world impacts whether it’s received at all. Our color, our gender, our class all impact the meaning of the work. So perhaps my proposal is an ambition or an ideal. Even so, I’m interested in how art is an effort to communicate beyond ourselves. As you both work with time, people, and occurrence, I’m imagining that you think about that line between your person and the work a little differently.

Pope.L: I accept your conundrum as simply the natural byproduct of the process we call making something. Yes, the thing-made is separate from its maker, and the maker is intertwined with the made. I agree, but then what? This is interesting in art, but in other fields it is not so important. Who knows who made the aspirin, or the wheel, or the pop-up sink plunger?

Stockholder: I asked a question about the nature of separation between oneself, the artist, and the world. You went right away to training, which is interesting.

Pope.L: Training protects one from the world. It’s a discipline. At the same time, it is a form of propaganda. To a certain extent, ownership of ideas and originality is thought about differently in art than other fields.

Stockholder: Thinking about our own work, Pope.L, yours often intersects your identity in a transparent way. I also appreciate that the work doesn’t announce your identity. Catherine, your work doesn’t do that in a way that’s obvious to me as a viewer. I would say the same is true of my work. Given the time and place we live in, one might say that you and I, Catherine, are privileged to not be obliged to have the work announce our identity. I think African American artists who make work that doesn’t announce identity tend not to get a lot of attention; not until they’re really old.

Pope.L: Jessica, I’m not sure how transparent my work is identity-wise… However, the idea of not having to announce my identity as a thought experiment is… interesting. I wonder what would happen if I were to seriously put that idea in play?

Stockholder: I did that without thinking about it. I understand that there are conventionally masculine and feminine ways of making, and I’m aware of those meaning tags being applied to the work. Even so, I feel that the things I make are in dialogue with all kinds of people’s work. Like you say, there are losses. I never wanted to be known as a woman artist. People like to discuss my use of domestic objects, and as soon as that question is asked of me, I know that they’re going down the woman path, proposing that somehow domesticity is a woman’s thing. That’s a pile of crap. We all live in domestic situations. I won’t go there.

Pope.L: It’s sometimes difficult dealing with folks calling me out about my loyalty to Blackness, but I feel it’s a necessary dialogue, especially for young Black artists finding their way through the color noise. It’s my fault, partly, that I draw this fire, because I intentionally push the boundaries of Black art so it can grow and be further challenged. I found clarity in the realization that though my skin color might be darker, my interests are wide. Yet, to a great extent, my life and values have been determined by skin-color privilege. That is how this country’s politics are organized. I can’t deny that. So how do I enter the conversation about loyalty to Blackness versus loyalty to self? It took a while to realize that I did not have to choose. Instead, I could refract the tension in that conflict. I can be a multitude. And I am lucky that I can make that choice. Many Black artists before me did not have that option.

Stockholder: Have you made your peace with that, Catherine?

Pope.L: You’re a multitude, huh?

Sullivan: Yeah, I’m a multitude, totally. No, like everyone else, I want as much mobility as possible.

Stockholder: That’s not true of everyone else. That might be true of the three of us.

Sullivan: There are definitely advantages to being able to work within and outside your identity however you choose, given the particular pieces that you want to make. Also, I work primarily in ensemble-based media, where the question of authorship and identity is more prismatic and decentralized. I’ve also tried to let myself be in the work by not correcting certain kinds of mistakes. Sometimes these mistakes have to do with misreading, where I recognize a bias or mindset that might be shaped by class, gender, or race and I give it a place in the work.

Pope.L: The “What can be Black art?” question is the same question art has been asking since art began, meaning: “What is possible in art?” Maybe that’s the only question, because based on the answer, it will engage all sorts of encounters. And race? Well, maybe that’s just another question within the question.

Sullivan: George Lewis calls that the one-drop rule of jazz, meaning that one drop obligates you to a whole set of genres and practices that are racially defined.

Pope.L: To be so colorful…

Sullivan: Yes.

Pope.L: I have my obligations and you have yours! That statement seems, on its face, to be pretty indefensible, yes? But isn’t it also true that my obligations, to an extent, overlap yours? In the United States, it seems we focus on individuality to the detriment of our collectivity except, as expressed, in current corporate statements like: “We are all in this together.” Well, what if we are? What does that mean? Aren’t we all worried together? Aren’t we all raced together? Aren’t we all dying together?

Stockholder: Earlier in this conversation, you told us that you tell your students, “Yes, you can do this.”

Pope.L: Yeah? I did? Well, I also tell them, “If you want to be able to do whatever you want, you’re going to pay for it.” Choice is not free.

Sullivan: Or, that they will have to account for it in some way.

Pope.L: When you make people uncomfortable, it’s their right to say, “Who do you think you are to make me feel uncomfortable?”

Stockholder: The woman part is one thing. I also notice that being a white person, the race part doesn’t come at me very often. But the woman part of things has come at me over the years, especially when I was a young person, and people told me that women really couldn’t be artists. I heard that on many occasions.

Pope.L: They wouldn’t say it direct, right?

Stockholder: Actually, they would. I was at the Camden School of Art in London one year, and a teacher there told me, “Women can’t be artists,” and, “There are no good women artists.” And at Yale, a faculty member told me that women couldn’t have kids and be artists.

Pope.L: Hmm. Well, that’s shitty, humorous, and tragic. I’ve had my share of that kind of story. People will say anything. I say fuck ‘em.

Sullivan: Directors in theater and cinema have been and still are mostly men, and for some actors, a female director simply frustrates a set of dynamics they trust and rely on given the history of the medium. It messes with their schtick.

Stockholder: I have one last question. Another interesting aspect of psychoanalysis is the question of judgment. One doesn’t engage psychoanalysis to reach a judgment; it’s rather an unfolding that yields understanding and sometimes enables choice. If psychoanalysis was brought to bear more often, with its emphasis on unpacking, understanding, and acknowledging what’s there, rather than arriving at rigid judgments, the world would be a better place. So, I wonder how you each understand the question of judgment inside of your work?

Sullivan: I’m very interested in people’s basis for judgments. Why do you want to watch some people and avert your gaze from others? What is that about? What is the nature of the transmission of charisma? I guess I’m trying to distinguish between judgments and conclusions. If you’re in the process of judging something, it doesn’t mean you’re coming to a conclusion and therefore the process stops. Or can you be in a state of judgment that reveals other kinds of attractions or interests?

Stockholder: And are the judgements you make of your own work fluid? Or do they shift over time?

Sullivan: Sometimes I go back and recut works. That’s one of the great things about film and video, I can do that. That’s also why I have always liked theater. Although you may not want to change things in a performance from night to night, you can.

Pope.L: What is this thing we seek to make? Is it even a thing? Whatever it be, it is always a broken thing. And the wind blows through its cracks bringing along with it time, pain, loneliness, celebration, triumph, and conversation.

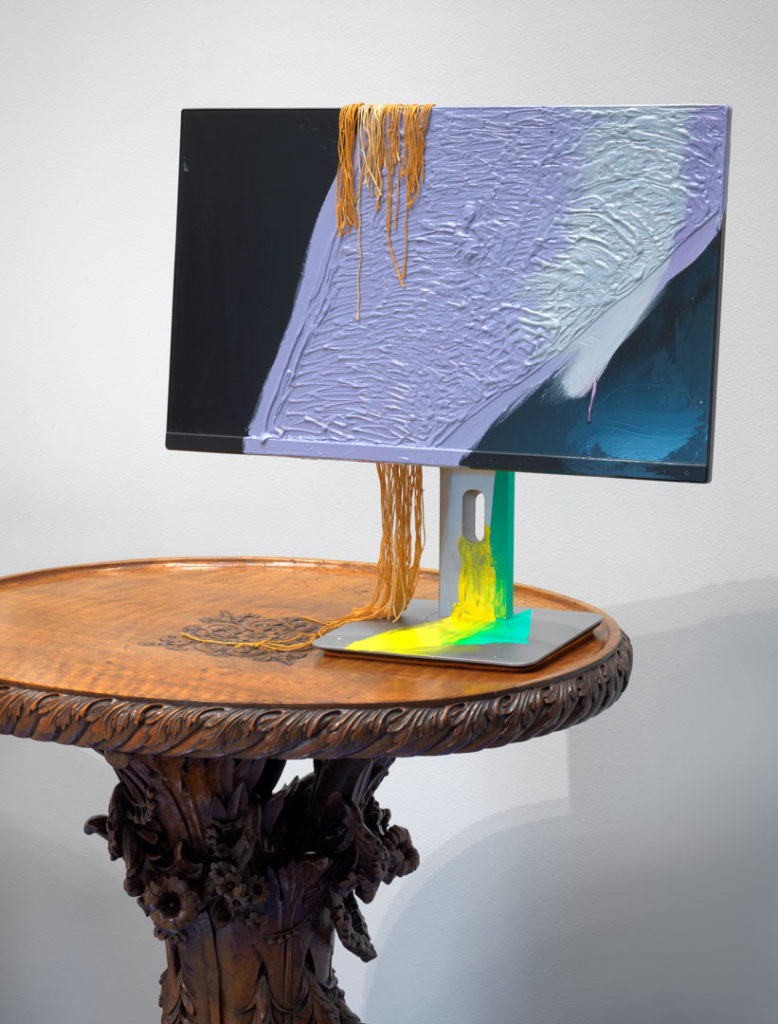

Jessica Stockholder (NA 2011) was born in 1959 in Seattle, Washington, raised in Vancouver, Canada, and currently lives in Chicago where she teaches at the University of Chicago. Her work is represented in the permanent collections of numerous museums including the Art Institute of Chicago; the British Museum, London; the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam; and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

Drawing attention to ordinary everyday materials, Stockholder engages the sensuality and pleasure evoked by color and formal order in an effort to call attention to the edges of understanding. She orchestrates an intersection of pictorial and physical space, probing how meaning derives from physicality.

Pope.L (b. 1955, in Newark, New Jersey) is a Chicago-based visual and performance-theater artist and educator who makes culture out of contraries. Recent solo exhibitions include member: Pope.L 1978 – 2001 at the Museum of Modern Art and Choir at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York.

Trained as an actor and visual artist, Catherine Sullivan has presented her film installations, theater works, and collaborations nationally and internationally since the early 2000s. Performers in her film and theater works cope with written texts, gestural and choreographic regimes, stylistic economies, and conceptual orthodoxies animating contestations and unfinished business drawn from the locations where she shoots. She was born in Los Angeles and currently lives in Chicago where she is an Associate Professor in the Department of Visual Arts at the University of Chicago.

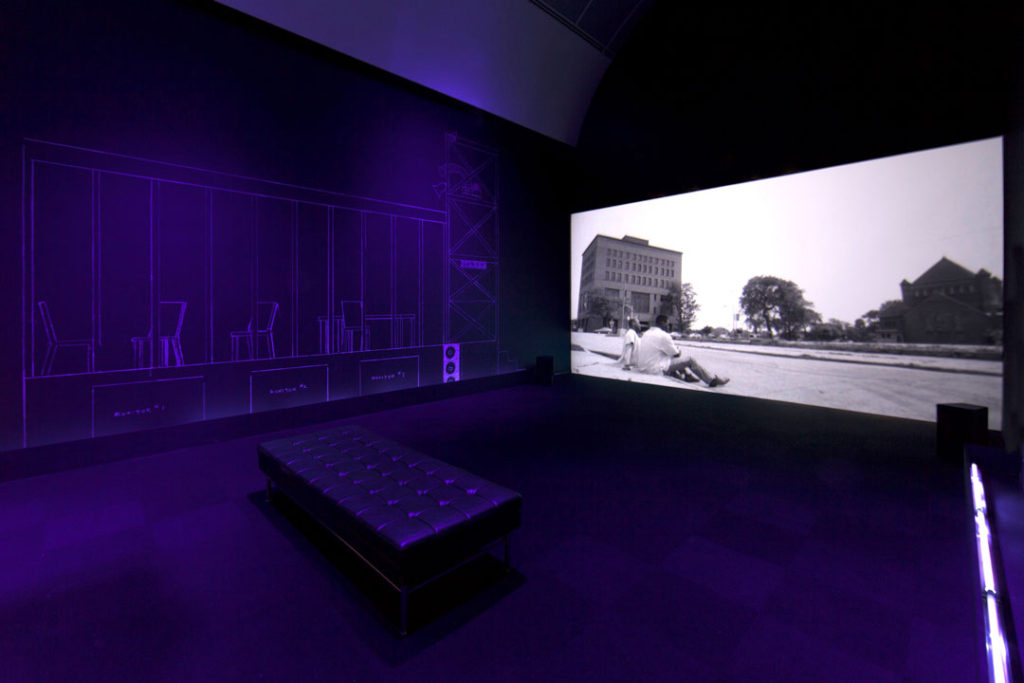

Header image: Catherine Sullivan, installation view of The Startled Faction, 2018. Digital video, color/sound, 35 mins. Metro Pictures, New York