This past January, I was lucky enough to be awarded an artist’s residency in Southern India. I was in Fort Kochi (formerly known as Cochin), in a 400-year-old spice warehouse called Pepper House, right on the Bay of Kochi in Kerala. The town is rather relaxed and unhurried—at least for India—due to its location on a peninsula away from mainland traffic; the vibe in the South, in general, is very, well, Southern, and most people aren’t in a rush. For the most part, Keralans are literate and kind, and there is relatively little tension between religious groups, with a polyglot population of Hindus, Muslims, Christians, and even historically, Jews, though now there is barely enough of them left to hold services in the lovely 16th-century synagogue in what’s known as Jew Town. There is a long tradition of progressive politics in this state, and the current government is an elected Communist coalition that is often in opposition to the central government’s Hindu-first Bharatiya Janata Party leadership.

Pepper House Residency is run by wonderful folks from the Kochi Biennale Foundation, which is better known for mounting the Kochi-Muziris Biennale, the only art biannual in India. I participated in the 2016 edition, and it was amazing—uncommercial, full of artists whose work was new to me, and held together with the equivalent of chewing gum and wire: what’s known in India as jugaad, or jerry-rigged.

Since I stayed in Kochi for several weeks in 2016, I had a pretty good idea of what the residency might be like. First, I knew that it can be unwise to have a “plan” for being in India. Things often don’t quite work out exactly as expected, which is a good thing. It is a great lesson in patience, checking one’s privilege and accepting that American willpower has limits.

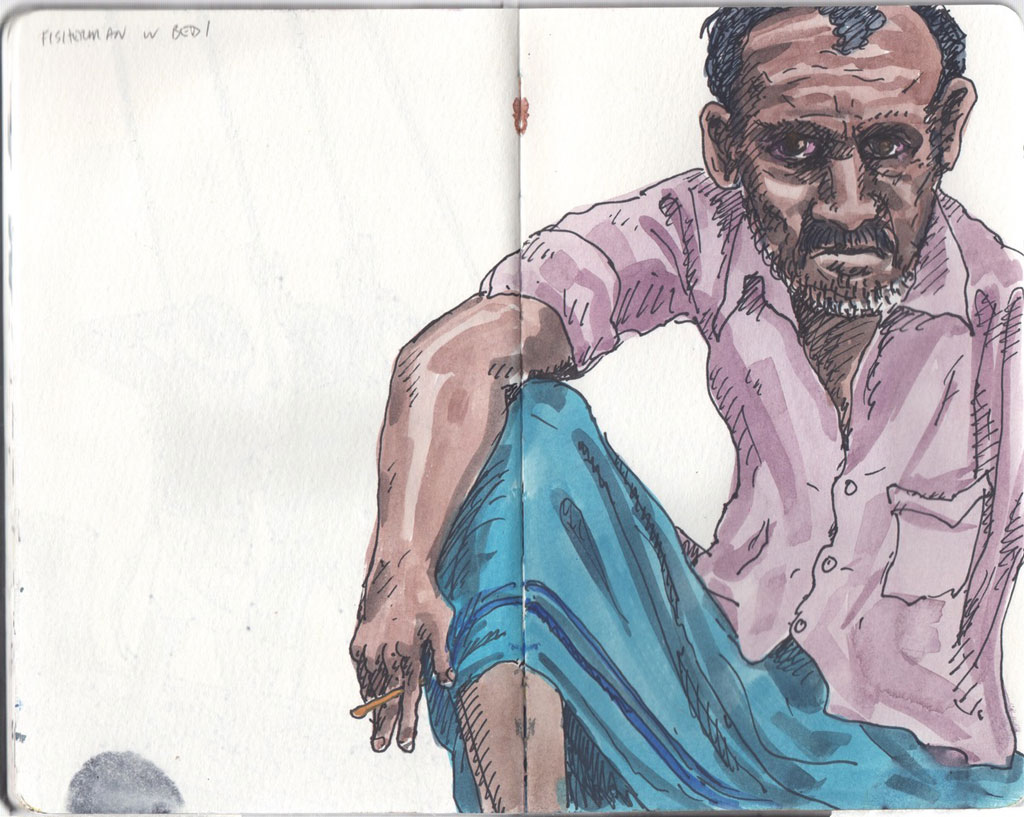

I came with a vague idea of what I might do. I would sketch the people I met—always a great way of interacting with folks—and I brought canvas pads and oil paints in my luggage and planned to haul the same out, avoiding the need for shipping and its heartbreak. I did write up a proposal, mostly for the hope in getting a grant for airfare from the university where I teach. There is a revered mural tradition in Kerala, still being practiced and reinvented today, and I wanted to talk to local artists about the color theory they utilize—the cultural and material mix.

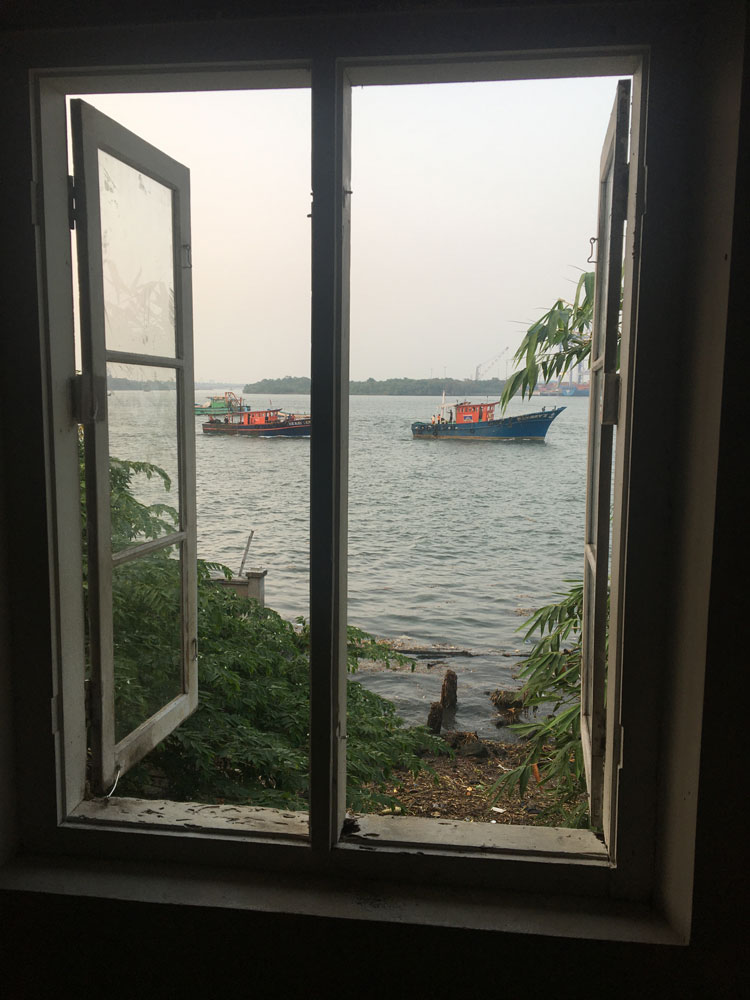

When I first arrived at the bare, sweltering second-floor studio, I opened all the old windows and looked over the bay. Far off, there is a large industrial container port, and an amazing collection of boats is running back and forth in the middle: there are small pirogues with men casting nets, huge dredge ships, container ships, tourist launches, and most of all, hundreds of midsized fishing boats with crews of six to eight men. These boats are painted in highly saturated color schemes, many of which are a deep ultramarine blue and scarlet.

Once I started painting, set up by the window to try and catch a breeze, I kept finding myself watching these boats. I started a log, noting the color schemes and their names: Aaratu, Samooham, St. Joseph, Air India, Keertheyam, Infant Jesus, Al-Rahman…

Within a few days, all the abstract paintings I had started reduced to the two colors I kept seeing—the blues and scarlets of these boats. Surely, this was a rather stupid idea; what about my research into the muralists’ color theory? But I couldn’t help it. I surrendered to this mandate, finding the limitation both focusing and strangely specific to being in India. It seemed like a fine plan dropped in my lap, literally coming to me every day through the windows.

I started wondering about the boatmen’s choice of these colors. Was it significant, and if so, of what? Many boat names were rather religious-sounding, and I was told the boat workers are often Catholics from neighboring Tamil Nadu. Was there any spiritual connection to the colors?

A few weeks into my stay, I enlisted Fahad from the Biennale Foundation, and we sped off on his motorbike to the Kochangadi neighborhood, where he knew of a boatyard. A small alley leads off the main street to the harborside, where these large ships are pulled out of the water on half-submerged train rails by a huge winch. Once in dry dock, they are scraped down and repainted.

We found a suitable informant and posed a few questions to him: “Who decides about the colors? Do they hold any significance, or is it just a consensus fashion?” After looking a bit confused about why we would ask him about this (“He is an artist,” Farhad explained. “He’s just curious.”), the boat worker revealed that it was a simple state government mandate: Any fishing boat of this class registered in the state of Kerala must use blue and crimson. Customs patrols can then tell who is local, who is from Tamil Nadu (green and white), and who is from the Maldives (all white). It’s that simple. No further significance.

Was I disappointed with this information? There was no grand cultural color theory in effect (unlike the muralists’ five-color Panchavarna tradition, which I had totally neglected to investigate). Really, it’s just government bureaucracy setting this out?

Actually, this mundane edict began to resonate with me. I liked this functioning of color theory in the real world. I appreciated the way a rather non-exotic aspect of India found its way into my work and rendered it specific to being there, without the dewy-eyed Orientalism that the West can put on a place like India. I liked the way it literally floated into my view and without too much projection. It was observational and abstract in equal parts.

I worked on these paintings for a month, with limited colors and time frame, while I was at the residency. Once I came home to New York, I created one large painting using this framework, then put it to bed. Now I’m looking into other—often arbitrary—real-world color systems and seeing what else might control my choices. I’m thinking a lot about controls as we accept the state-mandated COVID-19 protocols. These days, questions of the benefit and dangers of authority are in high relief.

Tom Burckhardt (NA 2016) was born in New York City in 1964 and has spent his life there. He graduated with a BFA in painting from SUNY Purchase in 1986 and attended the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture that same year. He has been exhibiting since 1992 at New York City galleries such as Tibor de Nagy Gallery, Pierogi Gallery, and Caren Golden Fine Art; as well as at Gregory Lind Gallery in San Francisco. His most recent solo show was Psychodiagnostik. Burckhardt has been an artist-in-residence at Pepper House and Yaddo. He currently teaches part-time at SUNY Purchase.

Header image: oil on linen, installation in Tom Burckhardt’s studio at Pepper House Residency, photo by Swanoop John